Richard Neville – the legend and legacy of ‘Kingmaker’

In the summer of 2010 Nick Clegg, leader of the Liberal Democrats, found himself in a wholly unfamiliar, vaunted position. The outcome of the 2010 election still unknown, it was said that both of the opposing parties, Labour and Conservative, without the seats to gain an overall majority in Parliament, jostled for his valuable support in forming a government. The Liberal Democrats were thrust forward onto the national stage. In this context, the Press developed a famous moniker which would help define Clegg’s position; that of the ‘Kingmaker’. Clegg in such a role was seen as ready to crown either Gordon Brown, the incumbent Prime Minister, or David Cameron, his Tory opposite number, as newly elected leader of the country. Although this role may have been exaggerated, it seemed that Clegg did indeed hold the power to crown one man or the other through his influence and new found political authority. Clegg himself was eager to distance himself from the term, issuing a disclaimer stating: ‘I am not the kingmaker. The 45 million voters of Britain are the kingmakers. You are the kingmakers. You give the politicians their marching orders, not the other way round. It’s called democracy, and I kind of like it’.

Regardless of this however, the term stuck. And it is a term with a strong tradition in European history, an expression used and applied generally to a person or group that has great influence in a royal or political succession, without necessarily being a viable candidate. In a Roman context, Flavius Ricimer (c. 405 – August 18, 472) as magister militum of the Western Empire, exercised political control through a series of puppet emperors. However perhaps more famously is the example of Richard Neville, 16th earl of Warwick, during the period known to history as the ‘Wars of the Roses’. The Wars raged sporadically in three phases; between 1455-61, 1469-71 and 1483-85. Between 1455-61, Warwick fought in a multitude of battles on the side of the Duke of York; at both battles of St Albans, at Ludford Bridge, Northampton, Ferrybridge and Towton.

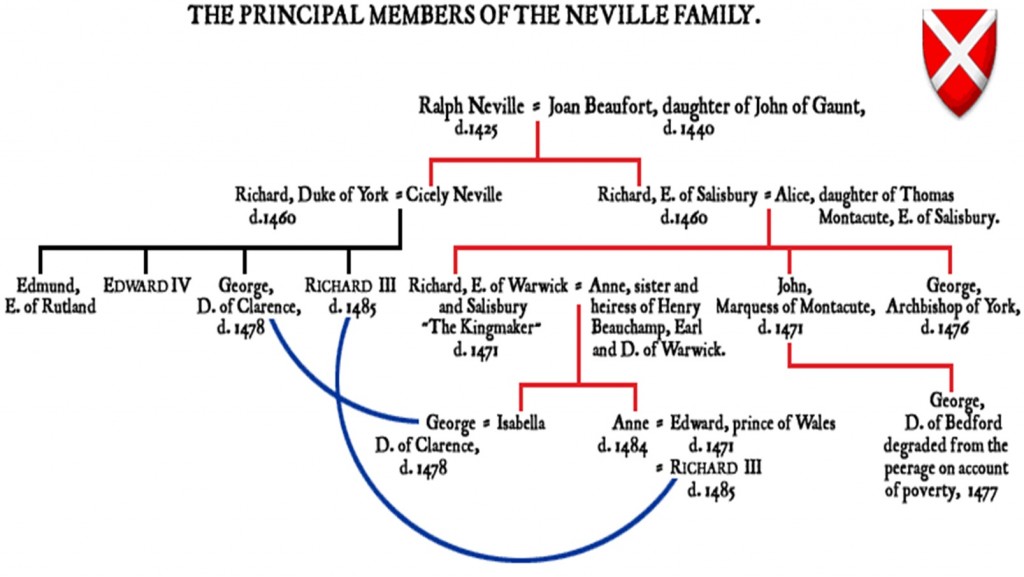

Richard Neville was born on 22nd November 1428, the eldest son of Sir Richard Neville and his wife, Alice Montagu, who were recognised as Earl and Countess of Salisbury in Alice’s right on 7 May 1429. As Hicks states; ‘From the very moment of his birth there was mapped out for him a political and military career as the head of one of the dozen leading English families’. The Neville’s were one of the greatest and fastest growing families of northern England. Firstly, their position and lands in the north (primarily in Durham and Yorkshire) were incredibly useful to both Richard II and Henry IV in order to counterbalance the strength of the Percy’s on the Scottish Borders – hence Richard’s grandfather was made earl of Westmorland in 1397, and appointed as Warden of the West March in 1403.

