KRA-Week 2013-7: Finding Richard III as a Result of Historical Research – Dr. Ashdown-Hill

Links: King Richard Week 2013 & Quiz

! Attention !

Last day of quiz-entries taking part in the drawing!

(Today till midnight [GMT] !)

Quiz prizes are: Two books by

Isolde Martyn “The Devil in Ermine”

♕ ♛ ♕

History’s new potential

in the discoveries of Dr. John Ashdown-Hill

Why a special article about Historian Dr. Ashdown-Hill here, during the KRA week, when we already had interviews and present his research work here on the website?

- Dr. John Ashdown-Hill talks about his research regarding King Richard III

- Started KRA-page about Dr. Ashdown-Hill’s research. (With recommended video presentation of research steps.)

- Information about Dr. John Ashdown-Hill and his publications.

And other articles already covered the topic of ‘airbrushing’ Dr. Ashdown-Hill out of the story of finding King Richard III:

- Richard III: Historian claims he was ‘airbrushed out of king story’ (by Peter Warzynski, Leicester Mercury, 06.08.2013)

- Leicester ‘airbrushed’ historian out of Richard III find (by Paul Jump, Times Higher Education, 01.08.2013)

There was something I needed to figure out and I want to present some of my thoughts and results to you here.

Dr. Ashdown-Hill is an open-minded researcher, who searched for facts, where others readily followed legend – over centuries.

As the dissection of legend in the case of King Richard III was so very important, to even allow the beginning of the search, I cannot readily understand, why the one man, doing all the work mostly singlehandedly, strongly believing in the validity of his finds, does not get the praise he deserves.

It required already great effort together with Philippa Langley, to even raise sufficient doubt with researchers and officials in Leicester, to get their agreement to do a paid contracted search and give all the required permissions for the digging.

(And here a big motive for the specialists was that they could at least find other historically significant material for Leicester, to make it worth their while, which in the end caused their agreement to start digging.)

But why chose exactly this location for the digging, when the supposed location, indicated by a plaque, was so far away from it?

That was the result of a meticulous research of maps and sources about Leicester – done by Dr. John Ashdown-Hill.

He recognized, that some newer maps were inaccurate (the street drawn at the wrong side of the Greyfriars’ church, according to written sources of contemporaries) and the old medieval streets must have been located a bit differently from what reconstructions of historical Leicester so far made believe.

This changed the location and the area of research entirely and was based on the research of Dr. John Ashdown-Hill.

So, why is there no mention of this fact?

You would think, after all this research so essential for finding King Richard III, there should be a hall of fame for Dr. Ashdown-Hill.

Perhaps next year’s opening of the King Richard Museum in Leicester will remedy that fact and will give praise where praise so clearly is deserved.

We at the KRA website already started our small contribution to a ‘hall of fame’ here and hope to be able to contribute to set things straight.

One aspect, which especially fascinates me in the work of Dr. Ashdown-Hill, is his research, remaining unbiased by the ‘mainstream’ line of previous historical research and starting to get to the fact beneath layers of wrong and long traded interpretation.

This is a fact which exceedingly makes me happy about the research of Dr. John Ashdown-Hill and the finding of King Richard III.

It gives me hope for the art of history in its entirety, that with new perspectives and openness, history with its extensive tools and methods is able to discover great things about the past in the future.

History loses its dust cover and the strictures and rules by some self announced dictators and starts to get truly ‘researchable’ again.

So the real questions about King Richard III for me are not

will he be buried in York or Leicester or …,

was he a good or bad king,

was he a saint or murderer,

but that finding him was able to break up traditional perceptions of a story and a new approach was found and the truth behind it was revealed, after over 500 years!

This fact alone makes me absolutely jubilant!

History is no static entity any longer, but a playground opened up for new research. (While ‘playground’ not in the slightest means this is an easy task, but what history always has been, hard work and an enormous accumulation of knowledge of all kind.)

So go and search and keep your mind open for any possible result!!!

I hope to find out much more about the developments and events leading to the archaeological research in Leicester in the new book by Philippa Langley announced for the end of October 2013:

.

And Dr. John Ashdown-Hill publishes his new research about royal marriage traditions and currently works on a new book about Richard III’s third brother, George, Duke of Clarence:

.

Kindle version:

.

Links: King Richard Week 2013 & Quiz

KRA Week 2013-3: History & Law – Author Matthew Lewis

Links: King Richard Week 2013 & Quiz

♕ ♛ ♕

Interview with author Matt Lewis

about

his research & King Richard III

First of all, I need to confess, having such a knowledgeable author and researcher as interview partner let my curiosity run away with me. I hope you will enjoy the wonderful and insightful answers by author Matt Lewis.

Matt Lewis also currently publishes a series of articles in defence of King Richard III on the Royal Central blog

- The Real White Queen? A Defence Of King Richard III (02.08.2013)

- The Defence of Richard III Part 2 – The Foundations of Evil (06.08.2013)

- The Defence of Richard III Part 3 – To Kill A King (11.08.2013)

- The Defence of King Richard III Part 4 – Bosworth, Shakespeare & That Horse (22.08.2013)

and an interview by Karen Kilrow with more background was published there (13.07.2013).

But now to the interview and my curious questions:

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your historical background?

I have been passionate about history since school, where it was my favourite subject. I studied the Wars of the Roses there and it immediately grabbed me. The intricacies of the family ties, the loyalties and the betrayals are like the plot of the most complex tv series you ever watched, only this was real people’s lives being torn apart.

The story of Richard III was also something I was immediately fascinated by. The difference in his reputation before 1483 and after was so diametrically opposed that it just didn’t make sense. I had to learn more! An interest became a passion. I read book after book about the Wars of the Roses and Richard III and the more I read the more convinced I became that something was amiss.

How does your legal background fit into your interest for history?

At university I studied law and even that seemed to complement the study of history. I find that having a law degree complements an interest in history very well. A solicitor I worked for once told me that no one knows all of the law, the trick is knowing how and where to find what you need. This principle applies to history too. No-one knows all of history.

The skills of research are the same. A law degree teaches you how to find facts, examine and understand them from all angles, to view things from the perspective of others and then present your findings. Historical research is identical. When writing fiction, legal training helps further because it teaches you to understand the facts and then make them prove what you need them to prove!

Why is it so difficult to get unbiased research into the life and times of Richard III, even more than 500 years after his death?

It is hard to understand why Richard III doesn’t get the kind of impartial study almost anyone else does. I think it is due in part to history, for purposes other than academic study, liking to box people up neatly as ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’. The Tudors followed Richard and were keen to present a picture of an England ravaged by tyranny from which they saved a grateful people. Obviously he was then maligned by Shakespeare and that image of him stuck. There has always been a core of historians keen to shine the light of fact on his reputation but it has been hard to fight against a presumed, accepted image. Because of this the argument becomes more polarized as some believe him an evil tyrant and others try to paint him as a saint. Somewhere in the middle the real man is lost. He was neither a saint nor a demon and until the argument moves away from such passionate polarization it will always prove hard to judge him dispassionately.

Might this difficulty to get some resemblance of ‘justice’ for a historical figure have something to do with the current royal family descending from those getting into power after the Battle of Bosworth or the perception of a need to legitimize the later religious separation from Rome or have something to do with a modern interpretation of what monarchy and democracy should be or do?

I think that the present royal family have little impact on the study of the history of personality. They would, I suppose, have a vested interest in the institution of monarchy and so would not wish to become embroiled in any kind of discussion of rights and wrongs. To do so opens them up for such criticism in the future. It is for this reason, I suspect, that the royal family is not keen to allow the opening of the urn in Westminster that supposedly contains the remains of the Princes in the Tower and of other royal tombs such as Edward IV’s for DNA comparison. I doubt that it relates to insecurity or rivalry but rather to the sanctity of those graves. There are human beings resting in peace there. If permission were given now, the same could happen in the future to those still alive now and they may well not want that. Whatever the rights and wrongs of Bosworth, Henry VII was anointed king, whether by right of blood or conquest becomes irrelevant. No-one could challenge the legitimacy of the current royal family now on that basis. If we look further back, Edward IV took the throne by force, as did Henry IV. Do we then head back to William the Conqueror?

Will finding the ‘real’ King Richard III now help with the research to also start the search for the ‘real’ person, not the legend?

