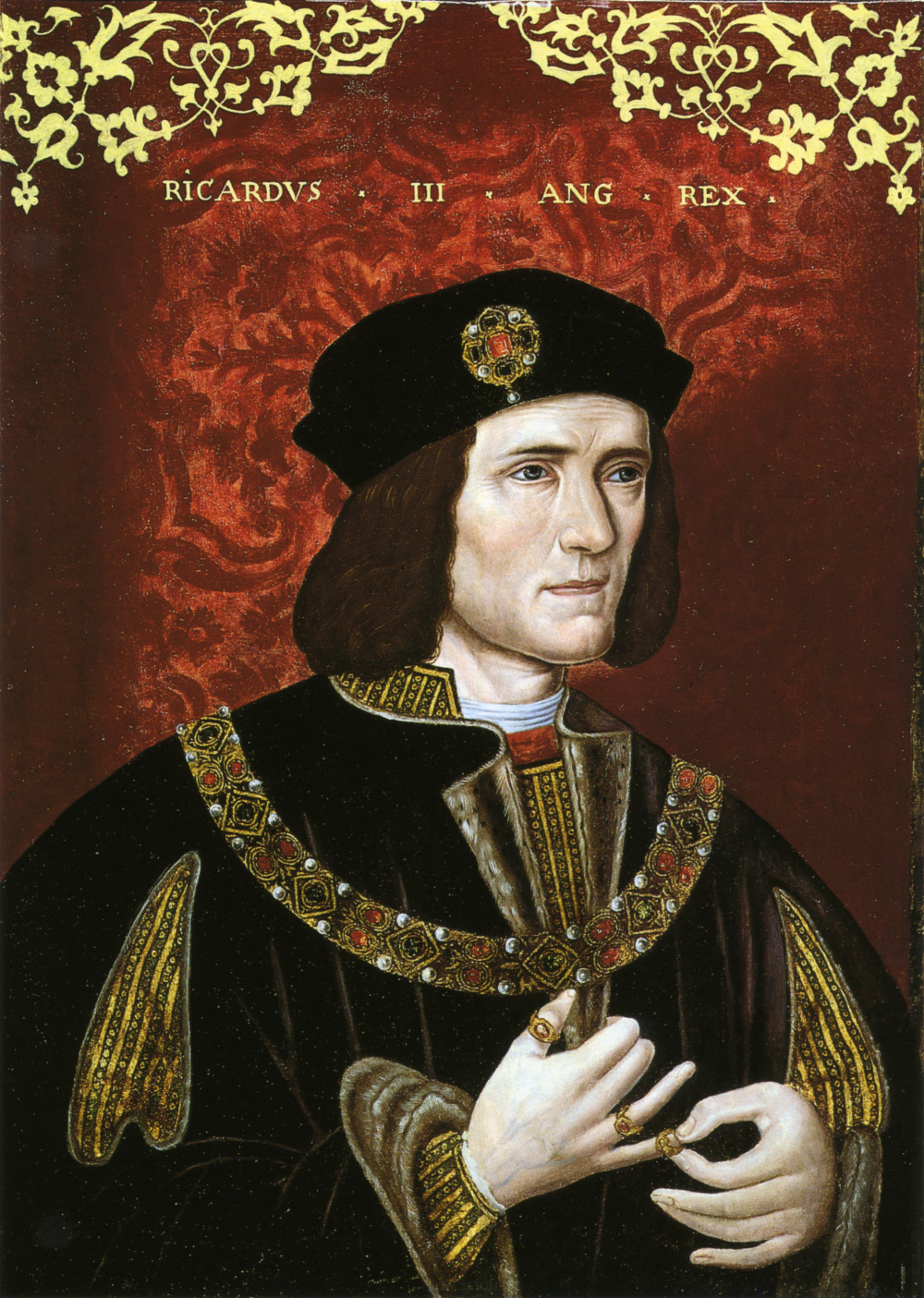

Biography – Richard III

Biographical information about King Richard III kindly provided by the

Richard III Foundation, Inc. (more details here)

[pdf-version – Richard III Biography]

Richard III – A Man and His Times

In 1399, the English Crown changed hands. The childless Richard II, last king in an unbroken line of descent since the Norman Conquest, was deposed and murdered by his cousin Henry of Bolingbroke, who became King Henry IV. The Lancastrian kings – Henry IV, Henry V of Agincourt fame, and Henry VI – descended from John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the third surviving son of Edward III. The heirs of Richard II, stemming from Lionel, Duke of Clarence and Edward, Duke of York, the second and fourth sons of Edward III, were disinherited from the throne.