Family Tree of the Nevilles, showing the links with York (Source: David Harpham)

Warwick’s emblem of the Bear and Ragged Staff

In being born in such lofty circumstance and into a family of such influence, Richard was born into great privilege. However, aside from his marriage, little is known of Richard Neville’s early life. We do know that by 1445 Richard had been knighted, probably at Margaret of Anjou’s coronation on 22 April that year. He is visible in the historical record of service of King Henry VI in 1449, when mention is made of his services in a grant and performed military service in the north with his father, possibly taking part in the war against Scotland in 1448–9. However, the most significant fact surrounding Neville’s early career surrounds his inheritance; when in 1446 Richard de Beauchamp’s son Henry, who was married to Richard’s sister Cecily, died and was followed by Henry’s daughter Anne in 1449, Richard found himself jure uxoris Earl of Warwick. This title and in particular the land it held, comfortably made Neville, at the tender age of 21, one of the richest noblemen in England.

The newly made earl of Warwick came of age and into politics at a time of escalating political crisis. Military defeat had led to the collapse of English power in France during the 1440s. Moreover, the weakness of Henry VI had meant that his Council was increasingly seen as being dominated by men such as the Duke of Suffolk, men who held little influence but governed alone in the King’s name, refusing to co-operate with what Hicks terms ‘the ancient royal blood of the realm’. Although Suffolk’s services were relinquished in 1450, King Henry governed on through his almost equally discredited colleagues, withstanding the growing tide and appetite for reform, seen most clearly through the rebellion of Jack Cade in June/July 1450. Cade and his followers criticised the King’s ‘false council’ and called in their ‘proclamation of grievances’ for the removal of ‘all the false progeny and affinity of the Duke of Suffolk and the taking about his noble person his true blood of his royal realm’. In this regard they were referring to Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York who, seeing both a chance to reform royal government and to regain what he considered his rightful place at the centre of such government, returned from his Lieutenancy of Ireland, arriving in London in September. Once in the capital, York promoted a public stance of a reformer, demanding better government and the prosecution of the traitors who had lost northern France.

However these were not demands which were reiterated by the Neville family, despite their links to the Duke through marriage. Between 1450-52, the Neville’s attempted to mediate reconciliation rather than encourage conflict. At Dartford on 1st-2nd 1452, when the Duke of York unsuccessfully rose up against the king, both Warwick and Salisbury were among the six ambassadors who negotiated the armistice, an indication of their acceptability to both duke and king. However within a year, this stance of apparent neutrality and mediation had been transformed and the Nevilles, Warwick included, threw their lot in behind York in defiance of central royal government. So what brought around this change in attitude? Firstly, it is important that we should not take the seemingly happy concord and apparent unity of nobles against York at face value. Hicks recognises that ‘many issues, public and private, divided the peerage in 1450-53, even when apparently most united against York’s Dartford coup, but they had not caused any firm taking of sides’. However in 1453 the Neville’s growing local rivalries with the Percy’s in the north exploded into violent feud. Such violence stemmed both from a sequence of position enhancing appointments and claimed inheritances, combined with an increasing inability for both families to provide for their younger sons. Warwick, in his close ties to his father and family, was intrinsically linked into this conflict. Additionally, he was also a great lord and landowner in his own right, with an increasing independence of interests from his father. One such interest lay in Glamorgan, south Wales, where, since 1450 the Duke of Somerset and Warwick had squabbled over the Despenser inheritance. However by June 1453 and backed by the authority of the crown, Somerset, who had taken Suffolk’s place at court as one of the King’s favourites, was ready to make his title good. In force, and anticipating resistance, Somerset’s men entered the lordship and were resisted.