The discovery of Richard III’s grave is an opportunity that I hope will be exploited to the full by those seeking a re-evaluation of his reputation. I noticed a real surge in sales of my novel when it was announced, so clearly interest has been captured and just needs to be exploited. The White Queen series has drawn attention to the Wars of the Roses period too. Visitors are pouring in to the exhibition at Leicester and I hope that they will be taking away a different perspective on him, if they are not already Ricardians! I was lucky enough to visit the dig site at Greyfriars on one of the open days and it sent a chill down my spine to think that I could be standing so close to the remains of a man I had studied for so long. I was like a crazed fan. I find it amazing that after everything that has happened on that site – the demolition of the monastery, the building of the mayor’s house and gardens, the demolition of that and all of the subsequent Victorian work, not to mention the laying of the car park – that his grave remained intact and unspoiled, missed by every pick axe and digger that had been on the site. His funeral will be another huge event, unlike anything we have seen before. It would be fantastic to make it there and I will be doing my best to attend some part of it.

I hesitated a bit with the following question, not wanting to heat up the brewing battle. But Matt Lewis answered my question about King Richard III’s last resting place with grace and historical knowledge, so I need not have worried:

With all the discussion about the ‘Battle of the Cities’, what is your position regarding the fighting towns York and Leicester?

In terms of where he should be laid to rest, I have no issue giving my preference. From the very outset there has only been one place that I believe he should be buried and that is Westminster Abbey. He was a king of England and deserves no less. Much has been made of Leicester’s right to him and York’s desire for him. Indeed, it has been claimed that he wanted to be buried at York Minster. Whilst he was lord of the north for his brother this may have been his intention but by the time that he died he was King of England. The clearest indication of his final wishes is the fact that he had his wife buried at Westminster. He may well have intended to have their son moved there from Middleham too, but I think Anne’s presence at Westminster tells us all that we need to know about his wishes.

How do you see the legal aspects of the appeal by the relatives of King Richard III, the Plantagenet Alliance?

The legal challenge that has been brought is flawed in so far as those bringing it are not descendants of Richard III, they are descended from his siblings. It is also my understanding that the reburial of remains discovered during an archaeological dig does not require consultation with the relatives where the remains are over 100 years old, as those of King Richard clearly are. Best practice is to have remains interred at the nearest church or cathedral to the location they were discovered too. Leicester University appear to have done all that was required of them and I suspect that their wish to have him buried at Leicester Cathedral will be, in the end, granted.

You wrote a historical novel about Richard III, clearly depicting Richard III as human being, not the caricature not only Shakespeare, but also some historians made and still make him.

What is your reason to do so and where do you see you have to add to all the previous works and novels about Richard III?

I wrote my novel as an indulgence really. It took about 10 years of picking it up and putting it down but I enjoyed writing and researching it. I tried to remain as historically accurate as possible, not least because the true story is far too interesting to have to invent anything! The book looks at the more domestic side of Richard’s life from the Battle of Barnet when he helped his brother Edward IV regain his throne to Bosworth. Most people know about the battles he fought, the seizure of the throne, the Princes in the Tower and the Battle of Bosworth but I wanted to explore him as a more rounded person, at home with his wife, relaxed with his friends, but still dealing with huge issues of national importance. ‘My’ Richard has faults, too. He is far from perfect. His temper is short and his inability to understand those who do not share his views leave him politically naive and exposed. The actions that he takes in the book broadly follow the known history, so if he attracts sympathy for his actions, it is because he deserves it.

Whatever you decide about him by the end, at least it will be based on fact rather than accumulated mythology.

Studying law helps to view things dispassionately, to detach from them and present them objectively. I am an ardent Ricardian, though I don’t necessarily belief he was without fault. I hope that by presenting a man trying his hardest to make his way in a hostile, uncertain world, struggling to protect his family, I could balance out the saint v tyrant argument a little.

To what extent is your work “Loyalty” based on the research by Jack Leslau about the image interpretation and connection between Sir Thomas More and Hans Hobein? (Research presented on the website: www.holbeinartworks.org)

I first read a brief reference to Jack Leslau’s work in A.J. Pollard’s King Richard III and the Princes in the Tower. It fascinated me and I read more. The more I learned the more interesting it became. In the end it provided the frame through which Richard’s story is told, so there is no doubt that it influenced me a great deal. Ricardians will probably know what that means for the story, but it is not well discussed beyond this. The sequel, which is nearing completion, follows both threads of this story to something which I believe is entirely new. At least I have never come across my next theory before! Holbein returns and we also follow the aftermath of Bosworth as those loyal to Richard who survive try to find a place for themselves in a changed world, a world that hunts them.

You wrote two further works about King Richard III and the Wars of the Roses. Both are rather short volumes with highly condensed information, giving an excellent overview of events and happenings.

What was your reason to write those and for which audience are they intended?

I have begun a series of brief factual history books offering my take on the period I love. A Glimpse of King Richard III was born of the new interest in the king and is a very short biography. It is aimed squarely at those interested in the subject because of the recent discoveries and discussions but who do not wish to dive into a weight biography – though I enjoy these immensely, they are not for everyone. I thought those with a casual interest might pick it up and hopefully put it down with a different perspective on King Richard III. A Glimpse of the Wars of the Roses adds depth to the subject but is also brief, beginning with the roots of the conflict and then following the chronology of the politics and the battles. Again, with interest high and The White Queen drawing much attention, I thought some with a more casual interest in the period might find it interesting. There is more to come in the series too. Hopefully people will enjoy my lighter take on the complexities of the period.

Book publications currently available by Matthew Lewis on Amazon.com / Amazon.co.uk

:

* * *

* * *

* * *

Links: King Richard Week 2013 & Quiz

Sources Sunday: Thomas More’s History of King Richard III

See series introduction, here.

***

Today, I’d like to introduce briefly one of the earlier secondary sources about Richard III, a text written by Thomas More called The History of King Richard III. No matter how you feel about Richard, it’s a cracking read, and the late historian Richard Marius called it “the finest thing he ever wrote.” Even Ricardian biographer Paul Murray Kendall called the work an expression of More’s “stunning vitality.” Here are some things to keep in mind when reading this work.

***

This got really long, so I’ll limit myself to these introductory remarks this week and start talking about specific citations next time.

***

The source itself

- More worked on this text between 1513 and 1518 in Latin and English simultaneously, and never finished it. His English narrative stops at the beginning of Buckingham’s rebellion; his Latin narrative, somewhat earlier, at Richard’s coronation.

- Modern textual scholars believe that More composed the Latin and English versions of the text separately, transferring bits and pieces between them, so that neither text by itself is considered fully authoritative.

- No original of More’s text in his own handwriting (any so-called holograph) survives either in Latin or in English.

- The text was not published in More’s lifetime, possibly because he became too busy to finish it; or because he realized that the matters treated in the text involved too many people who were still alive, so that the appearance of the work would create political problems for him.

- No English manuscript sources survive; several Latin manuscript sources survive, but these are reworkings of the original holograph based on copies that themselves have disappeared in the meantime. The most well-known of the surviving Latin manuscripts — all of which differ — are held at Paris in the Bibliothèque nationale (MS fr. 4996 [Ancien fonds]), and at London in the College of Arms (MS Arundel 43) and the British Library (MS Harley 902). Here’s an excellent technical summary of the transmission of the texts with diagrams. Now considered to provide most authoritative Latin version, the Paris manuscript was rediscovered, entirely by accident, only in the twentieth century, by More scholar Daniel Kinney.

- The “critical edition” of the texts — the definitive version scholars consider closest to the original, which should be used by all researchers — is The Complete Works of St. Thomas More, 15 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963-97).

- Most modern versions of the text produced for general readers or students are emended on the basis of the 1557 London edition: William Rastell, ed., The workes of Sir Thomas More Knyght […]. This was not the first English printing of the text, but it has long been considered the most authoritative as it seems to have been typeset from a no-longer-extant holograph. (Rastell was More’s nephew.)

***

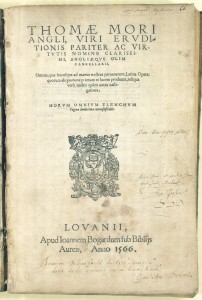

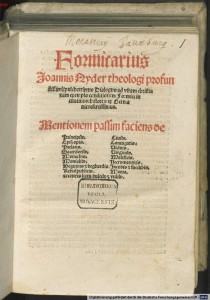

[Right: Titlepage of the 1566 Louvain edition of Thomas More’s works; picture taken from the copy owned by Ben Jonson, the English playwright Ben Jonson. Source.]

[Left: detail of above, with inscription: “Sum Ben: Jonsonij Liber.”; literally, “I am Ben Johnson’s book.” Further inscriptions on the title page reveal that Johnson gave the book to William Dakins, one of the men who translated the King James Bible, whom Jonson probably met at Westminster School. Dakins, in turn, gave it with an inscription to John Blumfeilde.]

