King Richard in Hobbit Fever?

Yesterday, November 28th 2012, the Premiere-event for “The Hobbit” by Sir Peter Jackson took place in Wellington, New Zealand.

But what can this have to do with King Richard III?

A lot, considering Mr. Armitage, the actor who plays the leading character Thorin Oakenshield in “The Hobbit” and the reason for the existence of this website, took part.

On the red carpet, Mr. Armitage was interviewed by many reporters, but the key question for us came from a fan in the crowd, who was following the red carpet event in Wellington.

Unfortunately, in the material broadcasted by TVNZ in the One News Hobbit Special, which was presented by Wendy Petrie, I can’t make out the question of the fan, though from the voice it is a woman. The reporter next to her unfortunately does not lend his microphone to her, but Mr. Armitage’s answer is recorded very well:

I would love to play King Richard. I may be a little bit too old and a little bit too tall, – but I played a dwarf.

TVNZ One News does not enable an embed code, so here comes the link to the full Hobbit Special, which takes about an hour (and has embedded advertisements).

The interview with Richard Armitage starts at about 23:30 and the quote is at 24:20.

Let’s loose no further time, let’s try to get him into the role of King Richard III by signing the petition !

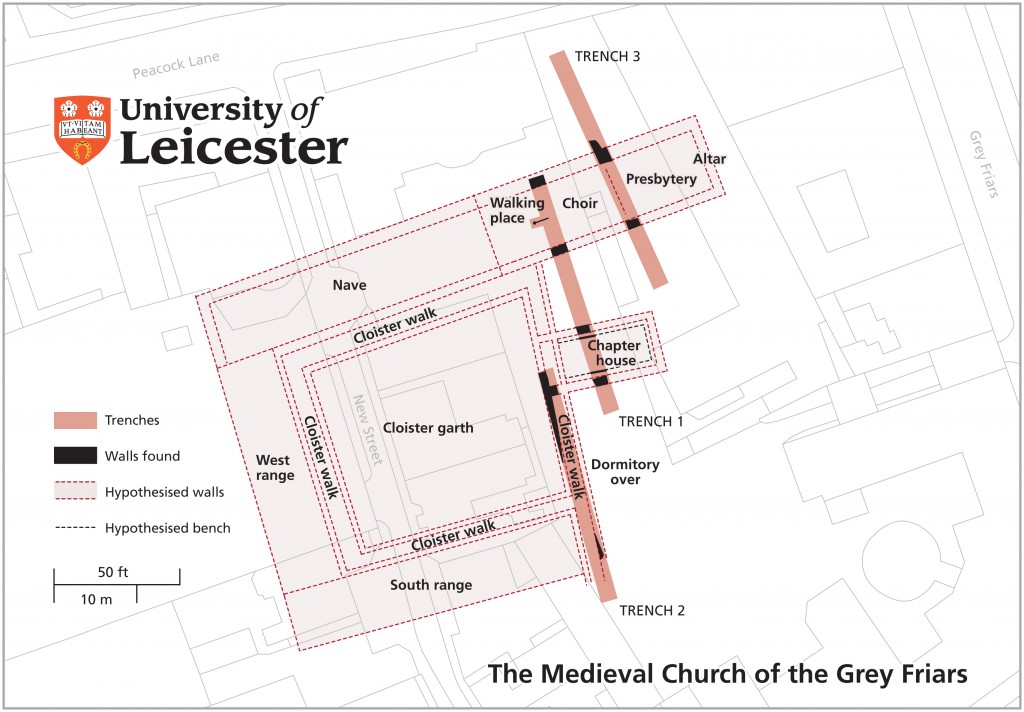

Finds and Research at Grey Friars in Leicester

An overview of the late discoveries and knowledge growth through the archaeological research in Leicester

Trench1-1 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

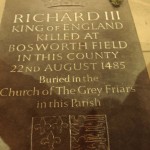

The University of Leicester lately revealed, that finding the human remains, which are believed to be of King Richard III, was a close call.

During the Victorian Era, a building was created at the site in Leicester, which nearly destroyed the bones, as it dug almost deep enough to unearth them.

At that time, when King Richard III still was believed to have been dumped into the river Soar, the connection to King Richard III never would have been made and so the chance to ever prove the identity of the bones by comparing them to Mr. Michael Ibsen, his 17th generation relative in the female line, would have been forever lost.

Our first-hand witness of the digging area, Ali from the RichardArmitageNet.com website, in her pictures (full list at the end of this article) shows the close run of the digging very well. (Thank you very much for the wonderful pictures, Ali !)

The human remains, believed to be King Richard III, were found in Trench 1 at the Grey Friars’ area.

One foot above the grave, the remains of the Victorian building start.

Mathew Morris, the site director in Leicester:

It was incredibly lucky. If the Victorians had dug down 30 cm more they would have built on top of the remains and destroyed them.

