Sources Sunday: Thomas More’s History of King Richard III

See series introduction, here.

***

Today, I’d like to introduce briefly one of the earlier secondary sources about Richard III, a text written by Thomas More called The History of King Richard III. No matter how you feel about Richard, it’s a cracking read, and the late historian Richard Marius called it “the finest thing he ever wrote.” Even Ricardian biographer Paul Murray Kendall called the work an expression of More’s “stunning vitality.” Here are some things to keep in mind when reading this work.

***

This got really long, so I’ll limit myself to these introductory remarks this week and start talking about specific citations next time.

***

The source itself

- More worked on this text between 1513 and 1518 in Latin and English simultaneously, and never finished it. His English narrative stops at the beginning of Buckingham’s rebellion; his Latin narrative, somewhat earlier, at Richard’s coronation.

- Modern textual scholars believe that More composed the Latin and English versions of the text separately, transferring bits and pieces between them, so that neither text by itself is considered fully authoritative.

- No original of More’s text in his own handwriting (any so-called holograph) survives either in Latin or in English.

- The text was not published in More’s lifetime, possibly because he became too busy to finish it; or because he realized that the matters treated in the text involved too many people who were still alive, so that the appearance of the work would create political problems for him.

- No English manuscript sources survive; several Latin manuscript sources survive, but these are reworkings of the original holograph based on copies that themselves have disappeared in the meantime. The most well-known of the surviving Latin manuscripts — all of which differ — are held at Paris in the Bibliothèque nationale (MS fr. 4996 [Ancien fonds]), and at London in the College of Arms (MS Arundel 43) and the British Library (MS Harley 902). Here’s an excellent technical summary of the transmission of the texts with diagrams. Now considered to provide most authoritative Latin version, the Paris manuscript was rediscovered, entirely by accident, only in the twentieth century, by More scholar Daniel Kinney.

- The “critical edition” of the texts — the definitive version scholars consider closest to the original, which should be used by all researchers — is The Complete Works of St. Thomas More, 15 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963-97).

- Most modern versions of the text produced for general readers or students are emended on the basis of the 1557 London edition: William Rastell, ed., The workes of Sir Thomas More Knyght […]. This was not the first English printing of the text, but it has long been considered the most authoritative as it seems to have been typeset from a no-longer-extant holograph. (Rastell was More’s nephew.)

***

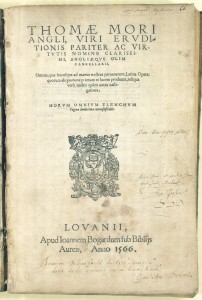

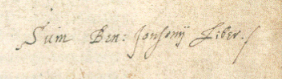

[Right: Titlepage of the 1566 Louvain edition of Thomas More’s works; picture taken from the copy owned by Ben Jonson, the English playwright Ben Jonson. Source.]

[Left: detail of above, with inscription: “Sum Ben: Jonsonij Liber.”; literally, “I am Ben Johnson’s book.” Further inscriptions on the title page reveal that Johnson gave the book to William Dakins, one of the men who translated the King James Bible, whom Jonson probably met at Westminster School. Dakins, in turn, gave it with an inscription to John Blumfeilde.]

[Left: detail of above, with inscription: “Sum Ben: Jonsonij Liber.”; literally, “I am Ben Johnson’s book.” Further inscriptions on the title page reveal that Johnson gave the book to William Dakins, one of the men who translated the King James Bible, whom Jonson probably met at Westminster School. Dakins, in turn, gave it with an inscription to John Blumfeilde.]

***

On More

- More was an extraordinarily talented, intelligent, and complex individual.

- His most prominent intellectual friendship was with Erasmus of Rotterdam, who wrote a hilarious persiflage on the folly of life in general and the abuses of the Catholic Church in particular known as Encomium Moriae, or “In Praise of Folly,” which punned on More’s name (the Greek word for “folly” sounded similar to More’s name).

- Although he became an influential politician and lawyer, and remained a layman, he seriously contemplated a career in the Church.

- In his own age, he was notable for the attention he paid to his daughters’ education.

- The most definitive intellectual influence on More’s writing was that of Renaissance humanism; yet, after he joined the service of King Henry VIII in 1518, he ceased almost completely to write humanist texts and turned to religious polemics.

- Modern readers may know him best for his 1516 work, Utopia (he coined the term).

- More enjoys a reputation as a staunch man of principle, but not always a pleasant one. On the one hand, as Chancellor of England, he vigorously persecuted and prosecuted Protestant heretics. Six were burned on his watch. His polemics against William Tyndale were influential in the latter’s eventual burning for heresy; and George Foxe, who cataloged the sufferings of Protestant martyrs in England, was convinced that More had personally tortured prisoners on trial for heresy. On the other, More has long been respected for his conviction that authority over Church matters should not be ceded to the secular government, as a consequence of which he was executed in 1535 for his refusal to take the 1534 Oath of Supremacy. Was he moral, or a moralist? The twentieth century tended to see him as moral (as in the much celebrated stage and screen drama, The Man for All Seasons), while more recently, in Wolf Hall (2009), for which she won the Booker Prize, Hilary Mantel has portrayed him as a petty, cruel tyrant.

***

[Right: Paul Scofield as Thomas More, insisting to Parliament that he has not committed treason, in the film version of A Man for All Seasons. Scofield won the Oscar for Best Actor in 1966 for this performance and a BAFTA as well. Source.]

[Right: Paul Scofield as Thomas More, insisting to Parliament that he has not committed treason, in the film version of A Man for All Seasons. Scofield won the Oscar for Best Actor in 1966 for this performance and a BAFTA as well. Source.]

***

***

***

General features of More’s history of Richard

- More probably chose Richard as a topic because of his interest in politics and good government. The book is a foil to Utopia (1516), which discusses perfect government and decries amorality in politics; More saw Richard as the epitome of bad, because amoral, government.