[Left: detail of above, with inscription: “Sum Ben: Jonsonij Liber.”; literally, “I am Ben Johnson’s book.” Further inscriptions on the title page reveal that Johnson gave the book to William Dakins, one of the men who translated the King James Bible, whom Jonson probably met at Westminster School. Dakins, in turn, gave it with an inscription to John Blumfeilde.]

***

On More

- More was an extraordinarily talented, intelligent, and complex individual.

- His most prominent intellectual friendship was with Erasmus of Rotterdam, who wrote a hilarious persiflage on the folly of life in general and the abuses of the Catholic Church in particular known as Encomium Moriae, or “In Praise of Folly,” which punned on More’s name (the Greek word for “folly” sounded similar to More’s name).

- Although he became an influential politician and lawyer, and remained a layman, he seriously contemplated a career in the Church.

- In his own age, he was notable for the attention he paid to his daughters’ education.

- The most definitive intellectual influence on More’s writing was that of Renaissance humanism; yet, after he joined the service of King Henry VIII in 1518, he ceased almost completely to write humanist texts and turned to religious polemics.

- Modern readers may know him best for his 1516 work, Utopia (he coined the term).

- More enjoys a reputation as a staunch man of principle, but not always a pleasant one. On the one hand, as Chancellor of England, he vigorously persecuted and prosecuted Protestant heretics. Six were burned on his watch. His polemics against William Tyndale were influential in the latter’s eventual burning for heresy; and George Foxe, who cataloged the sufferings of Protestant martyrs in England, was convinced that More had personally tortured prisoners on trial for heresy. On the other, More has long been respected for his conviction that authority over Church matters should not be ceded to the secular government, as a consequence of which he was executed in 1535 for his refusal to take the 1534 Oath of Supremacy. Was he moral, or a moralist? The twentieth century tended to see him as moral (as in the much celebrated stage and screen drama, The Man for All Seasons), while more recently, in Wolf Hall (2009), for which she won the Booker Prize, Hilary Mantel has portrayed him as a petty, cruel tyrant.

***

[Right: Paul Scofield as Thomas More, insisting to Parliament that he has not committed treason, in the film version of A Man for All Seasons. Scofield won the Oscar for Best Actor in 1966 for this performance and a BAFTA as well. Source.]

[Right: Paul Scofield as Thomas More, insisting to Parliament that he has not committed treason, in the film version of A Man for All Seasons. Scofield won the Oscar for Best Actor in 1966 for this performance and a BAFTA as well. Source.]

***

***

***

General features of More’s history of Richard

- More probably chose Richard as a topic because of his interest in politics and good government. The book is a foil to Utopia (1516), which discusses perfect government and decries amorality in politics; More saw Richard as the epitome of bad, because amoral, government.

- Humanists saw the point of history as teaching life lessons (historia magistra vitae); despite his many dastardly individual features, Richard in More’s eyes was much more a negative example or pattern rather than a fully formed individual. While More clearly believed what he wrote of Richard to be true, the goal was neither a smear job nor the presentation of evidence about Richard’s reign, but rather the crafting of a tale that criticized amorality, hypocrisy, and vaulting ambition.

- According to scholar George M. Logan, the most important influences on More’s structuring of his history are the Greek author Lucian and the Roman historians Sallust (who wrote histories of the Roman traitors Catiline and Jugurtha) and Tacitus (who wrote a history of the Roman emperor, Tiberius). So great is More’s admiration of Tacitus that he alters facts in his portrayal of Edward IV in order to make his reign seem more like that of Augustus.

- We cannot see More as a straightforward Tudor propagandist; he despised Henry VII.

- More’s history counts as a secondary source in that he did not witness the events he describes. He did draw on primary sources: oral information and reminiscences of people he knew who had lived through events. These included his father (the only source he explicitly names), but more importantly gossip in the household of Bishop John Morton, one of Edward IV’s officials implicated in Hastings’ conspiracy, who survived Richard’s reign. More served in Morton’s household he served as a page from 1490-2.

- While as a public official, More could have consulted extant public records in London, textual comparison suggests that he seems to have done so only once (for Buckingham’s speech of June 26, 1483).

- Though it is extremely unlikely that More knew the work of the second Croyland Continuator, which was unknown outside of its abbey until the later sixteenth century, his account squares with it in important details, another reason to discount the charge that More (or Croyland) were mere Tudor propagandists.

- The only written historical works that More can be proven to have consulted are Fabyan’s New Chronicles of England and France (1516/7) and Great Chronicle of London (ms., 1512).

- No textual evidence suggests that the work on Richard most typically cited as Tudor propaganda, Polydore Vergil’s Anglica historia (ms. 1513), was influential on More.

- The conventions of Renaissance humanist historiography required More to concoct all of the speeches; readers at the time would have known this.

- More’s most prominent literary and linguistic device throughout the work is irony; readers must thus be very careful to discern his meaning, since his words are frequently pointed in specific ways.

- Although the text was one of the most popular works of history in later-sixteenth-century England, it had little influence on history-writing. It made its deepest impact, of course, on Shakespeare, which is the main reason a reader might care about it these days.

- Richard Marius makes the interesting assertion that Richard III is one of the first hypocritical protagonists in the history of western literature.

Further reading

Further reading

- Read More’s History of King Richard III on the web, transcribed from the original English edition of 1557 (with original spelling, but modern typography) here.

- If you like books and ready-to-use scholarship, a fantastic update with extensive notes and sixteenth-century usage retained, but modified to reflect modern spelling, has recently been produced: George M. Logan, ed., The History of Richard III: A Reading Edition (Bloomington: Indianapolis University Press, 2005). This is the one my students will be reading.

- Read More’s history in Latin, in the edition that English playwright Ben Jonson used with his notes visible in the margin, at The Center for Thomas More Studies, in digital facsimile.

- Read More’s others works at Center for Thomas More Studies at the University of Dallas as well.

- Richard III Society resources on More’s history, including excerpts from relevant pieces of Marius’ biography, Thomas More: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1984). (Marius’ biography of More is excellent — a much better work than his disappointingly partisan biography of Martin Luther.)

***

If that’s not too much — I’ll be back next week to discuss some of the fascinating points in More’s retelling of Richard’s story.

David Harpham – Warwick the ‘Kingmaker’

Historian & Author

♛ David Harpham ♛

David Harpham

Today, I can present a new contributor and very talented young historian her on the KingRichardArmitage website:

David Harpham

He studied at the University of York and at the University of Sheffield, where the dissertation for his Masters degree in Medieval History focused on the relationship between the Nobility, the ‘Community’ and emerging perceptions of ‘the Realm’ in the Wars of the Roses era. (Short biography available here.)

David Harpham’s articles I read so far, convince me that a bright writing career lies before this young historian.

Earl of Warwick “Kingmaker” (Source: wikimedia.org)

What David can do with a biography about Richard Neville, 16th earl of Warwick, called ‘the Kingmaker’, is really a joy to read and easily bridges the gap of over 500 years to our time.

David Harpham will entrance you in the life of a fascinating major player of the ‘Wars of the Roses’, who was so very influential for the education of the young Richard III during his time at Middleham.

Warwick the ‘kingmaker’ is also King Richard III’s father-in-law, as Richard III later married his daughter Anne Neville.

But now, I won’t divulge much more here and directly lead you to the full article:

David Harpham – Richard Neville – the legend and legacy of ‘Kingmaker’

“Royal News & Battle Report”

David Harpham here also has an interesting article with the historian’s perspective on the ‘Battle of the Cities‘:

Richard III – Heritage magnet or Tourism treasure?

♛ King Richard III ♛

- The Australian: New battle looms over Leicester tomb for Richard III, by Nico Hines (14.03.2013)

Dr. John Ashdown-Hill (interview with Dr. Ashdown-Hill here on KRA) says about the position of Leicester Cathedral:A king should not be buried under the floor.

Nico Hines, The Times:Even Henry VII, the first Tudor king, felt the man he had defeated at the culmination of the War of the Roses was worthy of a tomb. He had one commissioned and built nine years after vanquishing his opponent, but it stood empty and was eventually lost while the dead king lay in an unmarked grave.

- New Statesman: Richard III’s reburial has reignited a Facebook War of the Roses, by Amy Licence (14.03.2013) – The ‘Battle of the Cities’ reaches the social networks.