Sir Peter Soulsby, the understandably proud City Mayor of Leicester, about the hair’s breadth of the find:

His [the male skeleton, believed to belong to King Richard III] head was discovered from the foundations of a Victorian building. They obviously did not discover anything and probably would not have been aware of the importance of the site.

In my view, it was also luck that the car park was built on top and preserved all that lay below, without further building work done in that area. So now, the remains of the Medieval church and its structure could be discovered and re-constructed in a way to allow conclusions of where the choir of the church, the most likely and by contemporary sources mentioned area of King Richard III’s resting place, was.

This way, the find became possible and the archaeological team had hints where especially to look for King Richard III.

Michael Ibsen, the 17th generation relative of King Richard III in the female line, is fully supporting the search for King Richard III:

It is exciting to be able to play a small part in something that is potentially so historically important, but also nerve-wracking because it still remains to be seen whether the DNA tests will be conclusive.

Historian Dr. Ashdown-Hill, who’s research made this new search for King Richard III possible, describes his experiences at the Leicester car park:

When I looked into the grave and saw the skeleton, I was deeply moved. I feel that the case for the identity of the body is already pretty strong: male; right age group and social class; died a violent death; had a twisted spine; found in the right place.

The University of Leicester does a lot to satisfy the immense interest in King Richard III and the archaeological research. They held guided tours and opened the digging area for the enthusiastic public, storming the ground. This gave our picture source, Ali, to all Richard Armitage fans well known from her website RichardArmitageNet.com, the chance to visit and take the wonderful photos of the location accompanying this article. Here are the photos of the area , where the supposed remains of King Richard III were found:

Leicester-Richard III Burial Place (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

Leicester-Richard III Burial Place 2 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

The search for King Richard III is not over with finding the bones at the supposed location in the found and virtually reconstructed church area of the former Greyfriar’s church.

Further tests are necessary to determine, if the bones, which already have significant signs to make it very likely, indeed belong to King Richard III.

- DNA tests are done (samples taken from the teeth and a long bone, so that DNA can be extracted for the comparison with the mtDNA of Michael Ibsen.)

- Modern DNA test from Michael Ibsen is carried out in Leicester, while extraction of DNA from the skeleton and testing ‘ancient DNA’ is taking place in partnership with specialised facilities, which allow the tests without risk of contamination.

- separate genealogical study, to verify Mr. Michael Ibsen’s connection to the Plantagenets. Research is also trying to verify a second line of descent, as further comparison basis.

- environmental sampling (to determine more about the burial practice, living conditions, health and regional descendance of the found person)

- radiocarbon dating (Executed by two separate labs. Should determine the date the individual died within a range of about 80 years. – Though the best known historical method to determine, seems a rather vague proof in this case.)

- computer-tomography (CT) scan (which will allow scientists to build up a 3-D digital image of the individual. Goal is to reconstruct the individual’s face, like it is done in murder investigations or e.g. to reconstruct the face of King Tutankhamun, after scanning his 3.000 year old mummy.)

- samples of dental calculus – mineralised dental plaque is taken (which will allow conclusions about the person’s diet, health and living conditions.)

- the skeleton has been cleaned and examined, to determine the individual’s age, build and the nature of its spinal condition. Particular attention has the trauma and injury of the skull of the skeleton, which may indicate a battle wound. Medical examinations are done and specialists in medieval battles and weaponry are advising the team on the kinds of instruments that may have caused the damage.)

- forensic pathologists at the University’s East Midlands Forensic Pathology Unit are also working on the case, to determine the cause of death.

These tests need rigorouse procedures and elaborate equipment and specialist facilities to enable a positive determination of the identity.

Richard Buckley summarises the magnitude of undertaken researches as follows:

We are looking at many different lines of enquiry, the evidence from which all add up to give us more assurance about the identity of the individual. As well as the DNA testing, we have to take in all of the other pieces of evidence which tell us about the person’s lifestyle – including his health and where he grew up.

There are many specialists involved in the process, and so we have to coordinate all of the tests so the analysis is done in a specific order.

The ancient DNA testing in particular takes time and we need to work in partnership with specialist facilities. It is not like in CSI, where DNA testing can be done almost immediately, anywhere – we are reliant on the specialist process and facilities to successfully extract ancient DNA.

Professor Lin Foxhall, Head of Archaeology and Ancient History at the University of Leicester, said about the reliability of the research:

Much research and investigation needs to be done if we are to have a chance of identifying this individual more securely, and the identification may never be one hundred per cent secure. […] it is part of the rigour of academic research that we thoroughly examine all the evidence before reaching a conclusion.

What this find possibly can mean for future generations of historians, Professor Norman Housley and Dr. Andrew Hopper of the School of Historical Studies tried to anticipate:

The discovery of the body will be significant because of what is already being indicated about the cause of death. The apparent evidence of battle injuries will stimulate debate about exactly how Richard was killed at Bosworth, and beyond that, about close combat in medieval battles. This is fitting because Richard polarised opinion during his life and from beyond the grave; his reliance on a northern regional powerbase to maintain his rule fostered a north-south divide in allegiance partially reflected in the historiography since.