Then, in the summer of 1453, King Henry fell suddenly ill. Both these disputes and the King’s illness transformed both the Nevilles and Warwick’s relationship with government. With the King incapacitated, Somerset, Warwick’s challenger in Wales, was virtually in complete control of government. From this point, Hicks states that ‘the full authority of the crown was deployed in favour of Somerset and the Percies and against the Nevilles’. As Hicks states; ‘Actions against their interests by the court placed them logically in the opposition and the madness of the king made York into an avenue through which to achieve their aims, attempting to reform the government and hence ensure their own position in it’. Separate feuds were now becoming entangled and the two sides were emerging. Two years later in 1455 it is striking how rigid remained some of the allegiances contracted in the private violence and confusion of 1453-55. At the first battle of St Albans in May 1455 Northumberland and Somerset were in the king’s entourage; Salisbury, Warwick and the rest of his family stood with York. It can be no surprise that during the battle, when Warwick made the crucial contribution in leading the charge through the town’s defences, both Northumberland and Somerset, Neville and York’s main enemies at court, were amongst the limited number of dead. Neville victory and revenge seemed complete.

The period 1453-59 would see Warwick increasingly become a political figure of the front rank, overtaking his father in both power and influence. When York was appointed Protector of the realm in February 1454, Warwick was admitted to the Council. Later, during York’s second protectorate the earl was further promoted, rising to the position of Captain of Calais. In such a position, Warwick spent much of the next four years fighting the French and Spanish in the Channel, winning a great reputation as a naval commander. When the second protectorate was ended by Henry’s recovery in February 1456, this appointment was one of the few acts of York’s which was allowed to stand. But Warwick’s lofty position was not just seen through his martial achievements; he fully took his place at the top table of English nobles. In 1455 after St Albans, in a symbolic gesture tinged with political significance, it had been York, Salisbury and Warwick who led the captured King back into London after the battle. Additionally the great ‘Loveday’ procession of 1458 further showed how Warwick had entered the pantheon of higher English nobles. In this procession, in a gesture of reconciliation and stability, the King in his crown and robes of state marched from Bishops Palace to St Pauls Cathedral. Warwick took a prominent position in front, marching alongside his former enemies and his father; Somerset, Exeter and Salisbury, with York and Queen Margaret to follow. However this day of reconciliation simply masked over and obscured a number of simmering tensions. For example, privately the Duke of Exeter was furious at being replaced as lord high admiral by Warwick. Seward illustrates the anger behind such a move in recognising that when the earl attended a council meeting at Westminster in November 1458, fighting broke out between his men and the King’s servants, who then attacked him. The renewal of civil war would predictably follow in 1459 and Warwick, as Captain of Calais, was to play a key role. York personally summoned Warwick and part of the Calais garrison to England, but after the Yorkist defeat at the battle of Ludford Bridge in October, the earl returned to Calais. Henry Beaufort, the new Duke of Somerset, was subsequently appointed to replace Warwick as Captain of Calais, but the earl managed to hold on to the garrison. Here then was the true significance of Calais; it acted both as a stronghold off the English mainland to act as a base of retreat but also gave Warwick a loyal resource of manpower, swayed by his reputation and the fruits of their Channel piracy.