- ThisIsLeicestershire.co.uk: Richard III: Leicester mayor rejects York summit over burial of king, by Peter Warzynski (14.03.2013) – Comes at a not very opportune moment, when the discussions already are heated further because of the objections Leicester Cathedral has against the tomb for King Richard III by the Richard III Society.

- ThisIsLeicestershire.co.uk: Richard III: Give king tomb, not slab, says online poll, by Leicester Mercury (14.03.2013)

- BBC History Extra: What does the discovery of Richard III’s remains mean for history? (14.03.2013) – Article about King Richard III and changes for history expected by his discovery in the March issue of the BBC History Magazine.

- Wharfedale Observer: Literary award is dedicated to memory of Peter Algar, by Annette McIntyre (14.03.2013) – The Richard III Foundation honours Peter Algar, who died last year, with The Peter Algar Literary Award.

- ThisIsGloucester.co.uk: Bring Richard III to Gloucester – petition launched, by TheCitizen (15.03.2013) – Now a new competitor in the ‘Battle of the Cities’ with an own petition: http://epetitions.direct.gov.uk/ petitions/46783

City councillor Sebastian Field has launched an online petition to have the remains of King Richard III buried in Gloucester Cathedral.

- Politics.co.uk: Comment: The struggle for Richard III’s body must be laid to rest, by Hugh Bayley, Labour MP for York Central (15.03.2013)

- Yorkshire Post: Compromise deal could see Richard III lie in state at York Minster (16.03.2013) – A compromise for a warrior king.

- ThisIsLeicestershire.co.uk: A tomb is right thing for a king, by Leicester Mercury (15.03.2013)

- Canada.com: Shakespeare the spin doctor, by Arthur Black (15.03.2013) – About the importance of ‘Richards’.

The evil that men do lives after them.

The good is oft interred with their bones.Shakespeare

- ThisIsLeicestershire.co.uk: Richard III: All options still open for king’s last resting place, says Leicester Cathedral, by Peter Warzynski (16.03.2013) – Can’t really say I do understand the remaining ‘openness’ of Leicester Cathedral for a tomb design, when the design brief for the architects clearly states that a tomb design would be rejected. How would you react if you were an architect and wanted your design to be accepted? Can one expect something else than anticipatory obedience?

– RIII-articles from the year 2012 – complete list of the year 2011 –

Interview with Author Isolde Martyn

Interview with

♛ Isolde Martyn ♛

Our interview partner today is well known here on the KRA-website, as Ms Martyn already represented Australia and the research association The Plantagenet Society of Australiy here in this interview.

Today, we want to present Ms Isolde Martyn with her excellent knowledge about King Richard III, his family, background and the time of the Wars of the Roses in general, together with her wonderful book publications.

I am currently reading Ms Martyn’s book “The Devil in Ermine“, which will come out shortly (Yes, I have a pre-verion ;o)

And I can tell you, I can’t recommend it highly enough. I am in total awe of this well researched and gripping depiction of the decisive year 1483 in King Richard III’s life seen and told from the perspective of his cousin, the Duke of Buckingham.

The revolt by Buckingham, the reasons, the background are so well told that I really feel for the characters described in the book and see all the motives so well coming together and building the story. The book really has gripped me.

(I will let you know as soon as the book becomes available. – I know I am cruel here, stoking your curiosity, while I am already reading it ;o)

But now I let Ms Martyn tell you more about her connections and research about King Richard III and her new just published book “Mistress to the Crown” about Jane Shore:

Why do you choose the period of the late Middle Ages? It was a time of hardships, especially for women, of fierce fights and wars man against man, of romantic knights, …

What is so very special about this time period in England that it can especially grip the interest of modern time readers?

The seesawing of fortune during the Wars of the Roses. One moment you have a man who is King of England, next day he is a penniless refugee at the court of Burgundy. Life could change in an instant. This means that a novelist can put a lot of pressure on a historical character. How will he or she react to being charged with treason? Can they regain their lands?

What did especially trigger your interest in the Plantagenets and specifically King Richard III?

I read Josephine Tey’s book, The Daughter of Time when I was 14 and I watched Shakespeare’s history plays.

Apart from Richard III, the person that fascinated me most in that era was the lady spy who passed through Calais. I was determined one day to write a novel about her. To do that well, I needed to go to a university that specialised in the Wars of the Roses and study the Yorkist era properly. Fortunately, I was able to go to the University of Exeter. Yes, and my novel about the woman spy–THE MAIDEN AND THE UNICORN–eventually won major awards in America and Australia.

The research about King Richard III shows that sciences did develop greatly and allow deeper insights, though the time gap between our time and the researched time period becomes greater.

Some things are documented quite well, others are lacking and gaps in our knowledge about the time partially are still great.

How do you cope with those holes in historical documentation for your writing?

You are right, there are few facts. We have to be open-minded about historical sources. For example, how informed were the chroniclers? Where did their ‘facts’ come from? Were they–or their sources–politically biased?

Yes, this lack of information makes it wonderful for the novelist. However, as a historian, I try to adhere to what is known. If Richard was at Middleham on a certain day, I would not have him somewhere else for the sake of the story-plot. I think an author needs to make it clear what is fact and what is fiction in a novel’s History Note and List of Characters. That is why Shakespeare’s wicked Richard III has had such impact. When people see something enacted, they are more likely to accept it as true. There is rarely a note at the beginning of a film saying ‘this screenplay was written for drama and entertainment, and some of it may not be true’.

How do you see the relevance of the current archaeological research about the human remains of King Richard III in Leicester? – For your writing, for the available knowledge about the time, for the interpretation of King Richard III, for Leicester, …

As the skeleton is Richard’s, knowing how tall he was, what he might have looked like or eaten before the battle is marvellous. For historians, comparing the physical evidence with the historical sources and legend raises some interesting issues. For example, the evidence of scoliosis. This means that the Tudor slurs about Richard’s appearance did have an element of truth. The portraits of Richard, where changes have been made to show one shoulder higher than the other, may have to be assessed differently now.

I should like to know from medical experts whether the scoliosis could be due to a heel wound at Barnet or Tewekesbury or from combat practice? Or would he have had the condition when he was a child?

As regards Leicester, if Richard is reinterred in the cathedral, I think Leicester City Council will have to take much greater care of the historical areas of the city, especially those beyond the ring road. These seemed very neglected last time I was there.

What do you do to prepare yourself to get into the mood of the late Middle Ages to write about the time and such realistic characters as you create in your books?

It’s hard to sum this up for you.

I read literature from that era, e.g. Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, and I pick out imagery and phrases that could be used in dialogue.

How would a man have felt at that moment in his life, given the occasion, the weather, what he was wearing, what was at stake for him, who he was dealing with, his health, what he ate for breakfast? It can be the small details that can make a character seem real. When Warwick the Kingmaker knelt so long for forgiveness in front of Margaret d’Anjou in 1470, did his legs go numb (do you say ‘pins and needles’ in German? [Comment CDoart: We say the limbs ‘fall asleep’]) Did he have to be helped to his feet?

What started your interest in the setting and the characters of your new books?

I was going to write a novel about Margaret Beaufort (as a villain) but Buckingham was like a little boy waving his hand in a classroom, ‘What about me, Miss? Write the book about me!’ So my novel THE DEVIL IN ERMINE is the events of 1483 from Buckingham’s point of view. I hope to have it up as an e-book very soon but there have been some hitches in getting the format right.

MISTRESS TO THE CROWNcame out in Australian shops in February and will be available soon in Germany and the U.K. I wanted to write about a woman who was at the heart of events in Yorkist England. Mistress Shore, King Edward’s lover, was perfect. No one had written a novel yet about the real Mistress Shore. Her name was Elizabeth Lambard and she was the daughter of a wealthy alderman, who was Sheriff of London and a supporter of the house of York.

More details about Ms Martyn’s latest book publication “Mistress to the Crown“:

Mistress to the Crown

- eHarlequin Australia

- U.K. edition coming in June 2013

- German edition announced for December 2013

About Jane Shore, mistress to King Edward IV’s and involved in an intrigue against King Richard III, and her struggle for freedom.

Isolde Martyn online:

www.isoldemartyn.com

Amazon.com-Author’s page

– RIII-articles from the year 2012 – complete list of the year 2011 –

Fifteenth-century remedies against witchcraft, part 2

***

Wishing those who marked these days — belatedly — a meaningful All Souls’ Day and Día de los muertos! I miss living more directly in the Mexican diaspora and hope that anyone who had access to one ate a piece of pan de muerto in my honor (picture at right; source).