They even go so far as that the find can bring closure to historical debates about King Richard III and the Wars of the Roses:

It will bring a pleasing sense of closure to our knowledge of the vicious civil war which ushered in the Tudor dynasty […].

Philippa Langley, initiating force of the search for King Richard III and member of the Richard III Society, describes the immense effect of the possible find:

The dig in Leicester is exploding many of the myths that surround King Richard. It is also questioning the work of many of our illustrious writers.

It seems that despite Thomas More, Richard did not have a withered arm, that despite William Shakespeare, Richard did not have a hunchback. And despite John Speede, Richard’s remains were not exhumed and taken to the river Soar.

If the remains are identified as being those of King Richard these are just some of the myths that have already been busted. And, having watched the exhumation, I believe there may be more myths to follow.

That the University of Leicester already is proud of their wonderful research, though the results are not yet proven by the laboratorial results, shows the visit of South African social rights activist Emeritus Archbishop of Cape Town Desmond Tutu, who got the Nobel Peace Price in the year 1984. The University team behind the search presented the research and methods to him at his visit on November 14th, 2012.

He met key members of the research, Professor Lin Foxhall, Richard Buckley, Dr. Turi King from the University’s Department of Genetics and Dr. Jo Appleby of the School of Archaeology and Ancient History.

Prof. Lin Foxhall describes this extraordinary event:

It is an honour to be able to present our ongoing work on the Grey Friars Project – which represents an important chapter in English History – to someone of the stature of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. […] We would like him to see the work that we are doing, not only in researching the past but also with people in the present.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who is honorary member of the University of Leicester, went on to hold ‘The Provost Derek Hole’ annual lecture 2012 on “Public faith in a secular age”, which is available to watch on YouTube here.

The debate about the archaeological research in Leicester prevailingly focuses on the skeleton, which is believed to be of King Richard III, but the second skeleton found rarely is mentioned. The University of Leicester and the archaeological team also research in depths here and the first results already are impressive.

What is known about the second skeleton is, that the remains of the second skeleton were found disarticulated and belonged to a female.

Mathew Morris, site director of the University of Leicester Archaeological Services, describes the direction where the research about this female skeleton is heading:

It wasn’t unexpected finding the remains of a woman buried in the friary. We know of at least one woman connected with the friary, Ellen Luenor, a possible benefactor and founder with her husband, Gilbert.

However the friary would have administered to the poor, sick and homeless as well, and without knowing where Ellen Luenor had been originally buried we are unlikely to ever know who the remains are of, or why she was buried there.

Philippa Langley, who did extensive research about the church of the Grey Friars together with Dr. Ashdown-Hill for over three years prior to the real digging, established seven potential named burials in addition to King Richard III’s in the church. Only one of those further seven was female, that of Ellen Luenor, wife of Gilbert Luenor, a possible founder and benefactor of the Grey Friars, who was buried around 1250.

Philippa Langley:

It was a tenuous connection but an intriguing one only mentioned, as far as we could tell, by the 16th century historian John Stow. […]

It’s a slim chance that they could be Ellen, but at least we have a female name to attribute to them and at the moment there is no other.

The entire dig was filmed by Darlow Smithson Productions for a Channel 4 Documentary. – Though we requested further details, the finishing date and screening time are still undetermined. (And as the not very polite answer suggests, we were not the only one’s to ask for more details.)

<< Please click on the images to see a large version. Click again to return here. >>

- Leicester – Artefacts (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Leicester-Guildhall-1 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Leicester-Guildhall-2 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Leicester-Cathedral (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Leicester-Cathedral-2 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Leicester-Cathedral-3 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Leicester-Cathedral-4 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Leicester-Richard III Burial Place (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Leicester-Richard III Burial Place 2 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench1-1 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench1-2 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench1-3 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench1-4 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench1-5 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench1-6 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench1-7 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench1-8 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench1-9 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench2-1 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench2-2 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench2-3 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

- Trench2-4 (Source: Ali, RichardArmitageNet.com)

Collective Reading – Thanksgiving Break

♛ Collective Reading ♛

As family events on the long Thanksgiving weekend take up lots of time and leave less time for the collective reading, the discussion takes a break today and will resume chat and discussion of the next chapters at the usual time and place next Sunday.

December 2nd, 2012: Discussion of the scheduled next chapters: Book II, chapter 13 – Book III, chapter 4

- Twitter-Chat-Group: Twitter discussion under hashtag #RA4R3

- Facebook-Group: Institute of Armitage Studies

- Schedule on Blog: Distracted in Reality by Fanny/iz4blue

♛ Leicester News ♛

- redOrbit: Scientists Searching For Richard III: ‘It’s Not Like CSI’, by Alan McStravick (15.11.2012)

- This is Leicester: Archbishop Desmond Tutu discusses faith and Richard III during Leicester Uni visit, by Leicester Mercury (15.11.2012)

- Fox News.com: Possible skeleton of King Richard III in testing, by Stephanie Pappas (16.11.2012)

- BBC Radio Leicester: Prof. Lin Foxhall interviewed by BBC Radio Leicester about King Richard III identification, expected beginning of the year 2013 (Audio-Interview 19.11.2012)

- BBC News Leicester: Richard III dig: Results expected in January (19.11.2012)

- Story of Leicester: Richard III Walking Tour – Take a walk (or virtual walk) through Leicester and visit its Richard III sights.