After spending the next eight months gathering strength and raiding the English coast from the Calais garrison, the Yorkist earls re-entered London in June 1460. The following month Warwick himself defeated and captured the king at the battle of Northampton. It is impossible not to underestimate the significance of this. With royal government and the king’s person now in Warwick’s hands, York returned from Ireland in September. It was at the parliament of October that year that York first made formal claim to the throne. Abbot Whethemstede of St Albans describes the moment at parliament in Westminster; ‘York came to the king’s throne, upon the covering or cushion of laying his hand, in this very act like a man about to take possession of his right…’. Such a symbolic act of laying his hand upon the throne left the assembly in shock. It is unclear whether Warwick had prior knowledge of York’s plans, but Waurin, the Burgundian chronicler, claimed that the reaction of York’s friends were extremely hostile for he had acted ‘completely in isolation’. Waurin talks of a confrontation between Warwick and York surrounding this claim; ‘…and there were angry words for the earl showed the duke how the lords and the people were ill content against him because he wished to strip the king of his crown’. However, whether he agreed with this move or not, Warwick’s vital contribution at Northampton had clearly allowed York to feel confident enough to claim the throne; perhaps Warwick was here first the inadvertent and accidental ‘Kingmaker’. However it was clear that this regime change was unacceptable to the lords in parliament and a compromise was agreed. The Act of Accord of 31 October 1460 stated that while Henry VI was allowed to stay on the throne for the remainder of his life, his son Edward, Prince of Wales, was to be disinherited. Instead, York would succeed the king, and act as protector. However, as was to be expected, the plan was immediately rejected by the queen, Margaret of Anjou, and her supporters. Further conflict was inevitable. With Lancastrian supporters such as the Earl of Northumberland, Lord Clifford and the Duke of Somerset, all sons of York’s political rivals who had been killed at St Albans, rallying in the north, York and Salisbury marched out of London in early December. Such action had deadly consequences; after an inconclusive skirmish at Worksop in Nottinghamshire, in 30 December 1460 York was killed at the battle of Wakefield. Salisbury was executed a day later.

The earl of Warwick, left in charge of the capital whilst his father marched north, was now the unchallenged heir of his father and head of the Neville family. However his first act in response to the death of his father was not a successful one. Marching north to confront the enemy, he was defeated and forced to flee at the Second Battle of St Albans. Not to be bowed, he joined forces with Edward, earl of March, the eldest son and heir of York, who, in contrast, had won an important victory at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross two weeks earlier. While Queen Margaret was hesitating to make her next move, Warwick and Edward hastened to London, where Edward was quick to claim the throne. However, in noticeable contrast to his father’s claims, Fabyan’s chronicle makes it clear that the people of London were only too happy to accept Edward of March as their king. Trevor Royle states that ‘Fear of the Lancastrians was one reason, a general despair after the years of misrule was another, but the main reason was that March offered the means of changing a system of governance which had fallen into disrepute and many now wanted changed’. On 4 March the prince was proclaimed King Edward IV. The new king now headed north with Warwick in order to consolidate his title, and met with the Lancastrian forces at Towton in Yorkshire. Warwick had suffered an injury to the leg the day before in the Battle of Ferrybridge, and may have played only a minor part in the battle that followed. Despite this, the unusually bloody skirmish resulted in a complete victory for the Yorkist forces, and the death of many important men on the opposing side, such as Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, and Andrew Trollope. Queen Margaret managed to escape to Scotland, with Henry and Prince Edward. Edward returned to London for his coronation, while Warwick remained to pacify the north.

As Santiuste recognises; ‘Warwick has traditionally received the credit for Edward’s accession to the throne’. Certainly, contemporary foreign observers believed that Warwick was fully in control of events. In 1461 the Milanese Prospero di Camulio had reported that ‘My lord of Warwick has made a new King of the Duke of York’s son’. The Governor of Abbeville joked in a letter to the French king Louis XI, ‘They have but two rulers, M de Warwick and another whose name I have forgotten’. This may be over-exaggerating Warwick’s clutch on power and imagined control over Edward, although Edward did frequently look to Warwick’s guidance. Closer to the mark may be the Scots Bishop of St Andrews description of Warwick as; the ‘governor of the realm of England beneath Edward IV’. In recognition of this, Warwick’s position after the accession of Edward IV was stronger than ever. There is no doubt that he was the Crown’s richest subject, owning more than a hundred manors in twenty-one counties. He had also now succeeded to his father’s possessions, and in 1462 also inherited his mother’s lands and the Salisbury title. Altogether he had an annual income from his lands of over £7,000, far more than any other man in the realm but the king. Moreover, Edward had most lavishly rewarded Warwick and his family for the invaluable services they rendered to the Yorkist dynasty during the takeover of power in 1460-61 and the subsequent fighting in the North. In particular, Warwick received large parts of the earl of Northumberland’s holdings, and was made ‘the king’s lieutenant in the North and admiral of England’.