Wishing those who marked these days — belatedly — a meaningful All Souls’ Day and Día de los muertos! I miss living more directly in the Mexican diaspora and hope that anyone who had access to one ate a piece of pan de muerto in my honor (picture at right; source).

***

Turning to England, I was alerted this morning that the BBC HistoryExtra currently offers a quiz to determine whether you would have been accused of witchcraft. It’s well-constructed, if a bit simplistic, and based on the information I gave, I would have been accused. (Hmmm. And it’s not because I’ve read the Malleus maleficarum repeatedly.) There’s also a podcast on the significance of the Plantagenets to British history, which I am downloading for later. Apropos of Plantagenets, Sharon Kay Penman noted, on her fan club facebook page (you must join to see), that today marks the anniversary of the birth of the ill-fated Edward V and his younger sister, Anne.

[Left: The surviving main building at the abbey of Cluny, where Abbot Odilo originated the celebration of All Souls’ Day in the early eleventh century. The spread of the celebration of this holiday is associated with growing belief in the doctrine of purgatory in the western church after the mid-tenth century. Source.]

[Left: The surviving main building at the abbey of Cluny, where Abbot Odilo originated the celebration of All Souls’ Day in the early eleventh century. The spread of the celebration of this holiday is associated with growing belief in the doctrine of purgatory in the western church after the mid-tenth century. Source.]

***

King Richard Magic Week continues below. Check out posts on the witchcraft’s threat to the crown in the fifteenth century, Gloucester’s witchcraft accusations in Richard III, and elite remedies against witchcraft.

***

Part II, question 2, ch. 6, of Malleus maleficarum, where exorcism to end bewitchment is discussed, is extraordinarily rich. A complete interpretation of it would explode the bounds of a single post. For instance, it treads perilously close to heresy several times — by proposing a remedy for witchcraft that is prohibited by canon law and was illegal in civil codes at the time in much of continental Europe (rebaptizing the victim); by charging that a priest in a state of grace is a more effective practitioner of an exorcism than a sinful one (a loophole may be that although the belief that a priest must be in a state of grace to perform a sacrament is heretical, exorcism is not a sacrament); and by suggesting that some baptisms were not effective the first time (clearly heretical because the sacraments work ex opere operato). But we’re interested in magic, not in heresy, here!

I noted in the previous post that the only remedy the Malleus maleficarum offers against witchcraft affecting the body is exorcism: the ritual or verbal casting out of demons or the Devil. In understanding the recommendations, it is helpful to consider what fifteenth-century authors might have meant by exorcism — since the common picture in the minds of most people today comes from an infamous 1971 film. (Maybe not so infamous to younger viewers — a review by a fellow Richard Armitage blogger expresses some confusion about the fame of the film.) And although the rank of “exorcist” was a minor order of the Church, it means something different now than it did in the 1470s. Indeed, the work stresses that one must not have taken the order in order to perform an exorcism.

Having thus discounted the possibility that exorcism differs from witchcraft because of the clerical status of its practitioner, the authors must set up a means by which an afflicted person can judge whether any exorcism would be lawful. They write:

The clergy have become too slothful to use any more the lawful words when they visit the sick. On this account … such lawful exorcisms may be used by a religious and discreet priest, or by a layman, or even by a woman of good life and proved discretion; by the offering of lawful prayers upon the sick. … And such persons are not to be prevented from practicing it in this way; unless perhaps it is feared that, following their example, other indiscreet persons should make improper use of incantations.

If the practitioner is pious, the victim may obtain help. The authors then list seven conditions for judging the lawfulness of remedies offered by such people: (1) no explicit or implicit invocation of devils; (2) no unknown names in charms; (3) nothing untrue in the words / no doggerel; (4) no written characters besides the sign of the cross — the authors note that this provision condemns most charms carried by soldiers; (5) no requirements regarding the method of writing or binding the charm on the person’s body; (6) use of scripture or words of saints must rely on effect from divine virtue or the relics of the saints; (7) the effect must be left open to divine will. “If none of these conditions be broken,” the authors conclude, “the incantation will be lawful.” These conditions established, the authors continue to note that a charm fixed around the neck is effective if the person who wears it understands the words in the charm; but if not, “it is enough if such a man fixes his thoughts on the divine virtue.”

If these simple measures have no effect, further steps can be taken. The afflicted person should make a good confession. Then, “let a diligent search be made in all corners and in the beds and mattresses and under the threshold of the door, in case some instrument of witchcraft may be found … and … all bedclothes and garments should be renewed, and … he should change his house and dwelling.” If these things do not avail, the afflicted should go the church on a feast day, take a holy candle, and pray. Various sacramentals (stole, holy water) should be employed. This ritual should be followed three times a week until successful. The victim should also receive the Eucharist, but only if he has not been excommunicated. Finally, the beginning words of the Gospel of John (“In the beginning was the Word …”) should be written and hung around his neck. (This widespread remedy against demonic attack in extremis is frequently evidenced in sources concerning women in childbirth, into the mid-sixteenth century.)

The authors then discuss reasons why exorcism — which is not a sacrament, so it doesn’t work automatically — may not work. Most of these relate to want of faith or piety in the victim, those praying for the victim or the exorcist, but the authors also suggest that the remedy may be flawed. Therefore the authors cite a final remedy for stubborn cases: rebaptism:

“It is said … of those who walk in their sleep during the night over high buildings without any harm, that it is the work of evil spirits who thus lead them; and many affirm that when such people are rebaptized they are much benefited. And it is wonderful that, when they are called by their own names, they suddenly fall to earth, as if that name had not been given to them in proper form at their baptism.”

Finally, the authors conclude with a discussion of natural remedies — which probably would have been the first resort of many people who sought to counter black magic with white. “If natural objects are used in a simple way to produce certain effects for which they are thought to have some natural virtue,” the authors conclude, “this is not unlawful. But if there are joined to this certain characters and unknown signs and vain observations, which manifestly cannot have any natural efficacy, then it is superstitious and unlawful.”

***

In the attempt to understand fifteenth-century piety and religion, we could make several observations about this body of remedies.

First, we’re clearly dealing with a mostly illiterate society here — so the shape of marks is more important than letters; and the remedies are claimed to work even if the victim is too uneducated to understand the sense of the words being used — which makes scriptural words hardly indistinguishable from magical marks, and one wonders how most people might have made the distinction.

Second, in contrast to the sort of universalizing statements the Latin church had regularly made about itself since at least the beginning of the thirteenth century, dealing with witchcraft gives the victim little reliance on the Church. After baptism, which includes a brief formula and prayer of exorcism (Exorcizo te, immunde spiritus, in nomine Patris + et Filii + et Spiritus + Sancti, ut exeas, et recedas ab hoc famulo …), the church has no additional tool to cast out the devil automatically, only a ritual (exorcism) that is dependent on the faith of the victim and those supporting him in his ordeal. Along the same lines, the authors suggest repeatedly that the clergy may not necessarily offer any help — they are too lazy, or not in a state of grace, or not pious enough. I tend not to be a big fan of the scholarly argument that Europeans on the eve of the Reformation were constantly tortured by the imminence of damnation and that medieval piety did nothing against such fears — but depending on how we understand it, this discussion of exorcism offers some anchoring for that position, even if the Reformation — which is only thirty years in the future at this point — clearly expanded both fears and persecutions of sorcery of various types.

Finally, and decisively, the remedies proposed look from our perspective suspiciously like witchcraft themselves in that they both explicitly legitimate the practice of witchcraft by giving it credibility (if you’re suffering, look for an enchanted object that’s causing it), and by suggesting mechanisms (charms, language, contact with relics) strongly similar to those used by witches to cause enchantments in the first place. Baptism is supposed to call demons out of the body of the baptizand — but the discussion if its efficacy implies that it also give the baptizand a name by which he may be called, putting him in a parallel position to beings, like demons and spirits, that may be summoned. The authors of the work seem unaware of or uninterested in this relationship, a parallelism that suggests that they themselves were incorporated into the paradigm that made witchcraft accusations simply “make sense” in explaining the world.

***

And Shakespeare’s Gloucester? He could have undertaken any of these things — but, the implication is, he himself is so implicated in the disordered and unlawful relationships exemplified by witchcraft that he choose to wreak further havoc rather than dealing with them.

***

Calendar-wise, Magic Week 2012 is over, but I had two more subjects planned for this series. I will try to get to them this week. I’m also happy to answer questions if anything’s unclear.

Protecting Richard: Fifteenth-century remedies against witchcraft, part 1

***

King Richard Magic Week 2012 continues! I apologize for not posting on Halloween — Wednesday is a big teaching / office / service day for me. Happy Samhain to those who celebrated it and Happy All Saints’ Day to those celebrating that.