- Houston Chronicle: UK find revives the debate over Richard III’s legacy, by Anthony Faiola, Washington Post – A not in all points correct article, which seems to have been written a bit in haste and negligently, though it does combine some of the points in the War of the Cities between Leicester and York to some length. The article ends in a way as if to forcibly come to an ending and so comes to a disappointing kill-it-all conclusion, which is used to death by all Richard III opponents and gets a bit boring and lame by now. (24.11.2012)

I mention this last article, as it is one of the cases that the topic is discussed at length by a foreign, in this case an U.S. newspaper and this in my view makes it worth to mention. Otherwise, I try to avoid articles, which bring no news, but just repeat what is already published in other articles.

I don’t want to bore you with endless repetitions of the same content.

Leicester Cathedral – Personal News

♛ Leicester Cathedral ♛

Kathrynruthd, blogger, supporter of our film-petition and follower of Mr. Armitage’s career, lives in Leicester and on her blog takes us with her on a knowledgeable tour, showing us Leicester Cathedral:

“Fit for a King?“

Her very personal review about the intended last resting place for King Richard III, very much gripped me.

Especially the sentence:

[…] and if he’s [King Richard III] reinterred in Leicester Cathedral, he will be made to feel welcome … very welcome.

That is what I so much wish for, that wherever he may be buried at last, that he is welcomed and treated with respect there.

Thank you very much, Kathrynruthd, for you wonderful presentation of Leicester Cathedral!

If you want to vote for Leicester, in this ongoing battle of the cities, here is the link to the petition for Leicester Cathedral, started by Roy Shakespeare. (Note: Petition is open for British citizens or U.K. residents only.)

♛ Leicester News ♛

- This is Leicester: Virtuous or villain? Debating Richard III, by Leicester Mercury – Announcement of today’s (November 14th, 2012) debate “The Villain and the Man of Prayer – Aspects of Richard III” held by Miriam Stevenson , taking place Thursday, 14th of November 2012, between 6pm and 7pm, at Bishop Street Methodist Church – beside Town Hall Square – Leicester. (13.11.2012)

- Daily Mail: Charles is dwarfed by a dwarf: How ‘servant’ Hobbit star made prince’s birthday, by Mark Duell (14.11.2012) – Real and fictional royalty, ancient and current, united in the film “The Hobbit”. If it is King Richard III, brought in by Mr. Armitage, Prince Charles or dwarf king Thorin Oakenshield, “The Hobbit” and Sir Peter Jackson certainly seem to have some kind of royal blessing.

Fifteenth-century remedies against witchcraft, part 2

***

Wishing those who marked these days — belatedly — a meaningful All Souls’ Day and Día de los muertos! I miss living more directly in the Mexican diaspora and hope that anyone who had access to one ate a piece of pan de muerto in my honor (picture at right; source).

Wishing those who marked these days — belatedly — a meaningful All Souls’ Day and Día de los muertos! I miss living more directly in the Mexican diaspora and hope that anyone who had access to one ate a piece of pan de muerto in my honor (picture at right; source).

***

Turning to England, I was alerted this morning that the BBC HistoryExtra currently offers a quiz to determine whether you would have been accused of witchcraft. It’s well-constructed, if a bit simplistic, and based on the information I gave, I would have been accused. (Hmmm. And it’s not because I’ve read the Malleus maleficarum repeatedly.) There’s also a podcast on the significance of the Plantagenets to British history, which I am downloading for later. Apropos of Plantagenets, Sharon Kay Penman noted, on her fan club facebook page (you must join to see), that today marks the anniversary of the birth of the ill-fated Edward V and his younger sister, Anne.

[Left: The surviving main building at the abbey of Cluny, where Abbot Odilo originated the celebration of All Souls’ Day in the early eleventh century. The spread of the celebration of this holiday is associated with growing belief in the doctrine of purgatory in the western church after the mid-tenth century. Source.]

[Left: The surviving main building at the abbey of Cluny, where Abbot Odilo originated the celebration of All Souls’ Day in the early eleventh century. The spread of the celebration of this holiday is associated with growing belief in the doctrine of purgatory in the western church after the mid-tenth century. Source.]

***

King Richard Magic Week continues below. Check out posts on the witchcraft’s threat to the crown in the fifteenth century, Gloucester’s witchcraft accusations in Richard III, and elite remedies against witchcraft.