- Humanists saw the point of history as teaching life lessons (historia magistra vitae); despite his many dastardly individual features, Richard in More’s eyes was much more a negative example or pattern rather than a fully formed individual. While More clearly believed what he wrote of Richard to be true, the goal was neither a smear job nor the presentation of evidence about Richard’s reign, but rather the crafting of a tale that criticized amorality, hypocrisy, and vaulting ambition.

- According to scholar George M. Logan, the most important influences on More’s structuring of his history are the Greek author Lucian and the Roman historians Sallust (who wrote histories of the Roman traitors Catiline and Jugurtha) and Tacitus (who wrote a history of the Roman emperor, Tiberius). So great is More’s admiration of Tacitus that he alters facts in his portrayal of Edward IV in order to make his reign seem more like that of Augustus.

- We cannot see More as a straightforward Tudor propagandist; he despised Henry VII.

- More’s history counts as a secondary source in that he did not witness the events he describes. He did draw on primary sources: oral information and reminiscences of people he knew who had lived through events. These included his father (the only source he explicitly names), but more importantly gossip in the household of Bishop John Morton, one of Edward IV’s officials implicated in Hastings’ conspiracy, who survived Richard’s reign. More served in Morton’s household he served as a page from 1490-2.

- While as a public official, More could have consulted extant public records in London, textual comparison suggests that he seems to have done so only once (for Buckingham’s speech of June 26, 1483).

- Though it is extremely unlikely that More knew the work of the second Croyland Continuator, which was unknown outside of its abbey until the later sixteenth century, his account squares with it in important details, another reason to discount the charge that More (or Croyland) were mere Tudor propagandists.

- The only written historical works that More can be proven to have consulted are Fabyan’s New Chronicles of England and France (1516/7) and Great Chronicle of London (ms., 1512).

- No textual evidence suggests that the work on Richard most typically cited as Tudor propaganda, Polydore Vergil’s Anglica historia (ms. 1513), was influential on More.

- The conventions of Renaissance humanist historiography required More to concoct all of the speeches; readers at the time would have known this.

- More’s most prominent literary and linguistic device throughout the work is irony; readers must thus be very careful to discern his meaning, since his words are frequently pointed in specific ways.

- Although the text was one of the most popular works of history in later-sixteenth-century England, it had little influence on history-writing. It made its deepest impact, of course, on Shakespeare, which is the main reason a reader might care about it these days.

- Richard Marius makes the interesting assertion that Richard III is one of the first hypocritical protagonists in the history of western literature.

Further reading

Further reading

- Read More’s History of King Richard III on the web, transcribed from the original English edition of 1557 (with original spelling, but modern typography) here.

- If you like books and ready-to-use scholarship, a fantastic update with extensive notes and sixteenth-century usage retained, but modified to reflect modern spelling, has recently been produced: George M. Logan, ed., The History of Richard III: A Reading Edition (Bloomington: Indianapolis University Press, 2005). This is the one my students will be reading.

- Read More’s history in Latin, in the edition that English playwright Ben Jonson used with his notes visible in the margin, at The Center for Thomas More Studies, in digital facsimile.

- Read More’s others works at Center for Thomas More Studies at the University of Dallas as well.

- Richard III Society resources on More’s history, including excerpts from relevant pieces of Marius’ biography, Thomas More: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1984). (Marius’ biography of More is excellent — a much better work than his disappointingly partisan biography of Martin Luther.)

***

If that’s not too much — I’ll be back next week to discuss some of the fascinating points in More’s retelling of Richard’s story.

Sources Sunday: Introduction

Today I’ll be starting a new feature on King Richard Armitage (to appear as regularly as I can manage), called “Sources Sunday.” In these posts, I’ll look in detail at excerpts from the sources used to write the life and times of Richard III in the last half millennium. I’ll explain their contexts and meanings, and consider the ways in which historians have understood them in the past and how we might look at them today.

***

Couple things to start off — probably elementary for most readers:

- We historians are “source geeks” and “archive rats.” Before we make claims, we like to have evidence. We get our evidence from sources. A source can be anything that we can all examine. The most frequent sources historians use are texts, documents, or material objects, or, in modern history, interviews, photographs, or films and recordings. Sometimes sources disappear entirely, or over long intervals — in those cases, we look at records of those sources as available.

- Historians conventionally divide between primary and secondary sources (although this division is not a strict one). Primary sources stem from the immediate surroundings of the events they capture and include reports by eyewitnesses, recordings, artifacts, and so on. Secondary sources, in contrast, build upon primary sources to provide their accounts of historical matters. Historians concentrate on identifying primary sources for their accounts, although they are not inherently more accurate than secondary sources.

- Ideally, a historian hopes to examine many primary sources. One of the big problems in writing a biography of Richard is that so many primary sources either never existed or have not survived, particularly those that might answer questions that interest us most, so that the first secondary sources, which were negative to Richard, became disproportionately influential.

- Comparing information from different sources allows us to come to judgment about the past. A judgment about the past is more secure, the more often it is corroborated by independent sources (ones that do not simply repeat each other’s claims). Thus we talk about and critique the transmission of particular chains of evidence from source to source. Where a source does not speak, most historians prefer to state that no conclusion can be drawn.

- No source is neutral, just as no history is neutral. Every source, every history, takes a point of view. It’s part of the historian’s job to discern and understand the source’s point of view in order to explain how that affects the information the source gives us. We call this process of assessing the reliability of a source, “source critique.”

- In order to produce a source critique, or explain how information from sources is produced and presented, working historians use a “method” or “methods”; that is, we follow particular rules for drawing conclusions from certain kinds of sources. A method is adapted to its particular kind of source (we use textual methods on texts; mathematical methods on tax records; archaeological methods on bones — and so on). Different methods, when used appropriately, can allow us to see different elements in the same sources — it’s a bit like looking at an object under a UV light vs infrared light vs normal daylight. Similarly, a method will tell us what questions cannot be answered from a particular source.

***

Finally, the point of these posts isn’t to support or refute the case for or against Richard III. Rather, it’s to try to understand the points of view held by the people most responsible for creating his reputation in the last five centuries. In understanding the sources about Richard better, we can come to understand his age and the factors that shaped him — and the people who have written about him — more effectively.