When Henry V died in 1422, his son Henry was an infant of nine months. A regency directed by a council of leading peers and churchmen were put in place until Henry VI came of age to rule. As was the case with a royal minority, Henry’s childhood and youth were dominated by squabbling nobles determined to control the young king. Unfortunately, Henry VI remained governed by various groups throughout his adult life.

Richard Plantagenet, was born on the 2nd of October, 1452 at Fotheringhay Castle. His father, the Duke of York, the heir of Richard II, possessed a better claim to the English throne than did Henry VI. His mother, Cecily Neville, known as “The Rose of Raby” was a member of the numerous and powerful Neville family.

When Richard was a young child, the political scene in England changed. Henry VI spent large parts of his reign in a catatonic state, unable to recognize his chief ministers or govern the kingdom. The Duke of York, as the leading peer of the realm, was appointed Protector while the king was in a catatonic state.

Meanwhile, Henry’s French queen, Margaret of Anjou, established her own court party and was jealous of the Duke of York’s power and position. She pursued a policy that deliberately alienated the Duke and deprived him of a role and voice in the government.

Margaret, by her partisan politics, made the mistake of attaching the English crown to a faction. Thus, families such as the Nevilles, who were unable to get impartial justice from the king, turned to the Duke of York to redress their local grievances. It was in this fashion that York, who was positioned as a reformer, built his support.

At the Battle of St. Albans, matters came to a head. Over the next five years, the Duke of York’s family lived in a state of uncertainty and risk, their fortunes changing with each battle. In 1459, York was defeated at Ludlow and fled to Ireland. Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, and York’s eldest son, Edward, escaped to Calais in France. The Duke of York claimed the throne; and in December of 1460, York, and his seventeen year old son, Edmund, Duke of Rutland were ambushed and killed at the Battle of Wakefield. The Yorkists accepted York’s eldest son, Edward of March as king. He cemented his title by soundly defeating the Lancastrians at Towton thus deposing Henry VI. During the struggle, Richard, along with his brother, George, were sent to the Netherlands for their safety.

Richard and George returned back to England. Edward IV created George, Duke of Clarence, and shortly thereafter, Richard, was created Duke of Gloucester. In November of 1461, Richard was sent to Middleham Castle in North Yorkshire to begin his knightly training under his cousin, Richard Neville, known as the “Kingmaker”. Richard spent the next three years of his life beginning his apprenticeship in knightly conduct. His training consisted of learning Latin, French, law, mathematics, penmanship, music, horsemanship and military training. He learned to practice with sword, dagger and battle-axe, and how to manage a hawk and learn to hunt. He learned the fine arts of his time – harping, singing, piping and dancing. While he was at Middleham, he would have been in the company of Warwick’s second daughter, the Lady Anne Neville, who was four years his junior.

In 1464, the political scene changed again. While Warwick was conducting negotiations for Edward IV to marry a French princess, Edward took the unprecedented step of secretly marrying a commoner, a Lancastrian widow named Elizabeth Woodville. Elizabeth Woodville had a large family which included two sons, and twelve brothers and sisters. All of the Woodvilles were now entitled to good marriages, which in effect cornered the market on English heirs and heiresses. By elevating the queen’s family, Edward IV was attempting to build a court of his own, dependent upon him, in an effort to assert his independence from Warwick. The Woodvilles were known for their greediness, snobbery and grasping ways. The result of the situation was that the only prospective bridegrooms left of sufficient rank for Warwick’s two heiresses were Edward IV’s young brothers, George and Richard. Edward, who had pulled away from Warwick, forbade the marriages.

With Warwick moving from estrangement to open rebellion, Richard of Gloucester’s time at Middleham came to an end. He was forced to chose between his brother and his cousin of Warwick. In an effort to win their support, Warwick offered George and Richard, his daughters as a bribe. George and Warwick’s older daughter, Isabel were married in Calais in 1469, and George went over to Warwick’s side. Richard remained loyal to his brother, Edward IV.

Warwick and George raised a rebellion which resulted in the deaths of two of the Woodvilles – the father and brother of the Queen. In 1470, Warwick and Clarence formed an alliance with the exiled Lancastrians, including the ex-queen Margaret of Anjou. To seal the bargain, Warwick married his 14 year old daughter Anne to Margaret’s son, Edward of Lancaster. The new alliance invaded England forcing Edward and Richard to flee the country.