***

Part II, question 2, ch. 6, of Malleus maleficarum, where exorcism to end bewitchment is discussed, is extraordinarily rich. A complete interpretation of it would explode the bounds of a single post. For instance, it treads perilously close to heresy several times — by proposing a remedy for witchcraft that is prohibited by canon law and was illegal in civil codes at the time in much of continental Europe (rebaptizing the victim); by charging that a priest in a state of grace is a more effective practitioner of an exorcism than a sinful one (a loophole may be that although the belief that a priest must be in a state of grace to perform a sacrament is heretical, exorcism is not a sacrament); and by suggesting that some baptisms were not effective the first time (clearly heretical because the sacraments work ex opere operato). But we’re interested in magic, not in heresy, here!

I noted in the previous post that the only remedy the Malleus maleficarum offers against witchcraft affecting the body is exorcism: the ritual or verbal casting out of demons or the Devil. In understanding the recommendations, it is helpful to consider what fifteenth-century authors might have meant by exorcism — since the common picture in the minds of most people today comes from an infamous 1971 film. (Maybe not so infamous to younger viewers — a review by a fellow Richard Armitage blogger expresses some confusion about the fame of the film.) And although the rank of “exorcist” was a minor order of the Church, it means something different now than it did in the 1470s. Indeed, the work stresses that one must not have taken the order in order to perform an exorcism.

Having thus discounted the possibility that exorcism differs from witchcraft because of the clerical status of its practitioner, the authors must set up a means by which an afflicted person can judge whether any exorcism would be lawful. They write:

The clergy have become too slothful to use any more the lawful words when they visit the sick. On this account … such lawful exorcisms may be used by a religious and discreet priest, or by a layman, or even by a woman of good life and proved discretion; by the offering of lawful prayers upon the sick. … And such persons are not to be prevented from practicing it in this way; unless perhaps it is feared that, following their example, other indiscreet persons should make improper use of incantations.

If the practitioner is pious, the victim may obtain help. The authors then list seven conditions for judging the lawfulness of remedies offered by such people: (1) no explicit or implicit invocation of devils; (2) no unknown names in charms; (3) nothing untrue in the words / no doggerel; (4) no written characters besides the sign of the cross — the authors note that this provision condemns most charms carried by soldiers; (5) no requirements regarding the method of writing or binding the charm on the person’s body; (6) use of scripture or words of saints must rely on effect from divine virtue or the relics of the saints; (7) the effect must be left open to divine will. “If none of these conditions be broken,” the authors conclude, “the incantation will be lawful.” These conditions established, the authors continue to note that a charm fixed around the neck is effective if the person who wears it understands the words in the charm; but if not, “it is enough if such a man fixes his thoughts on the divine virtue.”

If these simple measures have no effect, further steps can be taken. The afflicted person should make a good confession. Then, “let a diligent search be made in all corners and in the beds and mattresses and under the threshold of the door, in case some instrument of witchcraft may be found … and … all bedclothes and garments should be renewed, and … he should change his house and dwelling.” If these things do not avail, the afflicted should go the church on a feast day, take a holy candle, and pray. Various sacramentals (stole, holy water) should be employed. This ritual should be followed three times a week until successful. The victim should also receive the Eucharist, but only if he has not been excommunicated. Finally, the beginning words of the Gospel of John (“In the beginning was the Word …”) should be written and hung around his neck. (This widespread remedy against demonic attack in extremis is frequently evidenced in sources concerning women in childbirth, into the mid-sixteenth century.)

The authors then discuss reasons why exorcism — which is not a sacrament, so it doesn’t work automatically — may not work. Most of these relate to want of faith or piety in the victim, those praying for the victim or the exorcist, but the authors also suggest that the remedy may be flawed. Therefore the authors cite a final remedy for stubborn cases: rebaptism:

“It is said … of those who walk in their sleep during the night over high buildings without any harm, that it is the work of evil spirits who thus lead them; and many affirm that when such people are rebaptized they are much benefited. And it is wonderful that, when they are called by their own names, they suddenly fall to earth, as if that name had not been given to them in proper form at their baptism.”

Finally, the authors conclude with a discussion of natural remedies — which probably would have been the first resort of many people who sought to counter black magic with white. “If natural objects are used in a simple way to produce certain effects for which they are thought to have some natural virtue,” the authors conclude, “this is not unlawful. But if there are joined to this certain characters and unknown signs and vain observations, which manifestly cannot have any natural efficacy, then it is superstitious and unlawful.”

***

In the attempt to understand fifteenth-century piety and religion, we could make several observations about this body of remedies.

First, we’re clearly dealing with a mostly illiterate society here — so the shape of marks is more important than letters; and the remedies are claimed to work even if the victim is too uneducated to understand the sense of the words being used — which makes scriptural words hardly indistinguishable from magical marks, and one wonders how most people might have made the distinction.