Fifteenth-century remedies against witchcraft, part 2

***

Wishing those who marked these days — belatedly — a meaningful All Souls’ Day and Día de los muertos! I miss living more directly in the Mexican diaspora and hope that anyone who had access to one ate a piece of pan de muerto in my honor (picture at right; source).

Wishing those who marked these days — belatedly — a meaningful All Souls’ Day and Día de los muertos! I miss living more directly in the Mexican diaspora and hope that anyone who had access to one ate a piece of pan de muerto in my honor (picture at right; source).

***

Turning to England, I was alerted this morning that the BBC HistoryExtra currently offers a quiz to determine whether you would have been accused of witchcraft. It’s well-constructed, if a bit simplistic, and based on the information I gave, I would have been accused. (Hmmm. And it’s not because I’ve read the Malleus maleficarum repeatedly.) There’s also a podcast on the significance of the Plantagenets to British history, which I am downloading for later. Apropos of Plantagenets, Sharon Kay Penman noted, on her fan club facebook page (you must join to see), that today marks the anniversary of the birth of the ill-fated Edward V and his younger sister, Anne.

[Left: The surviving main building at the abbey of Cluny, where Abbot Odilo originated the celebration of All Souls’ Day in the early eleventh century. The spread of the celebration of this holiday is associated with growing belief in the doctrine of purgatory in the western church after the mid-tenth century. Source.]

[Left: The surviving main building at the abbey of Cluny, where Abbot Odilo originated the celebration of All Souls’ Day in the early eleventh century. The spread of the celebration of this holiday is associated with growing belief in the doctrine of purgatory in the western church after the mid-tenth century. Source.]

***

King Richard Magic Week continues below. Check out posts on the witchcraft’s threat to the crown in the fifteenth century, Gloucester’s witchcraft accusations in Richard III, and elite remedies against witchcraft.

***

Part II, question 2, ch. 6, of Malleus maleficarum, where exorcism to end bewitchment is discussed, is extraordinarily rich. A complete interpretation of it would explode the bounds of a single post. For instance, it treads perilously close to heresy several times — by proposing a remedy for witchcraft that is prohibited by canon law and was illegal in civil codes at the time in much of continental Europe (rebaptizing the victim); by charging that a priest in a state of grace is a more effective practitioner of an exorcism than a sinful one (a loophole may be that although the belief that a priest must be in a state of grace to perform a sacrament is heretical, exorcism is not a sacrament); and by suggesting that some baptisms were not effective the first time (clearly heretical because the sacraments work ex opere operato). But we’re interested in magic, not in heresy, here!

I noted in the previous post that the only remedy the Malleus maleficarum offers against witchcraft affecting the body is exorcism: the ritual or verbal casting out of demons or the Devil. In understanding the recommendations, it is helpful to consider what fifteenth-century authors might have meant by exorcism — since the common picture in the minds of most people today comes from an infamous 1971 film. (Maybe not so infamous to younger viewers — a review by a fellow Richard Armitage blogger expresses some confusion about the fame of the film.) And although the rank of “exorcist” was a minor order of the Church, it means something different now than it did in the 1470s. Indeed, the work stresses that one must not have taken the order in order to perform an exorcism.

Having thus discounted the possibility that exorcism differs from witchcraft because of the clerical status of its practitioner, the authors must set up a means by which an afflicted person can judge whether any exorcism would be lawful. They write:

The clergy have become too slothful to use any more the lawful words when they visit the sick. On this account … such lawful exorcisms may be used by a religious and discreet priest, or by a layman, or even by a woman of good life and proved discretion; by the offering of lawful prayers upon the sick. … And such persons are not to be prevented from practicing it in this way; unless perhaps it is feared that, following their example, other indiscreet persons should make improper use of incantations.

If the practitioner is pious, the victim may obtain help. The authors then list seven conditions for judging the lawfulness of remedies offered by such people: (1) no explicit or implicit invocation of devils; (2) no unknown names in charms; (3) nothing untrue in the words / no doggerel; (4) no written characters besides the sign of the cross — the authors note that this provision condemns most charms carried by soldiers; (5) no requirements regarding the method of writing or binding the charm on the person’s body; (6) use of scripture or words of saints must rely on effect from divine virtue or the relics of the saints; (7) the effect must be left open to divine will. “If none of these conditions be broken,” the authors conclude, “the incantation will be lawful.” These conditions established, the authors continue to note that a charm fixed around the neck is effective if the person who wears it understands the words in the charm; but if not, “it is enough if such a man fixes his thoughts on the divine virtue.”

If these simple measures have no effect, further steps can be taken. The afflicted person should make a good confession. Then, “let a diligent search be made in all corners and in the beds and mattresses and under the threshold of the door, in case some instrument of witchcraft may be found … and … all bedclothes and garments should be renewed, and … he should change his house and dwelling.” If these things do not avail, the afflicted should go the church on a feast day, take a holy candle, and pray. Various sacramentals (stole, holy water) should be employed. This ritual should be followed three times a week until successful. The victim should also receive the Eucharist, but only if he has not been excommunicated. Finally, the beginning words of the Gospel of John (“In the beginning was the Word …”) should be written and hung around his neck. (This widespread remedy against demonic attack in extremis is frequently evidenced in sources concerning women in childbirth, into the mid-sixteenth century.)

The authors then discuss reasons why exorcism — which is not a sacrament, so it doesn’t work automatically — may not work. Most of these relate to want of faith or piety in the victim, those praying for the victim or the exorcist, but the authors also suggest that the remedy may be flawed. Therefore the authors cite a final remedy for stubborn cases: rebaptism:

“It is said … of those who walk in their sleep during the night over high buildings without any harm, that it is the work of evil spirits who thus lead them; and many affirm that when such people are rebaptized they are much benefited. And it is wonderful that, when they are called by their own names, they suddenly fall to earth, as if that name had not been given to them in proper form at their baptism.”

