Sources Sunday: Thomas More’s History of King Richard III

See series introduction, here.

***

Today, I’d like to introduce briefly one of the earlier secondary sources about Richard III, a text written by Thomas More called The History of King Richard III. No matter how you feel about Richard, it’s a cracking read, and the late historian Richard Marius called it “the finest thing he ever wrote.” Even Ricardian biographer Paul Murray Kendall called the work an expression of More’s “stunning vitality.” Here are some things to keep in mind when reading this work.

***

This got really long, so I’ll limit myself to these introductory remarks this week and start talking about specific citations next time.

***

The source itself

- More worked on this text between 1513 and 1518 in Latin and English simultaneously, and never finished it. His English narrative stops at the beginning of Buckingham’s rebellion; his Latin narrative, somewhat earlier, at Richard’s coronation.

- Modern textual scholars believe that More composed the Latin and English versions of the text separately, transferring bits and pieces between them, so that neither text by itself is considered fully authoritative.

- No original of More’s text in his own handwriting (any so-called holograph) survives either in Latin or in English.

- The text was not published in More’s lifetime, possibly because he became too busy to finish it; or because he realized that the matters treated in the text involved too many people who were still alive, so that the appearance of the work would create political problems for him.

- No English manuscript sources survive; several Latin manuscript sources survive, but these are reworkings of the original holograph based on copies that themselves have disappeared in the meantime. The most well-known of the surviving Latin manuscripts — all of which differ — are held at Paris in the Bibliothèque nationale (MS fr. 4996 [Ancien fonds]), and at London in the College of Arms (MS Arundel 43) and the British Library (MS Harley 902). Here’s an excellent technical summary of the transmission of the texts with diagrams. Now considered to provide most authoritative Latin version, the Paris manuscript was rediscovered, entirely by accident, only in the twentieth century, by More scholar Daniel Kinney.

- The “critical edition” of the texts — the definitive version scholars consider closest to the original, which should be used by all researchers — is The Complete Works of St. Thomas More, 15 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963-97).

- Most modern versions of the text produced for general readers or students are emended on the basis of the 1557 London edition: William Rastell, ed., The workes of Sir Thomas More Knyght […]. This was not the first English printing of the text, but it has long been considered the most authoritative as it seems to have been typeset from a no-longer-extant holograph. (Rastell was More’s nephew.)

***

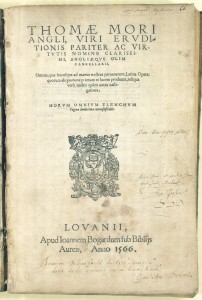

[Right: Titlepage of the 1566 Louvain edition of Thomas More’s works; picture taken from the copy owned by Ben Jonson, the English playwright Ben Jonson. Source.]

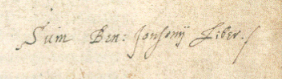

[Left: detail of above, with inscription: “Sum Ben: Jonsonij Liber.”; literally, “I am Ben Johnson’s book.” Further inscriptions on the title page reveal that Johnson gave the book to William Dakins, one of the men who translated the King James Bible, whom Jonson probably met at Westminster School. Dakins, in turn, gave it with an inscription to John Blumfeilde.]

[Left: detail of above, with inscription: “Sum Ben: Jonsonij Liber.”; literally, “I am Ben Johnson’s book.” Further inscriptions on the title page reveal that Johnson gave the book to William Dakins, one of the men who translated the King James Bible, whom Jonson probably met at Westminster School. Dakins, in turn, gave it with an inscription to John Blumfeilde.]

***

On More

- More was an extraordinarily talented, intelligent, and complex individual.

- His most prominent intellectual friendship was with Erasmus of Rotterdam, who wrote a hilarious persiflage on the folly of life in general and the abuses of the Catholic Church in particular known as Encomium Moriae, or “In Praise of Folly,” which punned on More’s name (the Greek word for “folly” sounded similar to More’s name).

- Although he became an influential politician and lawyer, and remained a layman, he seriously contemplated a career in the Church.

- In his own age, he was notable for the attention he paid to his daughters’ education.

- The most definitive intellectual influence on More’s writing was that of Renaissance humanism; yet, after he joined the service of King Henry VIII in 1518, he ceased almost completely to write humanist texts and turned to religious polemics.

- Modern readers may know him best for his 1516 work, Utopia (he coined the term).