Second, in contrast to the sort of universalizing statements the Latin church had regularly made about itself since at least the beginning of the thirteenth century, dealing with witchcraft gives the victim little reliance on the Church. After baptism, which includes a brief formula and prayer of exorcism (Exorcizo te, immunde spiritus, in nomine Patris + et Filii + et Spiritus + Sancti, ut exeas, et recedas ab hoc famulo …), the church has no additional tool to cast out the devil automatically, only a ritual (exorcism) that is dependent on the faith of the victim and those supporting him in his ordeal. Along the same lines, the authors suggest repeatedly that the clergy may not necessarily offer any help — they are too lazy, or not in a state of grace, or not pious enough. I tend not to be a big fan of the scholarly argument that Europeans on the eve of the Reformation were constantly tortured by the imminence of damnation and that medieval piety did nothing against such fears — but depending on how we understand it, this discussion of exorcism offers some anchoring for that position, even if the Reformation — which is only thirty years in the future at this point — clearly expanded both fears and persecutions of sorcery of various types.

Finally, and decisively, the remedies proposed look from our perspective suspiciously like witchcraft themselves in that they both explicitly legitimate the practice of witchcraft by giving it credibility (if you’re suffering, look for an enchanted object that’s causing it), and by suggesting mechanisms (charms, language, contact with relics) strongly similar to those used by witches to cause enchantments in the first place. Baptism is supposed to call demons out of the body of the baptizand — but the discussion if its efficacy implies that it also give the baptizand a name by which he may be called, putting him in a parallel position to beings, like demons and spirits, that may be summoned. The authors of the work seem unaware of or uninterested in this relationship, a parallelism that suggests that they themselves were incorporated into the paradigm that made witchcraft accusations simply “make sense” in explaining the world.

***

And Shakespeare’s Gloucester? He could have undertaken any of these things — but, the implication is, he himself is so implicated in the disordered and unlawful relationships exemplified by witchcraft that he choose to wreak further havoc rather than dealing with them.

***

Calendar-wise, Magic Week 2012 is over, but I had two more subjects planned for this series. I will try to get to them this week. I’m also happy to answer questions if anything’s unclear.

Is it or is it Not… – Leicester News

♛ Leicester News ♛

You thought with us, the battle of the towns now is over? – No, not yet, not really, not finally, it seems, now the Ministry of Justice rowed back and though tending to Leicester Cathedral, will officially decide when the laboratory results are definitive and can confirm the archaeological find as being King Richard III. The results are expected for about January or February 2013.

What else could we expect – it after all is one of the battles in the “Wars of the Roses” and those started and ebbed down and started again and were bitterly fought on all sides. And when you thought, all sides were at their wits end and finally in peace, new opponents turned up.

- Call to give Richard III York burial – The York Press, by Dan Bean (30.10.12)

Mike Bennett, custodian of the Richard III Museum in York, (not surprisingly) fights for York as burial place. - Should Richard III’s remains be interred in Gloucester Cathedral? – This is Gloucestershire (01.11.2012)

Retired couple, Ted and Anne Hancock, fight for King Richard III to be interred in Gloucester Cathedral, as he was the most famous Duke of Gloucester. - Government back-track on burial of Richard III in Leicester – The Hinckley Times, by Katy Hallam (01.11.2012)

- Bosworth welcomes ‘royal visitor’ – This is Leicestershire, by Tom Mack, Leicester Mercury (02.11.2012)

Report about Michael Ibsen and historian Dr. John Ashdown-Hill visiting the Bosworth Field visitor centre.

And don’t mix up the pictures of a skeleton from Bosworth Field with King Richard III. I got messages stating that, but it is not him!

Protecting Richard: Fifteenth-century remedies against witchcraft, part 1

***

King Richard Magic Week 2012 continues! I apologize for not posting on Halloween — Wednesday is a big teaching / office / service day for me. Happy Samhain to those who celebrated it and Happy All Saints’ Day to those celebrating that.

***

In the first post in this series, on the reality of witchcraft threats in early modern England, I argued that discussions of witchcraft need to be taken seriously on their own terms (as opposed to being understood as a symptom or reflection of something else). In the second post, on Gloucester’s witchcraft accusations in Shakespeare’s Richard III, I argued, given that Shakespeare can be assumed to share the beliefs of his age, Gloucester’s use of the witchcraft accusation against Elizabeth and Jane Shore is a way for the characters in the play and its audiences to account for the disorder of a political world in which Gloucester could accuse Hastings, historically one of his family’s most loyal supporters, with treason. Following on those two posts, given that witchcraft was real for Richard III’s contemporaries and that it was a factor for a century later in explaining the ills of politics gone wrong, as another means of talking about fifteenth-century ideas, I want to ask a hypothetical counterfactual. Assuming that Richard III had been beset by witchcraft, how could he have cured this situation?