Finally, the authors conclude with a discussion of natural remedies — which probably would have been the first resort of many people who sought to counter black magic with white. “If natural objects are used in a simple way to produce certain effects for which they are thought to have some natural virtue,” the authors conclude, “this is not unlawful. But if there are joined to this certain characters and unknown signs and vain observations, which manifestly cannot have any natural efficacy, then it is superstitious and unlawful.”

***

In the attempt to understand fifteenth-century piety and religion, we could make several observations about this body of remedies.

First, we’re clearly dealing with a mostly illiterate society here — so the shape of marks is more important than letters; and the remedies are claimed to work even if the victim is too uneducated to understand the sense of the words being used — which makes scriptural words hardly indistinguishable from magical marks, and one wonders how most people might have made the distinction.

Second, in contrast to the sort of universalizing statements the Latin church had regularly made about itself since at least the beginning of the thirteenth century, dealing with witchcraft gives the victim little reliance on the Church. After baptism, which includes a brief formula and prayer of exorcism (Exorcizo te, immunde spiritus, in nomine Patris + et Filii + et Spiritus + Sancti, ut exeas, et recedas ab hoc famulo …), the church has no additional tool to cast out the devil automatically, only a ritual (exorcism) that is dependent on the faith of the victim and those supporting him in his ordeal. Along the same lines, the authors suggest repeatedly that the clergy may not necessarily offer any help — they are too lazy, or not in a state of grace, or not pious enough. I tend not to be a big fan of the scholarly argument that Europeans on the eve of the Reformation were constantly tortured by the imminence of damnation and that medieval piety did nothing against such fears — but depending on how we understand it, this discussion of exorcism offers some anchoring for that position, even if the Reformation — which is only thirty years in the future at this point — clearly expanded both fears and persecutions of sorcery of various types.

Finally, and decisively, the remedies proposed look from our perspective suspiciously like witchcraft themselves in that they both explicitly legitimate the practice of witchcraft by giving it credibility (if you’re suffering, look for an enchanted object that’s causing it), and by suggesting mechanisms (charms, language, contact with relics) strongly similar to those used by witches to cause enchantments in the first place. Baptism is supposed to call demons out of the body of the baptizand — but the discussion if its efficacy implies that it also give the baptizand a name by which he may be called, putting him in a parallel position to beings, like demons and spirits, that may be summoned. The authors of the work seem unaware of or uninterested in this relationship, a parallelism that suggests that they themselves were incorporated into the paradigm that made witchcraft accusations simply “make sense” in explaining the world.

***

And Shakespeare’s Gloucester? He could have undertaken any of these things — but, the implication is, he himself is so implicated in the disordered and unlawful relationships exemplified by witchcraft that he choose to wreak further havoc rather than dealing with them.

***

Calendar-wise, Magic Week 2012 is over, but I had two more subjects planned for this series. I will try to get to them this week. I’m also happy to answer questions if anything’s unclear.

Protecting Richard: Fifteenth-century remedies against witchcraft, part 1

***

King Richard Magic Week 2012 continues! I apologize for not posting on Halloween — Wednesday is a big teaching / office / service day for me. Happy Samhain to those who celebrated it and Happy All Saints’ Day to those celebrating that.

***

In the first post in this series, on the reality of witchcraft threats in early modern England, I argued that discussions of witchcraft need to be taken seriously on their own terms (as opposed to being understood as a symptom or reflection of something else). In the second post, on Gloucester’s witchcraft accusations in Shakespeare’s Richard III, I argued, given that Shakespeare can be assumed to share the beliefs of his age, Gloucester’s use of the witchcraft accusation against Elizabeth and Jane Shore is a way for the characters in the play and its audiences to account for the disorder of a political world in which Gloucester could accuse Hastings, historically one of his family’s most loyal supporters, with treason. Following on those two posts, given that witchcraft was real for Richard III’s contemporaries and that it was a factor for a century later in explaining the ills of politics gone wrong, as another means of talking about fifteenth-century ideas, I want to ask a hypothetical counterfactual. Assuming that Richard III had been beset by witchcraft, how could he have cured this situation?

In the first post in this series, on the reality of witchcraft threats in early modern England, I argued that discussions of witchcraft need to be taken seriously on their own terms (as opposed to being understood as a symptom or reflection of something else). In the second post, on Gloucester’s witchcraft accusations in Shakespeare’s Richard III, I argued, given that Shakespeare can be assumed to share the beliefs of his age, Gloucester’s use of the witchcraft accusation against Elizabeth and Jane Shore is a way for the characters in the play and its audiences to account for the disorder of a political world in which Gloucester could accuse Hastings, historically one of his family’s most loyal supporters, with treason. Following on those two posts, given that witchcraft was real for Richard III’s contemporaries and that it was a factor for a century later in explaining the ills of politics gone wrong, as another means of talking about fifteenth-century ideas, I want to ask a hypothetical counterfactual. Assuming that Richard III had been beset by witchcraft, how could he have cured this situation?

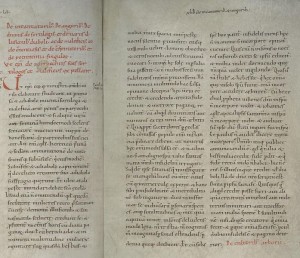

[Right: Canon episcopi in Hs. 119 (Cologne), a ninth-century passage in canon law on witchcraft beliefs. Source.]

***

Were we able to juxtapose Richard and Shakespeare, we would likely discover that Shakespeare, writing around 1591, was probably significantly more knowledgeable about witchcraft than Richard, who died over a century earlier, would have been. Richard lived in a watershed period for explaining and understanding witchcraft. Medieval monarchs and churchmen alike had been negative to skeptical about popular beliefs about the efficacy of witchcraft, which they associated with paganism, until approximately the mid-thirteenth century. Indeed, this skepticism had been incorporated into canon law via the text of Canon episocopi, a text that argued that people who believed in efficacious witchcraft were heretics who had lost their faith and succumbed to the Devil. The effects of witchcraft occurred in the imagination, not in physical reality.