By the year 1464 the political scene was also looking undeniably good for both Edward IV and the earl of Warwick. Warwick had comprehensively defeated the northern Lancastrian rebels, sending Margaret of Anjou into exile, leaving Edward as the undisputed ruler of England. Henry VI was captured in July 1465 and imprisoned in the Tower of London, completing the picture of Yorkist domination. Indeed, as Ross argues, the Lancastrian cause was now so crushed and discredited that it had no hope of revival unless the victorious Yorkists quarrelled amongst themselves and one faction sought refuge under the banner of the House of Lancaster. The parties involved were soon to oblige. The first and most significant tensions surrounding the two individuals consist of that over both foreign and domestic policy. During the 1460s the earl pursued from Calais a pro-French foreign policy at increasing odds with the pro-Burgundian one sponsored by Edward IV. At the heart of this was the issue of marriage. At twenty three Edward IV was the most eligible bachelor in Europe, a man in Commynes opinion; ‘so vigorous and handsome that he might have been made for the pleasures of the flesh’. By the early part of 1467 both Burgundy and France were eager for an English marriage alliance. Warwick, believing that he could continue to rule through Edward, pressed him to enter into a marital alliance with a major European power, his preference being a princess of France.

However in 1467, during a Great Council held on St Michaelmas day (28 September) at Reading Abbey, Edward made a startling admission; three years earlier he had married in secret. This was not a marriage to a princess in Europe or to woman of like rank in society but to the widow of Sir John Grey, a Lancastrian sympathiser, a lady named Elizabeth Woodville. The announcement at Reading Abbey humiliated the Earl of Warwick. Only recently he had been in France negotiating in good faith a marriage between Edward and King Louis XI’s sister-in-law. Moreover, as Kekewich recognises, the members of Elizabeth Woodville’s large and impecunious family quickly became figures of hatred for the populace and occasions of discontent amongst the political elite. What specifically angered Warwick was the need for Edward to provide for the Woodvilles – the new queen’s family were quickly allied through marriage with many of the greatest English families as well as with some new men, such as Sir William Herbert. This Herbert-Woodville marriage particularly hurt Warwick as Herbert was the King’s man in Wales, an area Warwick coveted. But more importantly, the scooping of the baronial marriage market for the benefit of the queen’s relatives specifically deprived him of suitable husbands for his own daughters, the greatest heiresses in England. For example, the correspondence of an anonymous chronicler, formerly attributed to William Worcester states; ‘the king caused Henry, duke of Buckingham, to marry a sister of Queen Elizabeth to the great displeasure of the earl of Warwick’. Only Gloucester and Clarence remained, the King’s own brothers, and Edward stubbornly refused such alliances. Thus Warwick was left with two daughters with large inheritances, without like families to marry into. The marriage of Edward had not only hurt Warwick’s reputation abroad, but now the Woodvilles’ marriages into the nobility were hurting future prospects for his family.

Warwick certainly felt that he was being edged out, as he saw it, by the Woodvilles, who stepped into the role of ‘evil counsellors’. At first, although the rise of the new queen’s family alienated him, Warwick dissembled his anger. However then, despite Warwick’s vehement opposition, Edward pressed home his plans for a Burgundian alliance and in July the Duke of Burgundy and Margaret of York were married in ceremonies of the greatest splendour. The anonymous Croyland Continuator, thought to be connected to one of Edward’s councillors, called this event the ‘real cause of dissensions between the earl and the king and not the marriage between the king and Queen Elizabeth’. Warwick’s hatred for a Burgundian alliance is stated by the Croyland Chronicle; ‘It being much against Warwick’s wish that the views of Charles, now duke of Burgundy, should be in any way promoted by means of an alliance with England. The fact is that he pursued that man with a most deadly hatred’. At home, rumours spread of further discord between the two men as Worcester records; ‘secret displeasure continued between the lord king and the lord earl of Warwick about the marriage between the Duke of Clarence and the said earl’s daughter which marriage the king ever suspected them of making in secret’. On 11 July 1469 Clarence did indeed marry Warwick’s daughter Isobel Neville in Calais, in defiance of the explicit orders of Edward. Soon after, Warwick made his move. In July Warwick released a manifesto with familiar griavances listed, such as ‘lack of governance’. He further stated that his aim was to ‘save his Grace from the deceivable and covetous rule and guidance of certain seditious persons’. From Calais both Clarence and Warwick crossed to Kent in order to raise rebellion.