In the first post in this series, on the reality of witchcraft threats in early modern England, I argued that discussions of witchcraft need to be taken seriously on their own terms (as opposed to being understood as a symptom or reflection of something else). In the second post, on Gloucester’s witchcraft accusations in Shakespeare’s Richard III, I argued, given that Shakespeare can be assumed to share the beliefs of his age, Gloucester’s use of the witchcraft accusation against Elizabeth and Jane Shore is a way for the characters in the play and its audiences to account for the disorder of a political world in which Gloucester could accuse Hastings, historically one of his family’s most loyal supporters, with treason. Following on those two posts, given that witchcraft was real for Richard III’s contemporaries and that it was a factor for a century later in explaining the ills of politics gone wrong, as another means of talking about fifteenth-century ideas, I want to ask a hypothetical counterfactual. Assuming that Richard III had been beset by witchcraft, how could he have cured this situation?

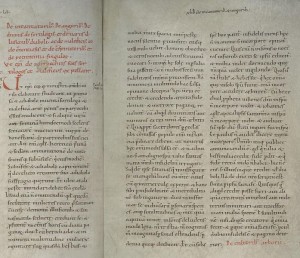

[Right: Canon episcopi in Hs. 119 (Cologne), a ninth-century passage in canon law on witchcraft beliefs. Source.]

***

Were we able to juxtapose Richard and Shakespeare, we would likely discover that Shakespeare, writing around 1591, was probably significantly more knowledgeable about witchcraft than Richard, who died over a century earlier, would have been. Richard lived in a watershed period for explaining and understanding witchcraft. Medieval monarchs and churchmen alike had been negative to skeptical about popular beliefs about the efficacy of witchcraft, which they associated with paganism, until approximately the mid-thirteenth century. Indeed, this skepticism had been incorporated into canon law via the text of Canon episocopi, a text that argued that people who believed in efficacious witchcraft were heretics who had lost their faith and succumbed to the Devil. The effects of witchcraft occurred in the imagination, not in physical reality.

The text of this document points implicitly to an “incomplete” Christianization of Europe before the Reformation — an possibility substantiated in historical works by scholars like Jean Delumeau, especially Le Catholicisme entre Luther et Voltaire (1971). Many pre-Christian beliefs and traditions persisted in the popular Latin Christianity of the fifteenth-century, some of which were shared in elite populations as well. Most English people maintained some belief in both white magic and its opposite, maleficium (which we usually translate, a bit loosely, as sorcery), and many might have taken resort in popular magic as a way of dealing with their world through charms, potions, or amulets, but trials for maleficium were rare and punishments for the convicted remained light throughout the Middle Ages.

The text of this document points implicitly to an “incomplete” Christianization of Europe before the Reformation — an possibility substantiated in historical works by scholars like Jean Delumeau, especially Le Catholicisme entre Luther et Voltaire (1971). Many pre-Christian beliefs and traditions persisted in the popular Latin Christianity of the fifteenth-century, some of which were shared in elite populations as well. Most English people maintained some belief in both white magic and its opposite, maleficium (which we usually translate, a bit loosely, as sorcery), and many might have taken resort in popular magic as a way of dealing with their world through charms, potions, or amulets, but trials for maleficium were rare and punishments for the convicted remained light throughout the Middle Ages.

***

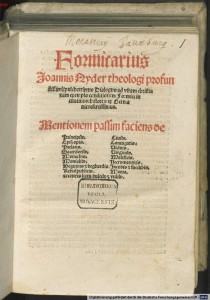

[Right: Title page of Nider’s Formicarius (this edition, Cologne 1506), a copy that belonged at some point to a monastery, made its way to the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, and has now been digitalized. Source of image — follow the link and you can page through the book.]

***

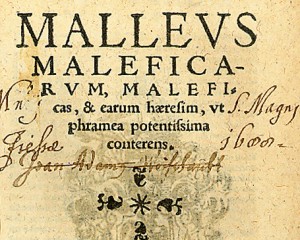

This state of affairs was changing after the mid-thirteenth century, a point at which heresy prosecutions in general were on the rise, and reached a critical point in the fifteenth century, as growth of learned knowledge about the supernatural world caused educated men to seek out evidence of their discoveries in the world around them. Traditions of elite magic grew and intensified among clerics, and as they did, scholars sought to connect these to popular practices. (We’ll look at elite magic — more closely associated with wands than the popular traditions that preceded the fifteenth century — in one of the final posts in this series.) Two learned works of the fifteenth century, Johannes Nider’s Formicarius and Heinrich Sprenger’s Malleus maleficarum, played important roles in convincing learned men to turn against the late medieval consensus, arguing that witchcraft was not a delusion on the part of the observer, but real and efficacious. Nider’s work, written in the 1430s but first published in 1475, was the first to argue that the true threat of witchcraft came not from elite necromancers, but from uneducated females; Malleus maleficarum (1486) argued that witchcraft or belief in its effects were not delusions that reflected the loss of faith on the part of the believer, but rather actually occurring activities with real effects conducted by people who had consciously allied with the Devil for this purpose.

[Left: Section of title page of Malleus maleficarum (edition of Cologne 1520. This one’s in Sydney, Australia. Source.]