The text of this document points implicitly to an “incomplete” Christianization of Europe before the Reformation — an possibility substantiated in historical works by scholars like Jean Delumeau, especially Le Catholicisme entre Luther et Voltaire (1971). Many pre-Christian beliefs and traditions persisted in the popular Latin Christianity of the fifteenth-century, some of which were shared in elite populations as well. Most English people maintained some belief in both white magic and its opposite, maleficium (which we usually translate, a bit loosely, as sorcery), and many might have taken resort in popular magic as a way of dealing with their world through charms, potions, or amulets, but trials for maleficium were rare and punishments for the convicted remained light throughout the Middle Ages.

The text of this document points implicitly to an “incomplete” Christianization of Europe before the Reformation — an possibility substantiated in historical works by scholars like Jean Delumeau, especially Le Catholicisme entre Luther et Voltaire (1971). Many pre-Christian beliefs and traditions persisted in the popular Latin Christianity of the fifteenth-century, some of which were shared in elite populations as well. Most English people maintained some belief in both white magic and its opposite, maleficium (which we usually translate, a bit loosely, as sorcery), and many might have taken resort in popular magic as a way of dealing with their world through charms, potions, or amulets, but trials for maleficium were rare and punishments for the convicted remained light throughout the Middle Ages.

***

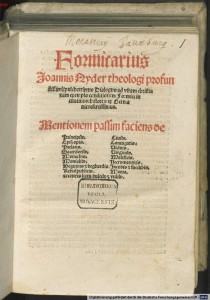

[Right: Title page of Nider’s Formicarius (this edition, Cologne 1506), a copy that belonged at some point to a monastery, made its way to the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, and has now been digitalized. Source of image — follow the link and you can page through the book.]

***

This state of affairs was changing after the mid-thirteenth century, a point at which heresy prosecutions in general were on the rise, and reached a critical point in the fifteenth century, as growth of learned knowledge about the supernatural world caused educated men to seek out evidence of their discoveries in the world around them. Traditions of elite magic grew and intensified among clerics, and as they did, scholars sought to connect these to popular practices. (We’ll look at elite magic — more closely associated with wands than the popular traditions that preceded the fifteenth century — in one of the final posts in this series.) Two learned works of the fifteenth century, Johannes Nider’s Formicarius and Heinrich Sprenger’s Malleus maleficarum, played important roles in convincing learned men to turn against the late medieval consensus, arguing that witchcraft was not a delusion on the part of the observer, but real and efficacious. Nider’s work, written in the 1430s but first published in 1475, was the first to argue that the true threat of witchcraft came not from elite necromancers, but from uneducated females; Malleus maleficarum (1486) argued that witchcraft or belief in its effects were not delusions that reflected the loss of faith on the part of the believer, but rather actually occurring activities with real effects conducted by people who had consciously allied with the Devil for this purpose.

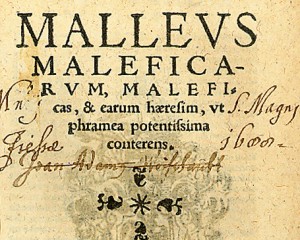

[Left: Section of title page of Malleus maleficarum (edition of Cologne 1520. This one’s in Sydney, Australia. Source.]

***

In reading these works, of course, it’s important to keep in mind that at the time of their publication, they were prescriptive rather than descriptive. Nider had to convince his audience that female witches were a greater threat than learned male magicians; Malleus maleficarum attempts to persuade clergymen and other authorities to look for evidence of maleficium in the world around them and act against it rather than turning a blind eye. These authors were less recounting a popular attitude than trying to prescribe what it should be; nonetheless, their influence means that by the time Shakespeare was writing, in any case, elements of their worldview were generally shared by elite and popular minds alike. In Part II, question 2, ch. 3, Malleus describes “inflammation with inordinate love” as “the best known and most general form of witchcraft.” So Edward IV could have been bewitched by Elizabeth Woodville — as the authors of Titulus Regius had argued he was. In Part II, question 1, ch. 5, Malleus states that witches have six ways of harming humans, among them “to cause some disease in any of the human organs … to take away life.” So Richard’s injuries as he describes them could have been caused by witchcraft.

What would an expert have told him to do? Malleus maleficarum does not leave the reader alone with the problem of maleficium. It recommends remedies; interestingly, in doing so, by distinguishing between lawful and unlawful ones, it gives us a sense of the entire range of things that people might have been inclined to do. The first thing the afflicted should not do is resort to a counter-maleficium of any kind, an index to the authors’ fear that this is the first thought someone might have. Because the authors argue throughout that sorcery is real, they must concede that such remedies could be effective — but in their association with the Devil, they were not permitted to Christians. On the matter of responding to inordinate love, Malleus notes that some of it is not due to witchcraft, and that ancient authors offered varying suggestions for dealing with it but then asks, “what use is it to speak of remedies to those who desire no remedy?” (P. II, q. 2, ch. 3). (I daresay that was Edward’s problem.) In the main, however, it suggests five remedies (P. II, q.2, ch. 2): “a pilgrimage to some holy and venerable shrine; true confession of sins with contrition; the plentiful use of the sign of the Cross and devout prayer; lawful exorcism by solemn words … and … a remedy can be affected by prudently approaching the witch.” In recommending that the victim simply ask the witch to stop, Malleus again concedes the primacy of the supernatural and the possibility that maleficium could win out if not opposed.