So what ultimately led to Warwick taking such an extreme step? Perhaps Warwick believed that he deserved more credit and reward for Edward’s accession. Perhaps he felt that he had lost the King’s confidence and that the King had humiliated him on perhaps more than one occasion. Perhaps he could feel the cold breath of the Woodville’s influence on the back of his neck. All these reasons played a part in events to come. The earl was not the sort of man to take what he considered such obvious dishonour lying down; he had fought to protect his position in 1453 in alliance with York and now, as his own man, would do so again.

Circumstances in England had certainly given Warwick encouragement. We can see in Warwick’s first rebellion evidence that the King’s reign had not totally captured the heart of his people. Towards the end of the 1460’s, many people were starting to feel like Edward’s reign had not been the success everyone had expected. The Woodvilles in particular were unpopular for their supposed influence on the King. Taxation had been too heavy, with too little to show for it. The countryside still swarmed with robbers. Popular feeling was on Warwick’s side. Several local revolts had already emerged, one in response to a tax on corn to subsidize an almshouse in York (Robin of Holderness’ Revolt), but Robin of Redesdale’s invasion, perhaps employed by Warwick, was crucial in capturing popular support. In June 1469, Redesdale had appeared in Lancashire with several thousand men, issuing a clear anti-Woodville manifesto. Statements included; ‘The lord Rivers, Sir William Herbert, Humphrey Stafford etc have so advised the King and caused him to be so affectionate to them that by their insatiable covetousness they have asked, obtained and caused him to be so affectionate to them above their deserts and decree, so that he may not maintain his estates and ordinary charges within his land’. Warwick, Clarence and Neville arrived in Kent unmolested, the rebels being well received due to Warwick’s popularity at keeping the channel free of pirates. Heading north, Warwick joined with Redesdale’s men and soon after destroyed William Herbert’s army at Edgecote, with the King captured soon after. Edward was imprisoned in Warwick, and in August taken north to Middleham Castle. Ross holds that the blame for the humiliating defeat of July 1469 lay firmly at Edward’s door, with ‘a mixture of complacency and inactivity characterizing his behaviour’. Whether this is true or not, the King had certainly underestimated Warwick’s anger at events since 1465 and resolve to restore his influence.

Seward holds that ‘the sequence of events and the changes of fortune which followed between the months from August 1469 and August 1470, when Edward IV again lost his throne, are amongst the most complex and confusing in all English history’. First Warwick attempted to rule by the hopelessly unrealistic expedient of putting Edward IV under strict control and ruling through him; however, it quickly emerged that Warwick would soon find it impossible to rule without Edward’s cooperation. Maybe it is an indication of Warwick’s over-confidence and arrogance that he believed he could do so. The country had wanted the Woodvilles removed from effective power, not Edward. Warwick soon released the King in September 1469. Fleeing to France in 1470 the face of Edward’s denunciation of himself as a traitor, Warwick soon fought back and in doing so, awoke the Lancastrian cause. What happened next is a prime example of the sheer adaptability of allegiance in line with the protection of an individual’s own interests which so characterised the wars. In France Warwick not only enlisted the help of the French government but also that of the exiled Margaret of Anjou, queen of Henry VI. Forcing Warwick to kneel before her and swear his allegiance, Margaret of Anjou agreed to the unlikely alliance, which had the express aim of the restoration of the still imprisoned Henry VI to his throne. Here, not for the first time, European politics also played a decisive part in the Wars of the Roses; Louis XI of France was also convinced by Warwick’s intentions and saw his chance for an anti-Burgundian alliance. Gillingham states that ‘as soon as he knew of Warwick’s landing, Louis knew it was time for restoration of Henry VI followed by an Anglo-French military alliance against Burgundy’.