***

In the first post in this series, on the reality of witchcraft threats in early modern England, I argued that discussions of witchcraft need to be taken seriously on their own terms (as opposed to being understood as a symptom or reflection of something else). In the second post, on Gloucester’s witchcraft accusations in Shakespeare’s Richard III, I argued, given that Shakespeare can be assumed to share the beliefs of his age, Gloucester’s use of the witchcraft accusation against Elizabeth and Jane Shore is a way for the characters in the play and its audiences to account for the disorder of a political world in which Gloucester could accuse Hastings, historically one of his family’s most loyal supporters, with treason. Following on those two posts, given that witchcraft was real for Richard III’s contemporaries and that it was a factor for a century later in explaining the ills of politics gone wrong, as another means of talking about fifteenth-century ideas, I want to ask a hypothetical counterfactual. Assuming that Richard III had been beset by witchcraft, how could he have cured this situation?

In the first post in this series, on the reality of witchcraft threats in early modern England, I argued that discussions of witchcraft need to be taken seriously on their own terms (as opposed to being understood as a symptom or reflection of something else). In the second post, on Gloucester’s witchcraft accusations in Shakespeare’s Richard III, I argued, given that Shakespeare can be assumed to share the beliefs of his age, Gloucester’s use of the witchcraft accusation against Elizabeth and Jane Shore is a way for the characters in the play and its audiences to account for the disorder of a political world in which Gloucester could accuse Hastings, historically one of his family’s most loyal supporters, with treason. Following on those two posts, given that witchcraft was real for Richard III’s contemporaries and that it was a factor for a century later in explaining the ills of politics gone wrong, as another means of talking about fifteenth-century ideas, I want to ask a hypothetical counterfactual. Assuming that Richard III had been beset by witchcraft, how could he have cured this situation?

[Right: Canon episcopi in Hs. 119 (Cologne), a ninth-century passage in canon law on witchcraft beliefs. Source.]

***

Were we able to juxtapose Richard and Shakespeare, we would likely discover that Shakespeare, writing around 1591, was probably significantly more knowledgeable about witchcraft than Richard, who died over a century earlier, would have been. Richard lived in a watershed period for explaining and understanding witchcraft. Medieval monarchs and churchmen alike had been negative to skeptical about popular beliefs about the efficacy of witchcraft, which they associated with paganism, until approximately the mid-thirteenth century. Indeed, this skepticism had been incorporated into canon law via the text of Canon episocopi, a text that argued that people who believed in efficacious witchcraft were heretics who had lost their faith and succumbed to the Devil. The effects of witchcraft occurred in the imagination, not in physical reality.

The text of this document points implicitly to an “incomplete” Christianization of Europe before the Reformation — an possibility substantiated in historical works by scholars like Jean Delumeau, especially Le Catholicisme entre Luther et Voltaire (1971). Many pre-Christian beliefs and traditions persisted in the popular Latin Christianity of the fifteenth-century, some of which were shared in elite populations as well. Most English people maintained some belief in both white magic and its opposite, maleficium (which we usually translate, a bit loosely, as sorcery), and many might have taken resort in popular magic as a way of dealing with their world through charms, potions, or amulets, but trials for maleficium were rare and punishments for the convicted remained light throughout the Middle Ages.

The text of this document points implicitly to an “incomplete” Christianization of Europe before the Reformation — an possibility substantiated in historical works by scholars like Jean Delumeau, especially Le Catholicisme entre Luther et Voltaire (1971). Many pre-Christian beliefs and traditions persisted in the popular Latin Christianity of the fifteenth-century, some of which were shared in elite populations as well. Most English people maintained some belief in both white magic and its opposite, maleficium (which we usually translate, a bit loosely, as sorcery), and many might have taken resort in popular magic as a way of dealing with their world through charms, potions, or amulets, but trials for maleficium were rare and punishments for the convicted remained light throughout the Middle Ages.

***

[Right: Title page of Nider’s Formicarius (this edition, Cologne 1506), a copy that belonged at some point to a monastery, made its way to the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, and has now been digitalized. Source of image — follow the link and you can page through the book.]

***

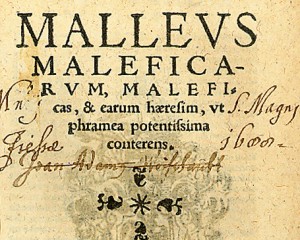

This state of affairs was changing after the mid-thirteenth century, a point at which heresy prosecutions in general were on the rise, and reached a critical point in the fifteenth century, as growth of learned knowledge about the supernatural world caused educated men to seek out evidence of their discoveries in the world around them. Traditions of elite magic grew and intensified among clerics, and as they did, scholars sought to connect these to popular practices. (We’ll look at elite magic — more closely associated with wands than the popular traditions that preceded the fifteenth century — in one of the final posts in this series.) Two learned works of the fifteenth century, Johannes Nider’s Formicarius and Heinrich Sprenger’s Malleus maleficarum, played important roles in convincing learned men to turn against the late medieval consensus, arguing that witchcraft was not a delusion on the part of the observer, but real and efficacious. Nider’s work, written in the 1430s but first published in 1475, was the first to argue that the true threat of witchcraft came not from elite necromancers, but from uneducated females; Malleus maleficarum (1486) argued that witchcraft or belief in its effects were not delusions that reflected the loss of faith on the part of the believer, but rather actually occurring activities with real effects conducted by people who had consciously allied with the Devil for this purpose.

[Left: Section of title page of Malleus maleficarum (edition of Cologne 1520. This one’s in Sydney, Australia. Source.]

***

In reading these works, of course, it’s important to keep in mind that at the time of their publication, they were prescriptive rather than descriptive. Nider had to convince his audience that female witches were a greater threat than learned male magicians; Malleus maleficarum attempts to persuade clergymen and other authorities to look for evidence of maleficium in the world around them and act against it rather than turning a blind eye. These authors were less recounting a popular attitude than trying to prescribe what it should be; nonetheless, their influence means that by the time Shakespeare was writing, in any case, elements of their worldview were generally shared by elite and popular minds alike. In Part II, question 2, ch. 3, Malleus describes “inflammation with inordinate love” as “the best known and most general form of witchcraft.” So Edward IV could have been bewitched by Elizabeth Woodville — as the authors of Titulus Regius had argued he was. In Part II, question 1, ch. 5, Malleus states that witches have six ways of harming humans, among them “to cause some disease in any of the human organs … to take away life.” So Richard’s injuries as he describes them could have been caused by witchcraft.

What would an expert have told him to do? Malleus maleficarum does not leave the reader alone with the problem of maleficium. It recommends remedies; interestingly, in doing so, by distinguishing between lawful and unlawful ones, it gives us a sense of the entire range of things that people might have been inclined to do. The first thing the afflicted should not do is resort to a counter-maleficium of any kind, an index to the authors’ fear that this is the first thought someone might have. Because the authors argue throughout that sorcery is real, they must concede that such remedies could be effective — but in their association with the Devil, they were not permitted to Christians. On the matter of responding to inordinate love, Malleus notes that some of it is not due to witchcraft, and that ancient authors offered varying suggestions for dealing with it but then asks, “what use is it to speak of remedies to those who desire no remedy?” (P. II, q. 2, ch. 3). (I daresay that was Edward’s problem.) In the main, however, it suggests five remedies (P. II, q.2, ch. 2): “a pilgrimage to some holy and venerable shrine; true confession of sins with contrition; the plentiful use of the sign of the Cross and devout prayer; lawful exorcism by solemn words … and … a remedy can be affected by prudently approaching the witch.” In recommending that the victim simply ask the witch to stop, Malleus again concedes the primacy of the supernatural and the possibility that maleficium could win out if not opposed.

What would an expert have told him to do? Malleus maleficarum does not leave the reader alone with the problem of maleficium. It recommends remedies; interestingly, in doing so, by distinguishing between lawful and unlawful ones, it gives us a sense of the entire range of things that people might have been inclined to do. The first thing the afflicted should not do is resort to a counter-maleficium of any kind, an index to the authors’ fear that this is the first thought someone might have. Because the authors argue throughout that sorcery is real, they must concede that such remedies could be effective — but in their association with the Devil, they were not permitted to Christians. On the matter of responding to inordinate love, Malleus notes that some of it is not due to witchcraft, and that ancient authors offered varying suggestions for dealing with it but then asks, “what use is it to speak of remedies to those who desire no remedy?” (P. II, q. 2, ch. 3). (I daresay that was Edward’s problem.) In the main, however, it suggests five remedies (P. II, q.2, ch. 2): “a pilgrimage to some holy and venerable shrine; true confession of sins with contrition; the plentiful use of the sign of the Cross and devout prayer; lawful exorcism by solemn words … and … a remedy can be affected by prudently approaching the witch.” In recommending that the victim simply ask the witch to stop, Malleus again concedes the primacy of the supernatural and the possibility that maleficium could win out if not opposed.