What would an expert have told him to do? Malleus maleficarum does not leave the reader alone with the problem of maleficium. It recommends remedies; interestingly, in doing so, by distinguishing between lawful and unlawful ones, it gives us a sense of the entire range of things that people might have been inclined to do. The first thing the afflicted should not do is resort to a counter-maleficium of any kind, an index to the authors’ fear that this is the first thought someone might have. Because the authors argue throughout that sorcery is real, they must concede that such remedies could be effective — but in their association with the Devil, they were not permitted to Christians. On the matter of responding to inordinate love, Malleus notes that some of it is not due to witchcraft, and that ancient authors offered varying suggestions for dealing with it but then asks, “what use is it to speak of remedies to those who desire no remedy?” (P. II, q. 2, ch. 3). (I daresay that was Edward’s problem.) In the main, however, it suggests five remedies (P. II, q.2, ch. 2): “a pilgrimage to some holy and venerable shrine; true confession of sins with contrition; the plentiful use of the sign of the Cross and devout prayer; lawful exorcism by solemn words … and … a remedy can be affected by prudently approaching the witch.” In recommending that the victim simply ask the witch to stop, Malleus again concedes the primacy of the supernatural and the possibility that maleficium could win out if not opposed.

***

When reading these sources, I’m always tempted to wonder whether the authors considered the possibility that in their remedies to witchcraft, they had embraced exactly the position they had hoped to eradicate. On the question of Richard’s arm, the solutions proposed by Malleus (P. II, q. 2, ch. 6) are rather more severe: only an exorcism will do. Because the procedure described is rather complicated, I’ll take up that topic on in the next post. However, I’ll leave you with a cliffhanger: in discussing the definition of an exorcist, the authors of Malleus call exorcists “lawful enchanters.” Thus, the remedies we can expect to have recommended bear a startling resemblance to the ills that caused them — a resemblance that the authors themselves concede.

***

If you’re interested, Malleus maleficarum is easy to obtain in modern translation; it’s both readable and gruesomely entertaining. The most widely available English translation, published by Montague Summers, is at best serviceable — Summers was a charlatan and the notes and ‘scholarly apparatus’ attached his editions are a mixture of uselessness and nonsense. A better translation with the most up-to-date approach to the scholarship — the one I make my students use — is Christopher Mackay’s Hammer of Witches (2009).

If you’re interested, Malleus maleficarum is easy to obtain in modern translation; it’s both readable and gruesomely entertaining. The most widely available English translation, published by Montague Summers, is at best serviceable — Summers was a charlatan and the notes and ‘scholarly apparatus’ attached his editions are a mixture of uselessness and nonsense. A better translation with the most up-to-date approach to the scholarship — the one I make my students use — is Christopher Mackay’s Hammer of Witches (2009).

“See how I am bewitch’d”: Interpreting witchcraft accusations in Shakespeare’s “Richard III’

***

King Richard’s Magic Week 2012 continues. The first post, on the significance of magic in the fifteenth century, is found here. My reading tip — if you want to plumb current scholarly understandings of what magic and witchcraft meant in the early modern context — and you’re not afraid of exposing yourself to some serious erudition — the book’s been described as “evocative and relentlessly academic” but also as “unrivalled” — I can make no more compelling recommendation than Stuart Clark’s Thinking with Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe (1999), upon which many of my insights and arguments about the intertwining of various strands of early modern life with witchcraft are drawn. I love this book; my copy is battered and worn.

In this post, I draw on Clark’s idea that witchcraft accusations were not a pretext for political moves, but rather understood by early modern people as an intimate factor in how politics actually worked.

***

In Act III, scene iv of Shakespeare’s Richard III, in an intriguing exchange, the character of Gloucester (Richard’s title before becoming king) attributes his physical deformity to the machinations of witches — specifically, his late brother Edward’s wife and Edward’s mistress, Jane Shore. After charging that they have sought his death with their “devilish plots,” he urges:

Then be your eyes the witness of this ill:

See how I am bewitch’d; behold mine arm

Is, like a blasted sapling, wither’d up:

And this is Edward’s wife, that monstrous witch,

Consorted with that harlot strumpet Shore,

That by their witchcraft thus have marked me.

Laying aside Shakespeare’s bias against Richard, as well as the debates over the status of his physique — although the language and image of a “blasted sapling” are compelling to me — the modern reader is likely to interpret this accusation as a political or misogynistic pretext for Richard’s rapaciousness. Such a reading seems at first to be supported by Gloucester’s declaration, in subsequent lines, that if Hastings is not willing to agree to this explanation, he must be a traitor:

“If! Thou protector of this damned strumpet–

Tellest thou me of ‘ifs’? Thou art a traitor:

Off with his head!”

Gloucester appears, here, to accuse the women of witchcraft as an excuse to eliminate anyone who disagrees with his usurping power grab.

Hastings’ intermediate line, however, tends to balance this reading with evidence of a worldview that attributed misfortunes to supernatural influences; Hastings does not say, “there are no witches,” or “witches don’t do things like that,” or even, “don’t accuse these women of being witches,” but rather, “If they have done this thing […] –” a line that explicitly concedes that witches exist who accomplish such deeds, though Gloucester cuts Hastings off, and we don’t get a “then” from him. This interpretation gains more currency when we consider that Shakespeare lacked access to Titulus Regius, the document that formulated the charge of witchcraft against Woodville and her mother — Henry VII had ordered all copies of it in English archives destroyed in order to protect his wife against the claims of illegitimacy that had justified the deposition of her younger brother, and our modern awareness of it postdates Richard III — and must have had another source, which points to a cultural willingness to associate Woodville with witchcraft. Finally, when we think about this scene in the context of political history, we note that the elimination of Hastings — who was supposed to have been in league with Elizabeth Woodville to keep her son, Edward V, on the throne, with the infamous Shore, also his mistress, as go-between for the conspirators — constituted a key step in Richard’s move toward the throne. But Hastings had made important sacrifices for the York family in the past, going into exile with Edward and Richard, and supporting Richard’s role as Lord Protector against the Woodvilles. In light of these political circumstances, of which the playwright was certainly aware, I suggest that Shakespeare does not have Gloucester accuse the women of witchcraft in order to present him as scheming to achieve his ends. Rather, Gloucester’s accusation in the play reflects his conviction that if something is troubling in his body or his political circumstances, then there must be an explanation — witches.