The victorious Warwick put Henry VI back on the throne, but his success was short lived. Edward and Richard returned to England after the winter and mustered their forces. Richard persuaded George into a reconciliation, and together the three brothers defeated the Lancastrians at Barnet where Warwick and his brother, John Neville were defeated and killed. Shortly thereafter, Prince Edward of Lancaster was killed in the Battle of Tewkesbury. Contemporary sources state that he was cut down by George of Clarence’s men while fleeing the battlefield. Shortly after Tewksbury, Henry VI died in the Tower of London on the orders of Edward IV leaving no Lancastrian heir.

After the battle of Tewkesbury, George of Clarence took Anne Neville into his charge by sending her to her sister Isabel. Richard was kept occupied helping Edward IV with the reins of the country and was preparing to go north against the Scots. Richard was then Constable and Admiral of England. He additionally received Warwick’s old office of Great Chamberlain and the stewardship of the Duchy of Lancaster beyond Trent. Edward transferred Richard’s seat of power from the Welsh Marches to Yorkshire. Richard relinquished the offices of Chief Justice and Chamberlain of South Wales. Before he set forth for the north, he was given the Warwick estates of Middleham, Sheriff Hutton and Penrith, and later received the remaining portions of the Warwick properties in Yorkshire and Cumberland.

By early August, James III was willing to negotiate the violations of the truce between England and Scotland. By September, Richard returned to London and sought Anne at the residence of George of Clarence. Clarence wanted the vast Neville inheritance for himself. Richard quietly appealed to his brother, Edward IV, and when Richard returned to Clarence’ home, he was informed that Anne was no longer in his household. Clarence hid her in a London cook shop disguised as a servant. Richard found Anne and placed her in the sanctuary of St. Martin Le Grand. It was the only refuge where she would be protected from Clarence and also not placed in any obligation to Richard.

Edward IV requested that his two brothers meet before his council to debate Clarence’ claim over the inheritance of Anne Neville. Clarence claim was illegal and unreasonable. After a long and bitter legal struggle with George, Richard kept the Warwick property already bequeathed to him by Edward IV. Richard relinquished the remainder of Warwick’s lands and property, and surrendered the office of Great Chamberlain of England for the modest office of Warden of the Royal Forests beyond Trent and agreed to George receiving the earldoms of Warwick and Salisbury.

He married Anne Neville in 1472 and they retired to Middleham Castle and began to establish their household. During 1473, Anne gave birth to a son who was named Edward. Richard spent the twelve years of his life bringing peace and order to an otherwise troublesome area of England. Through his hard work and diligence, he attracted the loyalty and trust of the northern gentry. His ability for fairness and justice became his byword. He had a good working reputation of the law, was an able administrator and was militarily formidable. He encouraged trade in Middleham and secured a license from Edward IV so the village could hold two fairs a year. One of his greatest achievements was the Scottish Border campaigns during the years of 1481-82. Under his leadership, on behalf of Edward IV, he won a brilliant campaign against the Scots that is diminished by our lack of understanding of the regions of his times.

Richard III enjoyed a special relationship with the City of York. His affiliation with the City of York and their affection for Richard is evident in their archives. When in York, he often stayed at the Augustinian Friars in Lendal. In 1477, Richard and Anne became members of the Corpus Christi Guild. Richard III, known to be a pious man, was instrumental in setting up no less than ten chantries and procured two licenses to establish two colleges, one at Barnard Castle in County Durham and the other at Middleham. It is known that his favorite residence was Middleham Castle and he was especially generous to the church raising it to the status of collegiate college. The statutes, written in English rather than Latin, were drawn up under his supervision.

In 1478, Richard’s brother, George of Clarence, continued to dabble in treason. George’s wife Isabel had died in childbirth causing George to overstep his bounds for the last time. He accused one of Isabel’s servants of poisoning her and the baby. He took it upon himself to put her on trial and execute her on a malicious charge, thus subverting the king’s justice. George was imprisoned by Edward IV under a sentence of death. Richard hurried south to try to prevent the sentence from being carried out. Hostile chroniclers remarked on how strongly Richard pleaded with Edward for his brother’s life. George of Clarence, was privately executed in a butt of Malmsey in the Tower of London in 1478. After that, Richard went back to Middleham and rarely came to court.

In April of 1483, Edward IV died suddenly. Richard was appointed “Protector” in Edward’s will since Edward’s oldest son was too young to govern on his own. The Woodvilles fearing their power was at an end ignored the will and tried to take control of the young king. If they could crown young Edward before Richard came to London, his protectorship would lapse and the Woodvilles would govern the country.