***

In reading these works, of course, it’s important to keep in mind that at the time of their publication, they were prescriptive rather than descriptive. Nider had to convince his audience that female witches were a greater threat than learned male magicians; Malleus maleficarum attempts to persuade clergymen and other authorities to look for evidence of maleficium in the world around them and act against it rather than turning a blind eye. These authors were less recounting a popular attitude than trying to prescribe what it should be; nonetheless, their influence means that by the time Shakespeare was writing, in any case, elements of their worldview were generally shared by elite and popular minds alike. In Part II, question 2, ch. 3, Malleus describes “inflammation with inordinate love” as “the best known and most general form of witchcraft.” So Edward IV could have been bewitched by Elizabeth Woodville — as the authors of Titulus Regius had argued he was. In Part II, question 1, ch. 5, Malleus states that witches have six ways of harming humans, among them “to cause some disease in any of the human organs … to take away life.” So Richard’s injuries as he describes them could have been caused by witchcraft.

What would an expert have told him to do? Malleus maleficarum does not leave the reader alone with the problem of maleficium. It recommends remedies; interestingly, in doing so, by distinguishing between lawful and unlawful ones, it gives us a sense of the entire range of things that people might have been inclined to do. The first thing the afflicted should not do is resort to a counter-maleficium of any kind, an index to the authors’ fear that this is the first thought someone might have. Because the authors argue throughout that sorcery is real, they must concede that such remedies could be effective — but in their association with the Devil, they were not permitted to Christians. On the matter of responding to inordinate love, Malleus notes that some of it is not due to witchcraft, and that ancient authors offered varying suggestions for dealing with it but then asks, “what use is it to speak of remedies to those who desire no remedy?” (P. II, q. 2, ch. 3). (I daresay that was Edward’s problem.) In the main, however, it suggests five remedies (P. II, q.2, ch. 2): “a pilgrimage to some holy and venerable shrine; true confession of sins with contrition; the plentiful use of the sign of the Cross and devout prayer; lawful exorcism by solemn words … and … a remedy can be affected by prudently approaching the witch.” In recommending that the victim simply ask the witch to stop, Malleus again concedes the primacy of the supernatural and the possibility that maleficium could win out if not opposed.

What would an expert have told him to do? Malleus maleficarum does not leave the reader alone with the problem of maleficium. It recommends remedies; interestingly, in doing so, by distinguishing between lawful and unlawful ones, it gives us a sense of the entire range of things that people might have been inclined to do. The first thing the afflicted should not do is resort to a counter-maleficium of any kind, an index to the authors’ fear that this is the first thought someone might have. Because the authors argue throughout that sorcery is real, they must concede that such remedies could be effective — but in their association with the Devil, they were not permitted to Christians. On the matter of responding to inordinate love, Malleus notes that some of it is not due to witchcraft, and that ancient authors offered varying suggestions for dealing with it but then asks, “what use is it to speak of remedies to those who desire no remedy?” (P. II, q. 2, ch. 3). (I daresay that was Edward’s problem.) In the main, however, it suggests five remedies (P. II, q.2, ch. 2): “a pilgrimage to some holy and venerable shrine; true confession of sins with contrition; the plentiful use of the sign of the Cross and devout prayer; lawful exorcism by solemn words … and … a remedy can be affected by prudently approaching the witch.” In recommending that the victim simply ask the witch to stop, Malleus again concedes the primacy of the supernatural and the possibility that maleficium could win out if not opposed.

***

When reading these sources, I’m always tempted to wonder whether the authors considered the possibility that in their remedies to witchcraft, they had embraced exactly the position they had hoped to eradicate. On the question of Richard’s arm, the solutions proposed by Malleus (P. II, q. 2, ch. 6) are rather more severe: only an exorcism will do. Because the procedure described is rather complicated, I’ll take up that topic on in the next post. However, I’ll leave you with a cliffhanger: in discussing the definition of an exorcist, the authors of Malleus call exorcists “lawful enchanters.” Thus, the remedies we can expect to have recommended bear a startling resemblance to the ills that caused them — a resemblance that the authors themselves concede.

***

If you’re interested, Malleus maleficarum is easy to obtain in modern translation; it’s both readable and gruesomely entertaining. The most widely available English translation, published by Montague Summers, is at best serviceable — Summers was a charlatan and the notes and ‘scholarly apparatus’ attached his editions are a mixture of uselessness and nonsense. A better translation with the most up-to-date approach to the scholarship — the one I make my students use — is Christopher Mackay’s Hammer of Witches (2009).

If you’re interested, Malleus maleficarum is easy to obtain in modern translation; it’s both readable and gruesomely entertaining. The most widely available English translation, published by Montague Summers, is at best serviceable — Summers was a charlatan and the notes and ‘scholarly apparatus’ attached his editions are a mixture of uselessness and nonsense. A better translation with the most up-to-date approach to the scholarship — the one I make my students use — is Christopher Mackay’s Hammer of Witches (2009).