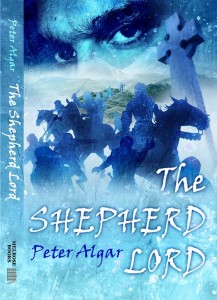

Interview with George Peter Algar,

author of The Shepherd Lord

David Santiuste (Historytimes.com)

In 1461 England was torn apart by civil war, as the rival houses of York and Lancaster battled for the throne. The Cliffords of Skipton, one of the most powerful families in Yorkshire, were committed Lancastrians. The head of the family, Lord John Clifford, was a formidable warrior – one of the most feared commanders of his day. But when Lord John was killed at the Battle of Towton he left his young son, Henry, to face the wrath of the vengeful Yorkists.

According to tradition, however, young Henry was sheltered by local common people. For many years, so the story goes, Henry lived incognito as a humble shepherd, earning himself a new title – the Shepherd Lord. But when Henry VII gained the throne, in 1485, Lord Henry Clifford was able to reclaim his birthright, returning to his family home.

The Shepherd Lord, by George Peter Algar, is a wonderful re-telling of this remarkable story. On the one hand, it is a tale of adventure, as Henry Clifford is hunted by the ruthless agents of King Edward IV. On the other, it is a tender story of coming-of-age, as Henry grows to manhood under the wise guidance of his protector, the shepherd Tom Lawkland. I was delighted to have the chance to talk to George, in order to find out more about his work.

I believe this is your first book. Why did you decide to write The Shepherd Lord?

I think it would be fair to say that this is a story that found me. I was idly leafing through a family history book, compiled by one of my American relatives, and came across a petition from a distant ancestor, Robert Bolling, to Edward IV, pleading for the return of his lands. Robert was attainted for his part in the support of the Lancastrian cause at the Battle of Towton. He claimed he was “oonly of Compulsion and by the most Drad Proclamation of John, then Lord Clifforde, under whose daunger and distresse the livelode of your seid suppliante lay” driven to support Henry VI. I thought , hang on, I don’t believe this for one moment, so I set out to prove the family’s Lancastrian sympathies. In doing so I came across the story of John Clifford’s son, the Shepherd Lord. I have always been keen on history and, as a proud Yorkshireman, knew a lot of our stories and legends but I have to admit to a feeling of great shame that I had not heard of this one.

What we had here was a story straight from the bible. Just who was the shepherd that had been entrusted with the safekeeping of John Clifford’s son? It set me thinking of Joseph, the surrogate father of Jesus, and just like the shepherd character, not much is written about poor old Joseph in the bible. He must have led an incredible life, but he was always second stage to the more glamorous characters on the scene. Then, we have the young, innocent Henry Clifford (the Shepherd Lord), ruthlessly hunted down by the Herod-like Edward IV. Then I read that the Shepherd Lord was fond of gazing at the stars whilst tending his flocks at night, and this minded me of the portentous star over Bethlehem.

Great story, I thought – someone must have written a novel about it – but try as I might I could not find any mainstream literature on The Shepherd Lord, only a poem from Wordsworth, “The Feast at Brougham Castle”, and an obscure and anonymous old poem called “The Nut Brown Maid” which alluded to the story. When I bought my copy of The Nut Brown Maid from an antiquarian bookshop, I learnt that this poem would have been lost to posterity had it not been found in a bundle of old papers. It was then printed and promoted by none other than Samuel Pepys and I thought that it would be a great shame if the Shepherd Lord story was lost or forgotten. With the Nut Brown Maid we also had an added love interest to the main arc of the story, as this alludes to the Shepherd Lord marrying Henry VII’s cousin, Anne St. John, and from that moment on I could not rest until I had laid the plot down on paper. I used to wake up in the middle of the night to write half a chapter or so before wearily trudging off to work next morning. But, before long, the story was complete.

The Shepherd Lord is a work of fiction, but it’s clearly based on a great deal of research. How did you go about researching the story? Were there any sources that you found particularly helpful?

Well, the family history book was a good source of information , as were the museum staff at Bolling Hall. The mainstay of information was Richard T. Spence’s book The Shepherd Lord of Skipton Castle but, to be honest, not much is recorded about Henry Clifford’s life from 1461-1485, when he was in hiding, so I had to cast my net quite wide. That’s when I found that people were only too pleased to help out with my research. Adrian Waite, who is an expert on the Clifford family, helped me discern the fact from the fiction and Sebastian Fattorini, who now owns Skipton Castle, the ancient seat of the Clifford family, was an enthusiastic supporter. The Richard III Society pointed me to some good references including a rare book by Jean Gidman on the Stanley family, who occupied Skipton Castle whilst young Henry was in hiding, and the Towton Battlefield Society had lots of really good books on the period.