Hastings’ intermediate line, however, tends to balance this reading with evidence of a worldview that attributed misfortunes to supernatural influences; Hastings does not say, “there are no witches,” or “witches don’t do things like that,” or even, “don’t accuse these women of being witches,” but rather, “If they have done this thing […] –” a line that explicitly concedes that witches exist who accomplish such deeds, though Gloucester cuts Hastings off, and we don’t get a “then” from him. This interpretation gains more currency when we consider that Shakespeare lacked access to Titulus Regius, the document that formulated the charge of witchcraft against Woodville and her mother — Henry VII had ordered all copies of it in English archives destroyed in order to protect his wife against the claims of illegitimacy that had justified the deposition of her younger brother, and our modern awareness of it postdates Richard III — and must have had another source, which points to a cultural willingness to associate Woodville with witchcraft. Finally, when we think about this scene in the context of political history, we note that the elimination of Hastings — who was supposed to have been in league with Elizabeth Woodville to keep her son, Edward V, on the throne, with the infamous Shore, also his mistress, as go-between for the conspirators — constituted a key step in Richard’s move toward the throne. But Hastings had made important sacrifices for the York family in the past, going into exile with Edward and Richard, and supporting Richard’s role as Lord Protector against the Woodvilles. In light of these political circumstances, of which the playwright was certainly aware, I suggest that Shakespeare does not have Gloucester accuse the women of witchcraft in order to present him as scheming to achieve his ends. Rather, Gloucester’s accusation in the play reflects his conviction that if something is troubling in his body or his political circumstances, then there must be an explanation — witches.

Applying Clark to Shakespeare generates the following possible reading: One of the most common perversions associated with sorcery in the period was the distortion of love — and Richard should have loved Hastings. And yet he does not — which suggests something larger in the world of the play is amiss. While it’s clear that Shakespeare doesn’t much like Gloucester, this scene suggests that Gloucester is not so much evil because he lies — rather, he lies because everything around him, from his body to his ambitions, is permeated with demonic influences. In response, Richard, who reveals here that he’s quite conscious of this state of affairs, does not react against the influence of witches, but indeed cooperates with it. Richard, for Shakespeare, is thus much more than simply a usurper and a schemer — his usurpation and schemes are symptomatic of a political world gone wrong under the influence of supernatural forces.

Applying Clark to Shakespeare generates the following possible reading: One of the most common perversions associated with sorcery in the period was the distortion of love — and Richard should have loved Hastings. And yet he does not — which suggests something larger in the world of the play is amiss. While it’s clear that Shakespeare doesn’t much like Gloucester, this scene suggests that Gloucester is not so much evil because he lies — rather, he lies because everything around him, from his body to his ambitions, is permeated with demonic influences. In response, Richard, who reveals here that he’s quite conscious of this state of affairs, does not react against the influence of witches, but indeed cooperates with it. Richard, for Shakespeare, is thus much more than simply a usurper and a schemer — his usurpation and schemes are symptomatic of a political world gone wrong under the influence of supernatural forces.

***

Could he have reacted against demonic influence? Had Richard’s political and personal ends been fouled by witchcraft, could he have done anything about it? Yes, indeed — he could have. Seeing as how this is getting long, again, however, I’ll go to that theme in my next post, which will concern recommended fifteenth-century remedies against witchcraft.

Was Richard III really threatened by witchcraft?

***

***

On October 31, the northern hemisphere of Planet Earth finds itself halfway between autumnal equinox and winter solstice. In this week of the solar year, depending on our relationship to various western traditions, the supernatural and the related proximity of our own world to the souls of the dead may touch lightly or rest heavily on our minds. Celebrations and commemorations include Samhain, Halloween, All Saints’ / All Hallows, All Souls’, Día de los muertos, and probably a few more I’m not aware of. While contemporary commercialism amplifies our awareness of some of these holidays, at the same time, they have been associated with the themes of religion, magic, and witchcraft at least since the Celts. This week on King Richard Armitage, we’ll take a combination of historical, cultural, literary, fanciful and humorous approaches to the connections between Richard III and the supernatural realm.

On October 31, the northern hemisphere of Planet Earth finds itself halfway between autumnal equinox and winter solstice. In this week of the solar year, depending on our relationship to various western traditions, the supernatural and the related proximity of our own world to the souls of the dead may touch lightly or rest heavily on our minds. Celebrations and commemorations include Samhain, Halloween, All Saints’ / All Hallows, All Souls’, Día de los muertos, and probably a few more I’m not aware of. While contemporary commercialism amplifies our awareness of some of these holidays, at the same time, they have been associated with the themes of religion, magic, and witchcraft at least since the Celts. This week on King Richard Armitage, we’ll take a combination of historical, cultural, literary, fanciful and humorous approaches to the connections between Richard III and the supernatural realm.

***

***

Common wisdom discounts the preoccupation of the late medieval and early modern worlds with supernatural matters as the product of deficient knowledge. People acquainted with science, the story goes, reject magic. Most current professional historical scholarship rejects that view, pointing out the persistence of the irrational in contemporary life, but however we feel about their reasons, Richard III and his contemporaries lived in a world permeated with supernatural influences and occurrences. In that world, the miracle of the Eucharist — in which the communion host was transubstantiated by the words and actions of a priest into the actual, physical body of Jesus Christ — counterposed the manifestations of the Devil seen all around in disease, crop failures, and misfortunes great and small. The learned magician and the untutored witch or cunning woman acted as counterparts to the priest in offering people a chance to interact actively with the supernatural. Spells, charms, potions, and amulets as well as sacraments, rituals, and sacramentals offered technologies not only for explaining their circumstances, but influencing them.

Because most of us no longer believe in magic or witchcraft, we may tend to read their regular appearance in the political dramas of English history as pretext. On this view, people accused enemies of witchcraft in order to eliminate them, which could be said to explain why Shakespeare, whose Richard III was heavily influenced by propagandists sympathetic to the Tudor monarchs, was so willing to take up stories we today find politically motivated because we can’t imagine anyone believed them. But such views are anachronistic in light of the near-total absence of religious skepticism in Europe before the mid-seventeenth century. Shakespeare, too, probably believed in witchcraft, magic, and prophecy, along with his audiences — not only the plot, but also the appeal, of Macbeth are hard to understand without such sympathies. Moreover, accusations of undue supernatural influence would have carried little political weight had they been widely seen solely as pretexts. Contemporaries did not choose between witchcraft OR politics to explain situations they did not like, but rather saw them as intertwined. Bad politics was the result of evil manipulation of the supernatural.