Back in England, Edward IV began to make hasty preparations against such an alliance. An Anglo-Burgundian blockade patrolled the channel, and it was only when Edward’s fleet was destroyed by a storm that Warwick could land unmolested. With the King unwisely staying in the North putting down a rebellion, the people of the South decided to shed their loyalty and did not offer resistance. With the support of Stanley, Shrewsbury, Clarence, Jasper Tudor and Oxford, as well as the previously loyal Montagu’s large army betraying Edward, the King swiftly fled in the face of such numbers. Henry VI was released from captivity and took up the throne without worry. In the last months of 1470, with Edward IV in exile and Henry VI restored, principally due to the ‘Kingmaker’s’ actions, Warwick stood at what should have been the pinnacle of his power. It must have seemed like a great triumph, although in truth Warwick was in a difficult position. In reality he needed to reach out to former supporters of Edward’s regime, but this was a difficult balancing act; as yet there was very little with which to reward loyal Lancastrians who would have expected some reward for their service. In addition, as Santiuste recognises, with the return of Henry VI and his Queen, the Duke of Clarence must have felt especially vulnerable. Gone were his claims to the throne; even the lands and titles he had received from his brother were under threat. Yet, at this point, international affairs again intervened.

Illustration of the Battle of Barnet on the Ghent manuscript, a late 15th-century document (Source: Wikipedia.org)

Edward was quick to seize upon the opportunity the death of his ally turned enemy had presented him. First he turned his attention to the remaining Lancastrians, eliminating the remaining resistance at the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471, where Prince Edward, the teenage son of Henry VI was slain. Two weeks later Edward would pass sentence of death on Henry VI in the Tower. The Lancastrian direct line had been crushed. Then, recognising the importance of removing Warwick’s legacy, Warwick’s offices were divided up. Here King Edward’s brothers Clarence, and Richard, Duke of Gloucester, were the main beneficiaries. Clarence received the office of chamberlain of England and the lieutenancy of Ireland, while Gloucester was made Admiral of England and Warden of the West March. Clarence also received the earldoms of Warwick and Salisbury. In an attempt to secure the north against any further lingering Neville uprising, Edward IV allowed Gloucester, to marry Warwick’s daughter Anne in 1472. This transferred most of Warwick’s northern estates and influence to the House of York.

By 1472 then the Neville inheritance had largely been destroyed but the legend of ‘Kingmaker’ had been born. I have spent considerable time in this article exploring his life, from his childhood to his death, in an attempt to get behind the myth of the man, but what sort of man was Richard Neville, earl of Warwick? Warwick’s reputation and historical legacy has certainly been a matter of much dispute. Historical opinion has alternated between seeing him as self-centred and rash, and regarding him as a victim of the whims of an ungrateful king. The 1559 work The Mirror for Magistrates certainly portrayed Warwick as a great man: beloved by the people, and betrayed by the man he helped raise to the throne. A section of this work shows Warwick stating that; ‘The common weale was still my chiefest care, to private gain or glory I was not bent’. It went on; ‘I think the earl of Warwick although he were a glorious man, hath said no more of himself than what is true’. In this respect it is certainly been agreed that in his own time he enjoyed great popularity in all layers of society, and that he was skilled at appealing to popular sentiments for political support. The contemporary evidence makes it clear that Warwick was an attractive personality with an affability and openness of character which captivated those who knew him. The contemporaneous Great Chronicle of London states; ‘The which earl was ever had in great favour of the commons in this land, by reason of exceeding household which he daily kept in all countries wherever he sojourned or lay’. His first biographer stated that he deserved the surname ‘Great’ ‘by reason of his hospitality, riches, possessions, popular love, comeliness of gesture, gracefulness of person, industrious valour, and all the signatures of a royal mind and generous spirit’. It was such qualities that meant that in 1469 at the time of his first rebellion, the earl’s popularity exceeded that of the king, although such popularity was perhaps influenced by his work in the channel as Constable of Calais.