- More enjoys a reputation as a staunch man of principle, but not always a pleasant one. On the one hand, as Chancellor of England, he vigorously persecuted and prosecuted Protestant heretics. Six were burned on his watch. His polemics against William Tyndale were influential in the latter’s eventual burning for heresy; and George Foxe, who cataloged the sufferings of Protestant martyrs in England, was convinced that More had personally tortured prisoners on trial for heresy. On the other, More has long been respected for his conviction that authority over Church matters should not be ceded to the secular government, as a consequence of which he was executed in 1535 for his refusal to take the 1534 Oath of Supremacy. Was he moral, or a moralist? The twentieth century tended to see him as moral (as in the much celebrated stage and screen drama, The Man for All Seasons), while more recently, in Wolf Hall (2009), for which she won the Booker Prize, Hilary Mantel has portrayed him as a petty, cruel tyrant.

***

[Right: Paul Scofield as Thomas More, insisting to Parliament that he has not committed treason, in the film version of A Man for All Seasons. Scofield won the Oscar for Best Actor in 1966 for this performance and a BAFTA as well. Source.]

[Right: Paul Scofield as Thomas More, insisting to Parliament that he has not committed treason, in the film version of A Man for All Seasons. Scofield won the Oscar for Best Actor in 1966 for this performance and a BAFTA as well. Source.]

***

***

***

General features of More’s history of Richard

- More probably chose Richard as a topic because of his interest in politics and good government. The book is a foil to Utopia (1516), which discusses perfect government and decries amorality in politics; More saw Richard as the epitome of bad, because amoral, government.

- Humanists saw the point of history as teaching life lessons (historia magistra vitae); despite his many dastardly individual features, Richard in More’s eyes was much more a negative example or pattern rather than a fully formed individual. While More clearly believed what he wrote of Richard to be true, the goal was neither a smear job nor the presentation of evidence about Richard’s reign, but rather the crafting of a tale that criticized amorality, hypocrisy, and vaulting ambition.

- According to scholar George M. Logan, the most important influences on More’s structuring of his history are the Greek author Lucian and the Roman historians Sallust (who wrote histories of the Roman traitors Catiline and Jugurtha) and Tacitus (who wrote a history of the Roman emperor, Tiberius). So great is More’s admiration of Tacitus that he alters facts in his portrayal of Edward IV in order to make his reign seem more like that of Augustus.

- We cannot see More as a straightforward Tudor propagandist; he despised Henry VII.

- More’s history counts as a secondary source in that he did not witness the events he describes. He did draw on primary sources: oral information and reminiscences of people he knew who had lived through events. These included his father (the only source he explicitly names), but more importantly gossip in the household of Bishop John Morton, one of Edward IV’s officials implicated in Hastings’ conspiracy, who survived Richard’s reign. More served in Morton’s household he served as a page from 1490-2.

- While as a public official, More could have consulted extant public records in London, textual comparison suggests that he seems to have done so only once (for Buckingham’s speech of June 26, 1483).

- Though it is extremely unlikely that More knew the work of the second Croyland Continuator, which was unknown outside of its abbey until the later sixteenth century, his account squares with it in important details, another reason to discount the charge that More (or Croyland) were mere Tudor propagandists.

- The only written historical works that More can be proven to have consulted are Fabyan’s New Chronicles of England and France (1516/7) and Great Chronicle of London (ms., 1512).

- No textual evidence suggests that the work on Richard most typically cited as Tudor propaganda, Polydore Vergil’s Anglica historia (ms. 1513), was influential on More.

- The conventions of Renaissance humanist historiography required More to concoct all of the speeches; readers at the time would have known this.

- More’s most prominent literary and linguistic device throughout the work is irony; readers must thus be very careful to discern his meaning, since his words are frequently pointed in specific ways.

- Although the text was one of the most popular works of history in later-sixteenth-century England, it had little influence on history-writing. It made its deepest impact, of course, on Shakespeare, which is the main reason a reader might care about it these days.

- Richard Marius makes the interesting assertion that Richard III is one of the first hypocritical protagonists in the history of western literature.

Further reading

Further reading

- Read More’s History of King Richard III on the web, transcribed from the original English edition of 1557 (with original spelling, but modern typography) here.

- If you like books and ready-to-use scholarship, a fantastic update with extensive notes and sixteenth-century usage retained, but modified to reflect modern spelling, has recently been produced: George M. Logan, ed., The History of Richard III: A Reading Edition (Bloomington: Indianapolis University Press, 2005). This is the one my students will be reading.

- Read More’s history in Latin, in the edition that English playwright Ben Jonson used with his notes visible in the margin, at The Center for Thomas More Studies, in digital facsimile.

- Read More’s others works at Center for Thomas More Studies at the University of Dallas as well.

- Richard III Society resources on More’s history, including excerpts from relevant pieces of Marius’ biography, Thomas More: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1984). (Marius’ biography of More is excellent — a much better work than his disappointingly partisan biography of Martin Luther.)

***

If that’s not too much — I’ll be back next week to discuss some of the fascinating points in More’s retelling of Richard’s story.

Leave a Reply