***

When reading these sources, I’m always tempted to wonder whether the authors considered the possibility that in their remedies to witchcraft, they had embraced exactly the position they had hoped to eradicate. On the question of Richard’s arm, the solutions proposed by Malleus (P. II, q. 2, ch. 6) are rather more severe: only an exorcism will do. Because the procedure described is rather complicated, I’ll take up that topic on in the next post. However, I’ll leave you with a cliffhanger: in discussing the definition of an exorcist, the authors of Malleus call exorcists “lawful enchanters.” Thus, the remedies we can expect to have recommended bear a startling resemblance to the ills that caused them — a resemblance that the authors themselves concede.

***

If you’re interested, Malleus maleficarum is easy to obtain in modern translation; it’s both readable and gruesomely entertaining. The most widely available English translation, published by Montague Summers, is at best serviceable — Summers was a charlatan and the notes and ‘scholarly apparatus’ attached his editions are a mixture of uselessness and nonsense. A better translation with the most up-to-date approach to the scholarship — the one I make my students use — is Christopher Mackay’s Hammer of Witches (2009).

If you’re interested, Malleus maleficarum is easy to obtain in modern translation; it’s both readable and gruesomely entertaining. The most widely available English translation, published by Montague Summers, is at best serviceable — Summers was a charlatan and the notes and ‘scholarly apparatus’ attached his editions are a mixture of uselessness and nonsense. A better translation with the most up-to-date approach to the scholarship — the one I make my students use — is Christopher Mackay’s Hammer of Witches (2009).

“See how I am bewitch’d”: Interpreting witchcraft accusations in Shakespeare’s “Richard III’

***

King Richard’s Magic Week 2012 continues. The first post, on the significance of magic in the fifteenth century, is found here. My reading tip — if you want to plumb current scholarly understandings of what magic and witchcraft meant in the early modern context — and you’re not afraid of exposing yourself to some serious erudition — the book’s been described as “evocative and relentlessly academic” but also as “unrivalled” — I can make no more compelling recommendation than Stuart Clark’s Thinking with Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe (1999), upon which many of my insights and arguments about the intertwining of various strands of early modern life with witchcraft are drawn. I love this book; my copy is battered and worn.

In this post, I draw on Clark’s idea that witchcraft accusations were not a pretext for political moves, but rather understood by early modern people as an intimate factor in how politics actually worked.

***

In Act III, scene iv of Shakespeare’s Richard III, in an intriguing exchange, the character of Gloucester (Richard’s title before becoming king) attributes his physical deformity to the machinations of witches — specifically, his late brother Edward’s wife and Edward’s mistress, Jane Shore. After charging that they have sought his death with their “devilish plots,” he urges:

Then be your eyes the witness of this ill:

See how I am bewitch’d; behold mine arm

Is, like a blasted sapling, wither’d up:

And this is Edward’s wife, that monstrous witch,

Consorted with that harlot strumpet Shore,

That by their witchcraft thus have marked me.

Laying aside Shakespeare’s bias against Richard, as well as the debates over the status of his physique — although the language and image of a “blasted sapling” are compelling to me — the modern reader is likely to interpret this accusation as a political or misogynistic pretext for Richard’s rapaciousness. Such a reading seems at first to be supported by Gloucester’s declaration, in subsequent lines, that if Hastings is not willing to agree to this explanation, he must be a traitor:

“If! Thou protector of this damned strumpet–

Tellest thou me of ‘ifs’? Thou art a traitor:

Off with his head!”

Gloucester appears, here, to accuse the women of witchcraft as an excuse to eliminate anyone who disagrees with his usurping power grab.

Hastings’ intermediate line, however, tends to balance this reading with evidence of a worldview that attributed misfortunes to supernatural influences; Hastings does not say, “there are no witches,” or “witches don’t do things like that,” or even, “don’t accuse these women of being witches,” but rather, “If they have done this thing […] –” a line that explicitly concedes that witches exist who accomplish such deeds, though Gloucester cuts Hastings off, and we don’t get a “then” from him. This interpretation gains more currency when we consider that Shakespeare lacked access to Titulus Regius, the document that formulated the charge of witchcraft against Woodville and her mother — Henry VII had ordered all copies of it in English archives destroyed in order to protect his wife against the claims of illegitimacy that had justified the deposition of her younger brother, and our modern awareness of it postdates Richard III — and must have had another source, which points to a cultural willingness to associate Woodville with witchcraft. Finally, when we think about this scene in the context of political history, we note that the elimination of Hastings — who was supposed to have been in league with Elizabeth Woodville to keep her son, Edward V, on the throne, with the infamous Shore, also his mistress, as go-between for the conspirators — constituted a key step in Richard’s move toward the throne. But Hastings had made important sacrifices for the York family in the past, going into exile with Edward and Richard, and supporting Richard’s role as Lord Protector against the Woodvilles. In light of these political circumstances, of which the playwright was certainly aware, I suggest that Shakespeare does not have Gloucester accuse the women of witchcraft in order to present him as scheming to achieve his ends. Rather, Gloucester’s accusation in the play reflects his conviction that if something is troubling in his body or his political circumstances, then there must be an explanation — witches.

Hastings’ intermediate line, however, tends to balance this reading with evidence of a worldview that attributed misfortunes to supernatural influences; Hastings does not say, “there are no witches,” or “witches don’t do things like that,” or even, “don’t accuse these women of being witches,” but rather, “If they have done this thing […] –” a line that explicitly concedes that witches exist who accomplish such deeds, though Gloucester cuts Hastings off, and we don’t get a “then” from him. This interpretation gains more currency when we consider that Shakespeare lacked access to Titulus Regius, the document that formulated the charge of witchcraft against Woodville and her mother — Henry VII had ordered all copies of it in English archives destroyed in order to protect his wife against the claims of illegitimacy that had justified the deposition of her younger brother, and our modern awareness of it postdates Richard III — and must have had another source, which points to a cultural willingness to associate Woodville with witchcraft. Finally, when we think about this scene in the context of political history, we note that the elimination of Hastings — who was supposed to have been in league with Elizabeth Woodville to keep her son, Edward V, on the throne, with the infamous Shore, also his mistress, as go-between for the conspirators — constituted a key step in Richard’s move toward the throne. But Hastings had made important sacrifices for the York family in the past, going into exile with Edward and Richard, and supporting Richard’s role as Lord Protector against the Woodvilles. In light of these political circumstances, of which the playwright was certainly aware, I suggest that Shakespeare does not have Gloucester accuse the women of witchcraft in order to present him as scheming to achieve his ends. Rather, Gloucester’s accusation in the play reflects his conviction that if something is troubling in his body or his political circumstances, then there must be an explanation — witches.

Applying Clark to Shakespeare generates the following possible reading: One of the most common perversions associated with sorcery in the period was the distortion of love — and Richard should have loved Hastings. And yet he does not — which suggests something larger in the world of the play is amiss. While it’s clear that Shakespeare doesn’t much like Gloucester, this scene suggests that Gloucester is not so much evil because he lies — rather, he lies because everything around him, from his body to his ambitions, is permeated with demonic influences. In response, Richard, who reveals here that he’s quite conscious of this state of affairs, does not react against the influence of witches, but indeed cooperates with it. Richard, for Shakespeare, is thus much more than simply a usurper and a schemer — his usurpation and schemes are symptomatic of a political world gone wrong under the influence of supernatural forces.

Applying Clark to Shakespeare generates the following possible reading: One of the most common perversions associated with sorcery in the period was the distortion of love — and Richard should have loved Hastings. And yet he does not — which suggests something larger in the world of the play is amiss. While it’s clear that Shakespeare doesn’t much like Gloucester, this scene suggests that Gloucester is not so much evil because he lies — rather, he lies because everything around him, from his body to his ambitions, is permeated with demonic influences. In response, Richard, who reveals here that he’s quite conscious of this state of affairs, does not react against the influence of witches, but indeed cooperates with it. Richard, for Shakespeare, is thus much more than simply a usurper and a schemer — his usurpation and schemes are symptomatic of a political world gone wrong under the influence of supernatural forces.