As for the rest of it, I had to make it up. In the best Hollywood tradition, I bent some of the historical dates to fit the arc of the story and introduced some fictional characters. The characters are fictional in the sense that there is no official record of them, but people like them must have existed for the story to happen. For instance, it is known that the Shepherd Lord had a natural born son called Anthony – for Anthony to exist he had to have a mother so I invented the character Lénaïg. If the Shepherd Lord was being pursued, who was his pursuer? So I came up with the odious assassin character, Eldroth. When I had all the characters assembled, both historical and fictional, it was really easy to write the story around them.

One of the strengths of the book, for me, is its sense of place: you paint an evocative portrait of the North of England, both in terms of its landscape and its people. Speaking as a writer, was this something you consciously set out to achieve, or did this come naturally?

I suppose that the answer to this question is both. I have a strong passion for my native North Country, a great respect for its proud, independent and often taciturn people, and a lasting love affair with the scenery of the rolling hills of the Yorkshire Dales and the majestic peaks of The Lake District. So, this part is deeply rooted in the sub-conscious.

Consciously however, I wanted to give it a real Northern flavour. Robin Hood was a Yorkshireman but to this day, people think he plied his trade in Nottingham. I did not want some latter day Brian Clough twisting this story so I set out to give it a real gritty Northern stamp.

What intrigued me was how this young boy, born to one of the greatest peers in the realm, would cope with being brought up by rough country people. This is where the use of dialect came in to contrast an elegant thoroughbred living with that of the everyman. I hope it gives the book a real sense of character, place and purpose.

I also wanted to make this book a bit of an anthem for Yorkshire. Going back to William the Conqueror’s reign, with the Harrying of the North, and before that the Danelaw, this region has always fought, and suffered, to maintain its identity. Telling the story through the eyes and with the tongue of a gruff, but kindly, Yorkshire shepherd was a departure from the clichéd tales of knightly derring-do.

I understand that you’ve recently given some talks in schools. How have young people responded to the story of the Shepherd Lord?

Young people are really uplifting. Our society is sometimes unfairly critical of them but I find the experience of talking to them is inspirational.

I normally start a talk with a show of hands for who likes reading books. Most of the class will raise their hand skywards but there are one or two who guiltily keep their hands down with a furtive glance in their teacher’s direction. I then ask who likes going to the movies which is always greeted with thrusting hands and beaming faces. I then explain that I made a movie-style trailer to promote the book on the Internet :

http://www.theshepherdlord.com/index.html

and that writing a screenplay is a very different proposition to writing a novel. At that stage, I have the attention of the majority of the class and we get into all sorts of discussion on writing styles and the creative process.

Taking a few props from The Shepherd Lord trailer, like the crook and the sheepskin jerkin, also helps and prompts discussion.

Judging by the questions they ask me and the smiles on their faces they respond well to this little story. I guess they can relate to the central character as they are of a similar age, and they like the idea of the hostile pursuit and epic journey.

From my perspective, I am pleased they take such an interest and am always happy to spot one or two very knowledgeable little history buffs.

Could you tell us a little about your future plans?

Well as far as the book is concerned it has been entered for the Portico Prize this year. It is up against such luminaries as Joan Bakewell and Joanna Trollope, so I guess it faces some really tough competition. On my part, I am just honoured to be even considered in such esteemed company and I already feel gratified that I have managed to give this wonderful old tale another airing.

With regard to my future plans, I have written the sequel, Dead Man’s Hill, and the Publishers are scheduled to release it in 2012. This plots the remainder of the Shepherd Lord’s life, from his tranquil existence in pastoral rural Yorkshire to his call to arms to take a command at the Battle of Flodden – to prove the instinctive martial skills of John Clifford’s son and heir.

Currently, I am concentrating on my search for the elusive and enigmatic Towton Rose, with the help of the famous rose expert Peter Boyd. This legendary white rose is speckled with red to represent the blood of the fallen at Towton and is said only to grow on spots where the blood of the dead soldiers has fertilised the ground. As you would expect, I am compiling the romantic mystery behind the rose and Peter is bringing some much needed pragmatism and science to the subject.

Thank you, George, for agreeing to take part in this interview. We wish you success in your quest for the Towton Rose!

Part of the proceeds will be donated to the Towton Battlefield Society.

ENDS