Richard was notified of his brother’s death by William Hastings, Edward IV’s Lord Chamberlain and friend. Hastings warned Richard of the conspiracy against him and advised him to “get you to London and secure the person of your nephew”. Taking 100 men with him, Richard stopped at York where a requiem mass was said for the soul of his brother; he also led his men in an oath of fealty to his nephew and king. The Woodvilles had raised Edward exclusively and attempted to rule through him once he was crowned. Richard, aided by his cousin, Henry Stafford, the Duke of Buckingham, caught up with the young king’s escort at Stony Stratford. Richard arrested the Woodville conspirators, confiscated barrels of arms and armor and brought Edward V to London for his coronation. Elizabeth Woodville, hearing of the news, fled into sanctuary with her other children. While in London, Richard discovered another plot against his life, this time led by William Hastings.

While Richard was preparing for his nephew’s coronation, Robert Stillington, who had been the Chancellor of England twice under Edward IV, informed Richard that Edward V could not be legally crowned king. Stillington revealed that Edward had been betrothed to another woman when he married Elizabeth Woodville, making all of the royal children illegitimate. Medieval church law held a consummated betrothal to be as legally binding as a marriage, and illegitimate children were not allowed to inherit.

With the untimely death of his brother, Edward IV in 1483, he was petitioned by the Lords and Commons of Parliament to accept the kingship of England. On July 6 1483, Richard III was crowned. His first and only Parliament was held during January and February of 1484. He passed the most enlightened laws on record for the Fifteenth Century. He set up a council of advisors that diplomatically included Lancastrian supporters, administered justice for the poor as well as the rich, established a series of posting stations for royal messengers between the North and London. He fostered the importation of books, commanded laws be written in English instead of Latin so the common people could understand their own laws. He outlawed benevolences, started the system of bail and stopped the intimidation of juries.

During his royal progress of 1483, Richard refused great gifts of cash from various cities saying he would rather have their goodwill than their money. Bishop Thomas Langton said: “He contents the people where he goes best that ever did prince, for many a poor man hath suffered wrong many days, hath been relieved and helped by him, and his commands on his progress. And in many great cities and towns were great sums of money given to him, which he hath refused. On my troth, I never liked the conditions of any prince so well as his. God hath sent him to us for the weal of us all.”

He re-established the Council of the North in July of 1484 and it lasted for more than a century and a half. He established the College of Arms that still exists today. He donated money for the completion of St. George’s Chapel at Windsor and King’s College in Cambridge. He modernized Barnard Castle, built the great hall at Middleham and the great hall at Sudeley Castle. He undertook extensive work at Windsor Castle and ordered the renovation of apartments at one of the towers at Nottingham Castle.

In October of 1483, Richard learned that Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham had begun an uprising against him. Buckingham, who also had a claim to the throne might have thought of himself as another “Kingmaker”. In any event, the rebellion was not as successful as Buckingham had hoped; he was captured and executed for treason. Richard III called him “the most untrue creature living”.

Despite his attempt to safeguard the country, Richard’s kingship was filled with personal tragedy. In 1484, while Anne and Richard were at Nottingham Castle, they received word that their beloved son, Edward, who was at Middleham, died suddenly after a brief illness. The Croyland Chronicler reported “In the following April, on a day, not far from King Edward’s anniversary, all hope of the royal succession raised, died at Middleham castle after a short illness, in 1484, and in the first year of King Richard’s reign. You might have seen the father and mother, after hearing the news at Nottingham where they were then staying, almost out of their minds for a long time when faced with the sudden grief.” Richard appointed his nephew, John De La Pole, Earl of Lincoln, as his new heir.

His wife, Anne, never recovered from the loss of her son, and died almost a year later. Her body was borne to Westminster Abbey and laid to rest on the south side of St. Edward’s Chapel. Richard wept openly at her funeral and shut himself off for three days. In eighteen months, Richard lost his brother, son and wife.

A hostile chronicler reported that while Queen Anne was ailing, Richard hastened her death to marry his niece, Elizabeth of York. The comment arose from a chronicler because his niece appeared in a dress made from the same material as that of the Queen. The dress was due more to the Queen’s kindness to her niece. Upon hearing the rumor, Richard sent Elizabeth away to join the household at Sheriff Hutton Castle where his other nieces and nephews lived. Then he gathered together the most influential men in London and publicly denounced the rumor. This act demonstrates his integrity and courage.