Because most of us no longer believe in magic or witchcraft, we may tend to read their regular appearance in the political dramas of English history as pretext. On this view, people accused enemies of witchcraft in order to eliminate them, which could be said to explain why Shakespeare, whose Richard III was heavily influenced by propagandists sympathetic to the Tudor monarchs, was so willing to take up stories we today find politically motivated because we can’t imagine anyone believed them. But such views are anachronistic in light of the near-total absence of religious skepticism in Europe before the mid-seventeenth century. Shakespeare, too, probably believed in witchcraft, magic, and prophecy, along with his audiences — not only the plot, but also the appeal, of Macbeth are hard to understand without such sympathies. Moreover, accusations of undue supernatural influence would have carried little political weight had they been widely seen solely as pretexts. Contemporaries did not choose between witchcraft OR politics to explain situations they did not like, but rather saw them as intertwined. Bad politics was the result of evil manipulation of the supernatural.

Seen from this perspective, sorcery posed a serious threat to the English throne in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Henry IV’s wife, Joan, was imprisoned at the accusation of her stepson (the future Henry V) for using witchcraft — which explained her problematic influence, as “French,” at a time when Henry V was trying to reassert claim on the throne of France. Henry VI became the object of a plot by Eleanor Cobham, Duchess of Gloucester, when her own husband became heir presumptive — she consulted astrologers who predicted illness for Henry, and purchased potions, allegedly to help it along. When Henry heard this story, he also consulted astrologers — so the maleficence here involves not the use of the supernatural, but rather the malefactor’s impulses. Underlining the absolute normality with which everyone involved acted, Eleanor’s fellow accused were a cleric / learned astronomer, her personal confessor (i.e., a priest), and her personal physician (also a beneficed cleric), along with a witch who came from the ranks of the prosperous yeomanry and frequented the Gloucester court. Everyone except the witch was highly educated and all of them were acting in ways that everyone at the time understood.

Seen from this perspective, sorcery posed a serious threat to the English throne in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Henry IV’s wife, Joan, was imprisoned at the accusation of her stepson (the future Henry V) for using witchcraft — which explained her problematic influence, as “French,” at a time when Henry V was trying to reassert claim on the throne of France. Henry VI became the object of a plot by Eleanor Cobham, Duchess of Gloucester, when her own husband became heir presumptive — she consulted astrologers who predicted illness for Henry, and purchased potions, allegedly to help it along. When Henry heard this story, he also consulted astrologers — so the maleficence here involves not the use of the supernatural, but rather the malefactor’s impulses. Underlining the absolute normality with which everyone involved acted, Eleanor’s fellow accused were a cleric / learned astronomer, her personal confessor (i.e., a priest), and her personal physician (also a beneficed cleric), along with a witch who came from the ranks of the prosperous yeomanry and frequented the Gloucester court. Everyone except the witch was highly educated and all of them were acting in ways that everyone at the time understood.

Finally, the example most likely to interest Richard III fans: Elizabeth Woodville, accused of maneuvering Edward IV into marriage by witchcraft in Titulus Regius, the parliamentary document that declared her sons illegitimate and permitted Richard to take the crown is said in this text to have achieved this result by means of witchcraft accomplished with her mother as “the publique voice and fame is thorough all this Land.” In other words, in the troubled years of Edward’s reign, when tension over favors granted to the Woodvilles promoted a factionalism threatening to the peace of the realm, which a French marriage might have prevented, everyone had already spoken of the possibility that this was the case. Elizabeth was not a villain who was accused of witchcraft to discredit her influence. Rather, the document suggests, she had engaged in witchcraft, as a consequence of which she obtained an influence over Edward that brought ruin to the country, which meant that she was a villain. Such associations would have been obvious not least because love potions were a central part of the stock in trade of witches and cunning women — sought out by people of all ranks — so that Elizabeth’s personal attractiveness to Edward could also be explained with reference to witchcraft.

Finally, the example most likely to interest Richard III fans: Elizabeth Woodville, accused of maneuvering Edward IV into marriage by witchcraft in Titulus Regius, the parliamentary document that declared her sons illegitimate and permitted Richard to take the crown is said in this text to have achieved this result by means of witchcraft accomplished with her mother as “the publique voice and fame is thorough all this Land.” In other words, in the troubled years of Edward’s reign, when tension over favors granted to the Woodvilles promoted a factionalism threatening to the peace of the realm, which a French marriage might have prevented, everyone had already spoken of the possibility that this was the case. Elizabeth was not a villain who was accused of witchcraft to discredit her influence. Rather, the document suggests, she had engaged in witchcraft, as a consequence of which she obtained an influence over Edward that brought ruin to the country, which meant that she was a villain. Such associations would have been obvious not least because love potions were a central part of the stock in trade of witches and cunning women — sought out by people of all ranks — so that Elizabeth’s personal attractiveness to Edward could also be explained with reference to witchcraft.

***

***

And yes — a Richard III film will have to deal with this complex of themes. How were the different types of the supernatural tied together in the fifteenth century? So the answer to my question — was Richard III really threatened by witchcraft? — is: Yes. Because everyone in the fifteenth century was. They knew they were; beliefs in such matters were not excuses for other, less polite sentiments, or the refuge of the uneducated — they were matters that constituted the nature of temporal life just as certainly as gravity does for us. And the people who mattered in England for the previous century.

***

***

If Richard was indeed under threat from witchcraft, the question is what he could have done about it. I’ll pick up there in a future post. I actually wanted this one to be humorous, but I got preoccupied by reading Titulus Regius. Bl–dy Internet! Now that is an interesting document. So I may go there, next. Or not. Any preferences among the readership? Anything you want to know?