However eighteenth and nineteenth century historians instead built upon the perception founded in Shakespeare’s Henry VI trilogy of a man driven by pride and egotism, who created and deposed kings at will. Whig Historians such as David Hume, eager to decry anyone who impeded the development towards a centralised, constitutional monarchy, saw Warwick as an ‘overmighty baron’, weakening the influence and potential for any regular system of civil government. Pride of lineage was transmuted into haughty arrogance and liberality into extravagance. Such a trend continued into the twentieth century; scarcely anyone in the past ninety years has favoured Warwick. For Kendall, ‘Warwick was a gigantic failure…because he poisoned his character and sold what he was for what he ought to be’. Kendall refers here to the deposition of Edward which identified his character with egotism and selfishness. Such historians argued that Warwick arrogantly believed his crucial role in placing Edward on the throne made him indispensible; moreover it meant that his and his families’ position at the centre of government, coveted for so many years, was to be taken for granted. When this was proved not so, Warwick betrayed Edward, arrogantly rebelling against the King and selfishly taking the necessary steps to protect his and his families’ position. The term ‘Kingmaker’ in this context was characterised then more by a sense of your own importance and arrogance than by a commitment to the ‘common good’.

There may be at least some truth in this opinion. There is no doubt that, as illustrated by the events of his life, the characteristics of selfishness and self-interest played a part in the makeup of his character, particularly in Warwick’s attempts to rule through both Edward IV and Henry VI. These attempts showed a certain element of self-interest as Warwick tried to use both Kings as puppets to achieve his own aims. It is such actions that have seen Warwick, as Hicks recognises, comically referred to as the ‘wicked baron’ to whom contenders for the crown submitted application forms that specified their preferred means of death’.

However, it has also become increasingly important for historians in the modern age to attempt to judge Warwick in light of the standards of his own age, rather than holding him up to contemporary constitutional ideals. In recognising this, more historians have engaged with the medieval conception of ‘honour’ in exploring such a complicated personality. The important concept of ‘honour’ certainly played a large part in the development of Warwick’s character. For example, the period running up to 1455 gave Warwick personal experience of the importance of the significance of upholding family honour and challenging personal affronts, defending his and his families’ interests and honour. In this context, every house lord was responsible for defending his household against perceived injustice. Both Percy and Neville showed no remorse or mercy as to put up with injustice and renounce vengeance, which would have meant loss of honour.

Such a tradition of private rights, buttressed by the ethos of chivalry, ran headlong against a developing theory of public authority vested in kingship, with the same traditions of honour and private rights equally applied to events of the late 1460s. When Edward IV destroyed Warwick’s carefully laid plans, the perception of Neville as indispensible was too destroyed. However, more importantly Edward challenged the honour of Warwick, who believed that he and his family were being unfairly squeezed out at home and dishonoured abroad. In this context, Maurice Keen has recognised that the insults to his honour that Warwick suffered at the hands of King Edward in the 1460s were certainly significant. Moreover, Pollard recognises that ‘Warwick’s claim to prominence in national affairs was not a product of illusions of grandeur; it was confirmed by the high standing he enjoyed among the princes on the continent’. In Warwick’s mind then, his high standing was both warranted and deserved, confirmed by his respected standing at home and abroad. It is at this point, in the late 1460s, that the relations between Warwick and York’s heir changed irreparably. Edward was considered to have dishonoured the Neville’s deserved prominence, Warwick, rightfully in his opinion, responded.

Politics has certainly changed since the late medieval period but the character and instinct of mankind has not; the themes of self-preservation, ambition, arrogance and a sense of honour still afflict and bless the political character of the ruling class. When in 2010 the term ‘Kingmaker’ was used in reference to Nick Clegg, there was more than a sense in the media that perhaps the first three attributes were more in evidence than the latter. This has traditionally been seen as the way to approach Warwick, the ‘Kingmaker’ and ‘over mighty subject’. However we can see here that to look at the story of Warwick purely as the tale of selfishness and arrogance is to ignore the complexities of the age and the era of English history to which the man was born. Perhaps it is time once again for Richard Neville, ‘the Kingmaker’s’ reassessment to become complete and a full story in its proper context to take centre stage in the story of the Wars of the Roses.

by David Harpham

Pingback: David Harpham – Warwick the ‘Kingmaker’ | King Richard Armitage