The unofficial heir to Lancaster was now Henry Tudor. Tudor was descended on his mother’s side from John of Gaunt’s illegitimate Beaufort children, and on his father’s side from an unauthorized liaison between Henry V’s widowed French queen, Katherine of Valois and Owen Tudor, a Welsh esquire. With the backing of the French king and an army gathered from the jails and mercenaries of France and the remnants of the Lancastrian army, they prepared to invade England in the summer of 1485. By May, Richard left London for the last time and journeyed to Windsor. His Knights and Esquires of his Household accompanied him. Francis, Viscount Lovel, was sent to Southampton to lead the forces in case Tudor landed in the southern counties. John, Duke of Norfolk, was stationed in Essex. Sir Robert Brackenbury, the Constable of the Tower, was defending the capital.

Richard left Windsor and departed for Kenilworth. By the middle of June, he was at the centre of his realm at Nottingham Castle. He sent his niece, Elizabeth of York, along with her sisters, his nephews and his illegitimate son, John of Gloucester, to Sheriff Hutton. From Nottingham, he sent instructions to the commissioners of array in all the shires alerting them to the invasion. On the 11of August, a messenger brought news to Richard, who had been at Beskwood Lodge, that Henry Tudor had landed at Milford Haven in South Wales on Sunday, the 7th of August.

Richard sent word to Northumberland, Brackenbury, Lovel and Norfolk commanding them to join him in Leicester. On Friday, August 19th, Richard left Nottingham and traveled south toward the city of Leicester. On the 20th of August, Richard was in Leicester with his captains mustering his men. By late afternoon, he learned from his scouts that the army of Lord Stanley was at Stoke Golding while William Stanley was at Shenton. Henry Tudor and his men were at Atherstone. On Sunday, the 21st of August, Richard and his royal army left the city of Leicester. Richard and his commanders took their position on Ambion Hill at Bosworth Field.

The Duke of Northumberland and Lords Thomas and William Stanley, along with their troops, waited out the start of the battle while the rest of Richard’s army engaged Henry’s exiles and French mercenaries. After Richard’s commander, the Duke of Norfolk was killed, Richard tried to win the conflict by a surprise charge at Tudor, before the waiting armies of the Stanley and Northumberland chose sides. Richard led his household men against Tudor. Richard killed Tudor’s standard bearer, William Brandon, and a giant of a man named Sir John Cheyney. When Richard was only a few feet away from Tudor, Stanley’s army moved, surrounding and killing Richard and the men of his Household.

As he swung his battle-axe, he was known to have shouted “Treason – Treason – Treason” as he was slain. Northumberland and his army remained waiting on the sidelines and never engaged in battle to assist Richard.

Richard was 32 years old when he was killed at the Battle of Bosworth. His reign showed great promise. He was the only king from the north, the last of the Plantagenet kings and the last king of England to die in battle. Polydore Vergil, Henry Tudor’s official historian wrote “King Richard, alone, was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies”.

Through betrayal, Henry Tudor became Henry VII. Henry attempted to backdate his reign to the date before the battle in order to attaint for treason men who had fought for King Richard III.

John Spooner, rode into the city of York the day after the battle. The Mayor and Alderman of York assembled in the council chamber and recorded “it was recorded by John Spooner that King Richard, late mercifully reigning upon us, was piteously slane and murdered to the grete heaviness of this citie”.

Henry VII’s reign was not the golden age his writers proclaimed. Rumors and Yorkist pretenders plagued his reign. Henry VII wanted to glorify the Tudors and justify his kingship. In the Tudor view of English history, the coming of Henry VII saved England from disorder, bloodshed and evil, as personified by the king Henry had defeated. Thus chroniclers and historians under Tudor began a campaign to blacken Richard’s name and reputation.

With the accession of James I, his defenders began to speak out, and into the present day, the defenders of King Richard III continue to speak out in his defense.

King Richard III appealed to the ideals of loyalty, lordship and honor. He knew how to command, how to reward, but most of all, he knew how to inspire.

Sir Clements Markham stated: “The true picture of our last Plantagenet king is not unpleasant to look upon, when the accumulated garbage and filth of centuries of calumny have been cleared off the surface”.

The handiwork of the Tudor historians against this much maligned monarch can be summed up best in Paul Murray Kendall’s 1955 biography – “What a tribute this is for art – what a misfortune this is for history”.

©The Richard III Foundation, Inc.