***

Could he have reacted against demonic influence? Had Richard’s political and personal ends been fouled by witchcraft, could he have done anything about it? Yes, indeed — he could have. Seeing as how this is getting long, again, however, I’ll go to that theme in my next post, which will concern recommended fifteenth-century remedies against witchcraft.

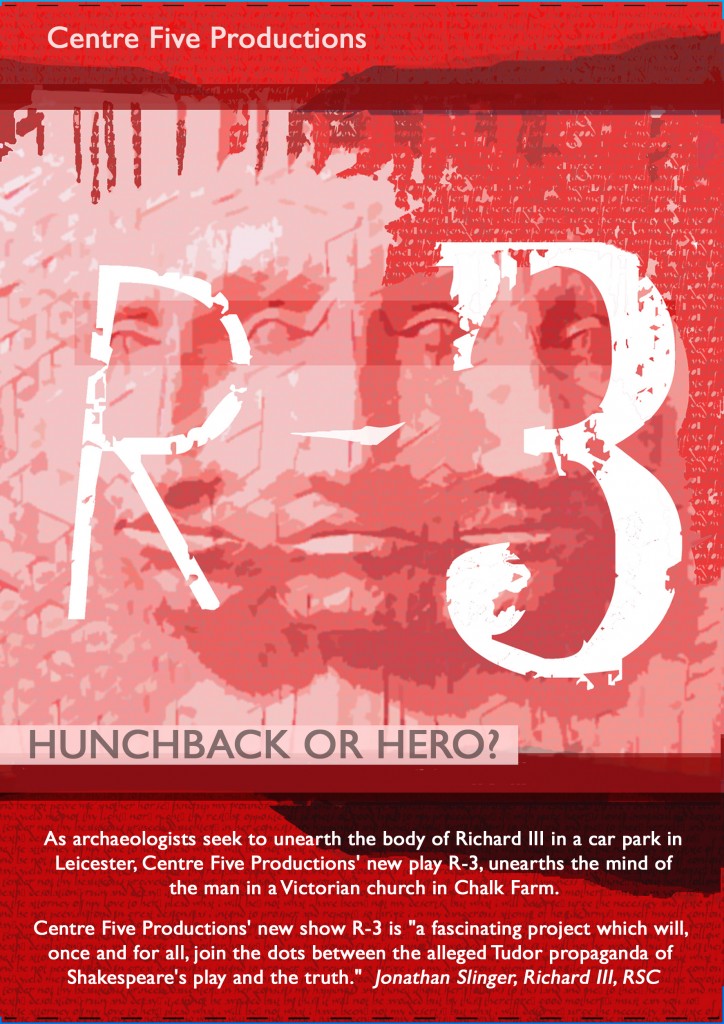

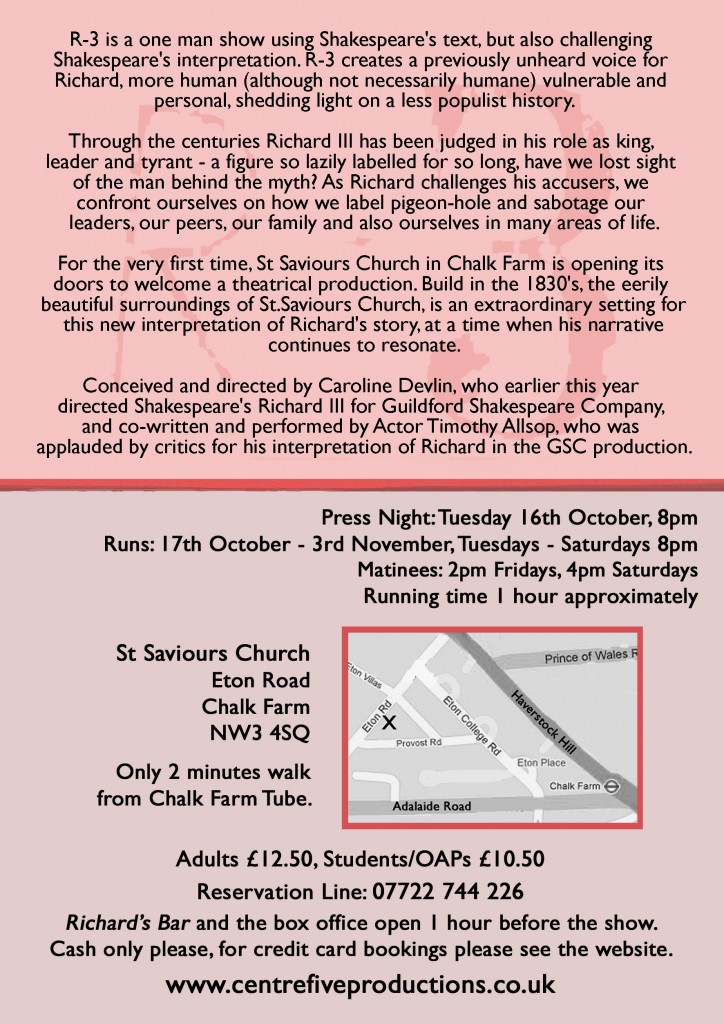

Is Shakespeare Altering His View of “R-3” ?

Today:

♛ R-3 Play ♛

For a long time, Shakespeare’s “Richard III” has dominated the perception of King Richard III.

Now, with modern research, we have more details about the king and can get closer to the true story. Soon the results of the mtDNA research are expected, but what does this all mean about how we see the king?

A new play by Caroline Devlin, “R-3”, is about Shakespeare’s play, but heavily influenced by the research by historian Dr. John Ashdown-Hill, who had a major influence on the research, location as well as on finding the reference person for the mtDNA comparison, Mr. Michael Ibsen.

The play asks the fundamental question about King Richard III:

Hunchback or Hero?

R-3

created by

Caroline Devlin and Timothy Allsop

(Centre Five Productions)

Running from

17 October – 3 November 2012

at St. Saviour’s Church, London

(Eton Road, NW3 4SQ,

2 min walk from Chalk Farm Tube)

Further information & reservation:

www.centrefiveproductions.co.uk

♛ Leicester News ♛

- “Richard III Leicester” is a new Facebook page with current updates and news about King Richard III by the City Council of Leicester, which is one of the participants, financiers and initiators of the archaeological research in Leicester.

- Richard III dig: Is there millions in Shakespeare’s villain? – Video report about the monetary aspect of finding a king under a carpark. – BBC News Leicester, 15.10.12

- Richard III archaeology team awarded honour for Leicester dig – Report about an award, Philippa Langley received from the Richard III Society for her wonderful work for King Richard III. (ThisIsLeicestershire.co.uk, 15.10.12)

- Many say Richard for York – The battle for King Richard III has just begun, (Leicester Mercury, ThisIsLeicestershire.co.uk, 12.10.2012)

- Possible Richard III discovery could hold success for economy of Hinckley and Bosworth – The Hinckley Times, Katy Hallam (11.10.12)

♛ Collective Reading ♛

Servetus has the leading questions to the chapters 6 – 10 of “The Sunne in Splendour” by Sharon Kay Penman and a poll for you:

Are you ready for the Richard III rumble? Week 2!

Servetus’ background information and new questions to chapter 11 – 15: Richard III / The Sunne in Splendour group read rumbles on! Week 3

Chapters 16 – 20 are on the reading list for this week and will be discussed next Sunday, October 21st, 2012.

Important Links for the read:

(Under development)

If you want to join in and still need a copy of the book, please consider to make your purchase via the link at RichardArmitageNet.com, where reference fees will go to the charities selected by Mr. Armitage. Thank you!

Amazon.co.uk – Amazon.com Print & Kindle edition

Reference fees gained through links at the KRA website also go to the RA-charities.

In Dear Memory – George Peter Algar

Today, the very sad news reached us that our supporter and presented author

George Peter Algar

died last Thursday.

We very much mourn the loss of such a wonderful person and inspiring contact.

Though we only briefly knew him and never met in person, we will greatly miss his friendly and openly helpful approach and creative ideas.

He supported us with an interview, details about his book “The Shepherd Lord“, by bringing us in contact with the Towton Battlefield Society and just with a wonderful and openminded mail correspondence.

Riikka Nikko, his contact and King Richard III artist from Finland, gave us permission to post her creation in memory of Mr. Algar. The work progressed with input by Mr. Algar.

The merciful and avenging angel King Richard, by Riikka Nikko (More details about her and her King Richard creations can be found in her artwork-portfolio and in this KRA-article):

What a hopeful image of the world that awaits us, entirely under the protection of King Richard III.